The Magazine ANTIQUES | December 2008

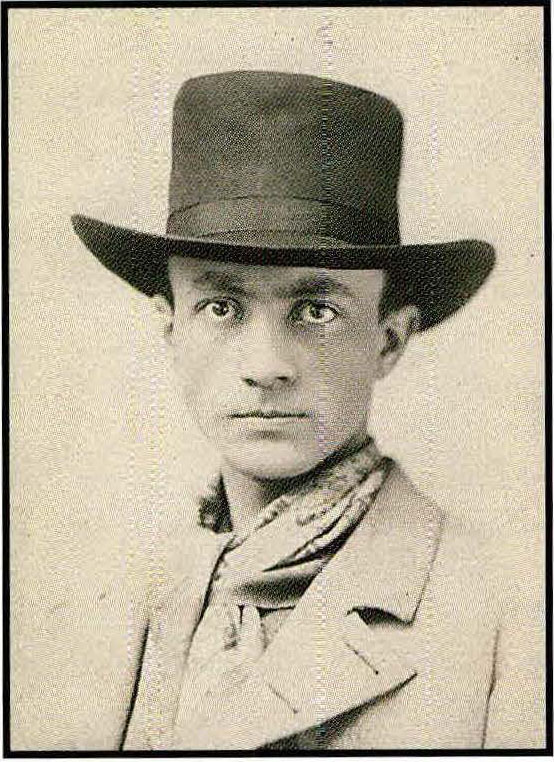

Charles and Ray Eames, Russel and Mary Wright, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret Macdonald—the artistic collaboration of such husband and wife teams is now understood as an important aspect of twentieth-century design. In some of these joint enterprises, the wives functioned as administrators or business women; in others the collaborative endeavor was considerably more artistic. For the furniture designer Charles Rohlfs (Fig. 3) and his wife, Anna Katharine Green (Fig. 1), the intermeshing of theater and literature, design and the home, and art and life was the defining characteristic of their marriage.

One of the most enigmatic and celebrated American designers of the early twentieth century, Rohlfs is today represented in leading museum collections around the country. Despite his fame, however, the role of Green, better known as a successful mystery novelist of the late nineteenth century, as his first and only design collaborator has been virtually unknown to curators and scholars of decorative art until recently. In this article I will present information about Green’s life and art gleaned from the Rohlfs family papers, many of which were recently donated by their great-granddaughter to the Winterthur Library. I will also analyze a number of decorative works by Rohlfs and Green that have never been fully documented. This examination will be founded on detailed background information on the crucial moment, around 1888, when they first created furnishings for their own use.

Rohlfs married Green on November 25, 1884, at the South Congregational Church in Brooklyn, New York. In the midst of their mutual successes over the next several years—Green’s flurry of publishing and Rohlfs’s achievements in acting and industrial design—on July 29, 1887, the couple and their children (twenty-three-month-old Rosamond and newborn Sterling) moved upstate to Buffalo. Rohlfs’s work in industrial design had yielded him a number of patents for stove designs and a job offer in the “Queen City of the Great Lakes” from Sherman S. Jewett and Company. Buffalo was to be their home for the next forty-five years. Here they continued earlier efforts to design and make furniture for themselves that was appropriate to their artistic taste.

