The Magazine ANTIQUES | February 2009

Walker Evans believed in picture postcards. The great photographer began collecting them as a boy, years before he ever snapped his first picture. Throughout his life he celebrated them, wrote about them, experimented with the format, and continued to collect them. “On their tinted surfaces,” he wrote in a 1948 Fortune magazine article, “were some of the truest visual records ever made of any period.”1

The more than nine thousand cards he collected from childhood until his death in 1975 at the age of seventy-one—most of them produced in the first decades of the twentieth century—now reside with the rest of his archives at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Walker Evans and the Picture Postcard, an exhibition based on the collection on view at the museum from February 3 to May 25, examines the connection between the art of a renowned photographer and the anonymous works that inspired his lifelong fascination. Some three hundred of the cards are on display, along with a small selection of related photographs by Evans.

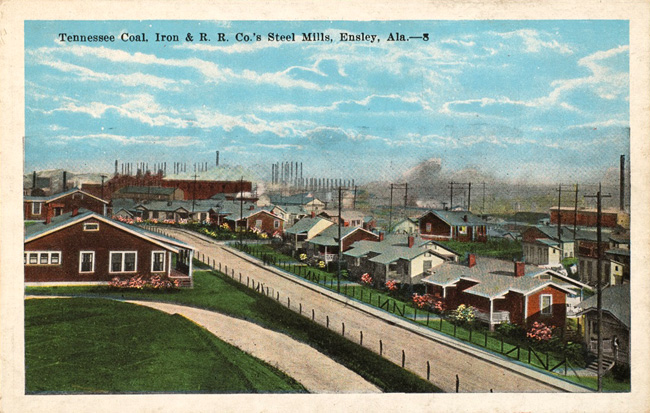

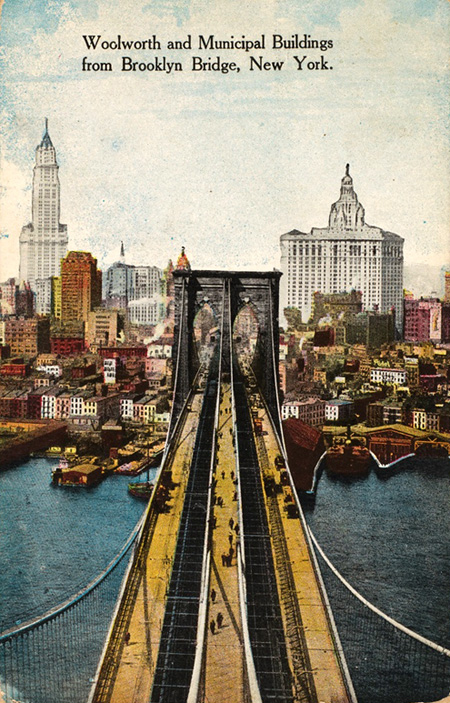

If you have even a vague familiarity with Evans’s work, the connection seems obvious. Picture postcards, especially those from the early period of Evans’s collection, are quintessentially matter of fact. Nobody tried too hard to make them pretty. They show buildings that are, as Evans said, “extraordinarily unbeautiful,” streets clogged with traffic, and factories belching smoke.2 You do not doubt for a minute that this is what things looked like.

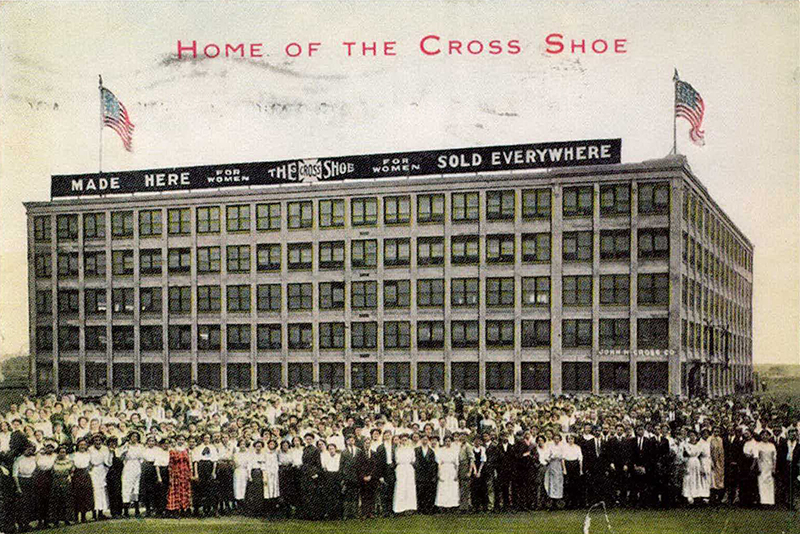

Take for example a postcard of a shoe factory in western Massachusetts (Fig. 7). The card shows a large, unlovely five-story building head on in its entirety. Posed in front of the factory are a hundred or more of its workers. You want to look closely enough to figure out who kept the books and who affixed the soles, but everyone is looking his or her best so it is hard to tell. Centered at the top of the building’s facade are the words “The Cross Shoe,” flanked by the phrases “Made Here” and “Sold Everywhere.” Like many of the cards Evans collected, it expresses pride in an ordinary, even ugly, place. And like some of Evans’s photographs, the image implies a whole social and economic order. Certainly, the big sign recalls those that dominate some of his most famous images.

If you look at many Evans photographs after looking at the postcards, they have this same matter of factness, but somehow intensified. The postcards seem artlessly honest while Evans’s images are clearly works of art and thus, inevitably, more manipulated, and more emotionally gripping. But if you trust what he shows, it is, at least in part, because he learned the language of postcards. “Even the titles Evans gave his photographs sound like those found on postcards,” says Jeff L. Rosenheim, the curator in the Metropolitan Museum’s Department of Photographs who organized the show. “They show simplicity, but absolute specificity of description.”

Rosenheim, who also curated the museum’s 2000 retrospective of Evans’s work, is quick to point out that this show is as much, if not more, about postcards as it is about Evans. “Postcards are a democratic form. They are about everywhere in particular. And there was no nostalgia about them. They show the new banks, the new factory, the new school. They were a clear expression of the present.”

Evans was born in 1903 into the golden age of postcards. It began in 1901 when the post office allowed private companies to print picture postcards that could be mailed using a one-cent stamp. At first only the address could be written on the back of the card, but in 1907 the rules were changed and there was space for people to write their two-cents’ worth. What had been a fad became a mania, as the number of postcards sent in the United States began to approach nearly a billion a year. Since most of the cards were produced in Germany, World War I brought an end to the postcard craze.

“In the 1900’s, sending and saving picture postcards was a prevalent and often a deadly boring fad in the million middle class homes,” Evans wrote, greatly understating the cards’ popularity. “Yet the plethora of cards printed in that period now forms a solid bank from which to draw some of the most charming and, on occasion, the most horrid mementos ever bequeathed one generation by another.”3 Boring or not, Evans partook of the fad, and for the rest of his life collected the cards produced when he was a boy.

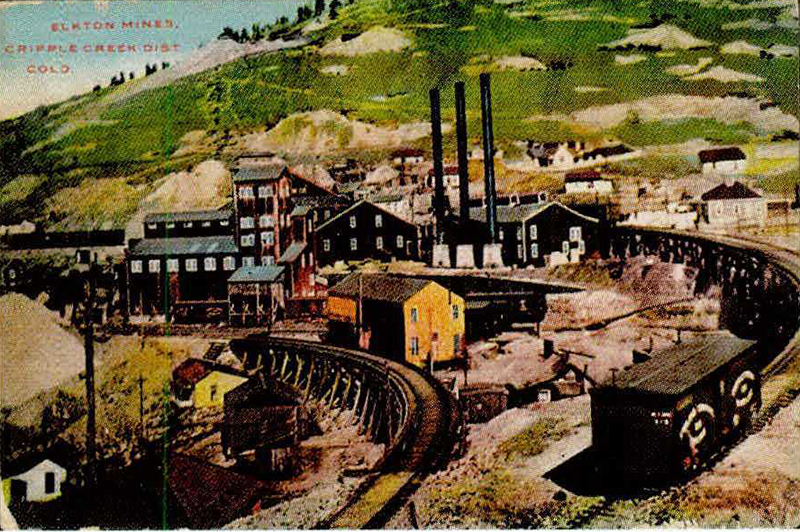

“The picture postcard is a folk document,” he declared in 1962, in an article praising “these honest and direct little pictures.”4 Their production however was hardly local and folkish, but rather part of a multinational industry. The basic images were shot in black and white by mostly anonymous local photographers. They were then sent to Germany where color was added, most likely by people who had never seen the locales whose color they sought to evoke. They liked to add florid sunsets and blue skies with great puffy clouds, but the subjects themselves tended to be treated in a way that is understated and restrained, very different from the later garish cards based on color photographs. Still, there was artifice. One of the cards Evans showed in Fortune and in his lectures is of Elkton Mines, in Cripple Creek, Colorado (Fig. 2). It depicts a hillside with a cluster of utilitarian buildings. The thing that makes it memorable is a building with a gable tinted a bright gold color. This vivid touch changes one’s view of the composition; you see the abstract forms hidden in the hasty, haphazard workaday construction. And it does remind us that we are looking at a gold mine. This may be a true picture, but it is hardly a neutral document.

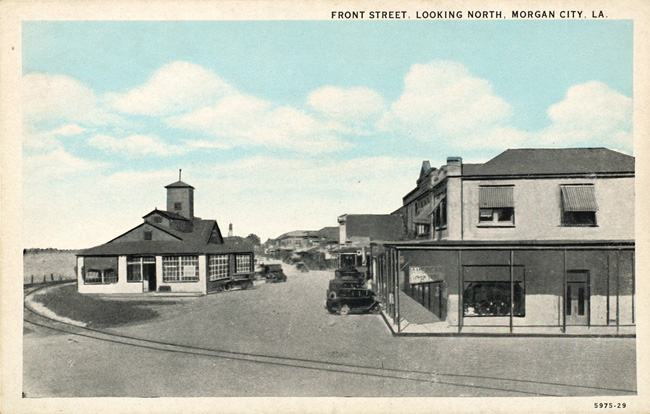

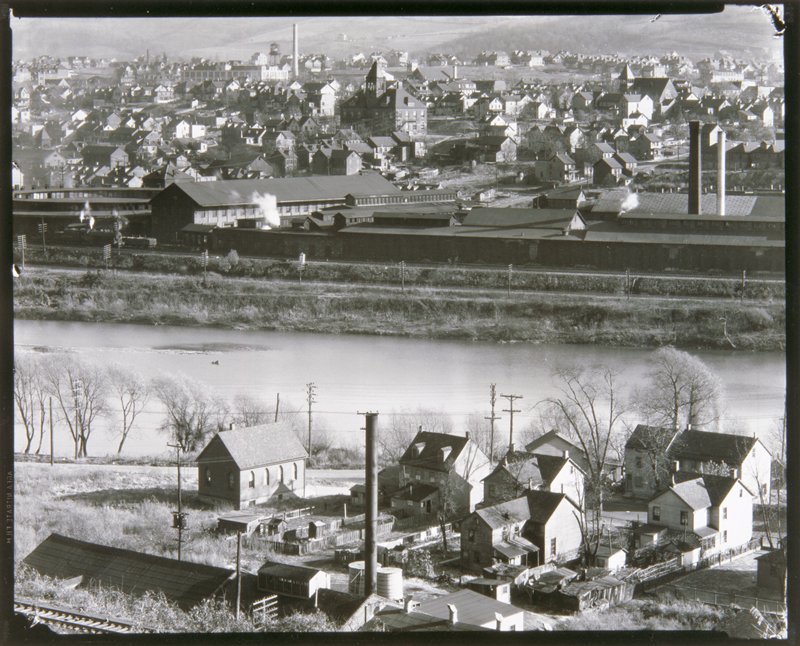

One of Evans’s works in the show spotlights the issue of reality and artifice in postcard imagery. His 1935 photograph Main Street, from Across Railroad Tracks, Morgan City, Louisiana (Fig. 6) is almost identical to a postcard copyrighted in 1929 in his collection (Fig. 5). Evans and the anonymous photographer of the postcard must have stood in precisely the same place, but the nameless shooter got there first. The only difference between the two images is that on the postcard the sky is tinted a brilliant blue with puffy clouds, and more significantly, all the utility poles and wires are missing.

Evans liked these seemingly intrusive and chaotic elements of the modernizing city. In 1948 he celebrated their visibility in cards he had collected: “These precisely are the downtown telegraph poles fretting the sky, looped and threaded from High Street to the depot and back again, humming of deaths and transactions.”5 “‘Downtown’ was a beautiful mess,” he wrote in 1962. “The tangle of telephone poles and wires attests to that.”6

It is likely that the poles and wires were removed from the Morgan City postcard for aesthetic reasons, but did Evans take his picture simply to get them back in? Many of the postcards in his collection have been cut down to remove borders and strengthen the composition; he clearly was not hesitant to improve the cards, though this would be an extreme example.

Rosenheim, for his part, is baffled. “Why did he go to Morgan City?” he muses. “Did he go because of the postcard? Where would you find a postcard of a town with 750 people in it?” And if he happened to be in Morgan City, found the postcard and decided to take exactly the same picture, it may well be the only time he did such a thing. We will probably never know, and we will probably never care quite as much as Rosenheim does. Still, despite Evans’s celebration of the documentary value of postcards, in this case the artist’s version gives a truer, messier account of the way things were.

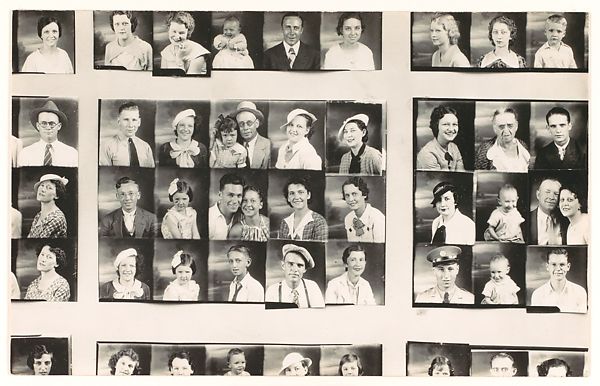

Most of the exhibition consists of postcards from Evans’s collection, which he categorized by such subjects as “courthouses,” “boats,” and Rosenheim’s favorite, “architecture-ordinary.” In 1936, however, he purchased some postcard stock, preprinted on the back with a place for the address and a stamp, and printed his own postcards, about a dozen of which are in the show (see Figs. 8, 11). These look nothing like the other cards on view. Indeed, most of Evans’s photographs look more like postcards than these do. The ones he printed on postcard stock are not local, specific, or informative. Rather, they are abstract, and a bit arty.

The artiness springs from the way in which they were made. Evans used a camera that produced eight-by-ten-inch negatives. To make his postcards, he simply contact printed part of his negative onto the smaller format paper. For example, a negative that showed a cluster of buildings, weighty and complete, yielded a postcard of gables and rooflines (see Figs. 8, 9). It takes a moment to realize that the abstract composition was hiding—at exactly the same size—in the larger image all along.

Evans kept his postcards in file boxes inside leather suitcases, with tabs that showed his slightly inconsistent filing system. Often, Rosenheim says, the same card turns up in several different categories. This makes sense because the same image can show many different things, and Evans used the postcards as tools to help himself see.

Evans was a connoisseur of the throwaway, and his other collections at the Metropolitan Museum include holdings of crushed tin cans, medicine labels, and driftwood. When he was teaching at Yale during the last decade of his life, Rosenheim said, he would walk on the beach with students and discuss why one piece of driftwood was worth looking at and another was not. “It was all about exercising the eye.”

The postcards, though, afford the deepest and most engaging exploration of how an artist saw his world. “My ultimate ambition for the show,” Rosenheim says, “would be that people would see the postcards and Evans’s responses to them, and then go out into the street with fresh eyes, aware of the beauties of the commonplace.”

1 Walker Evans, “Main Street Looking North from Courthouse Square,” Fortune, vol. 37 (May 1948), p. 102. 2 Evans, “When ‘Downtown’ Was a Beautiful Mess,” ibid., vol. 65 (January 1962), p. 101. 3 Evans, “Main Street Looking North from Courthouse Square,” p. 102. 4 Evans, “When ‘Downtown’ Was a Beautiful Mess,” p. 101. 5 Evans, “Main Street Looking North from Courthouse Square,” p. 102. 6 Evans, “When ‘Downtown’ Was a Beautiful Mess,” p. 101.

THOMAS HINE is the author of six books including Populuxe and The Great Funk: Styles of the Shaggy, Sexy, Shameless 1970s, to be published in paperback by Farrar Straus Giroux in February.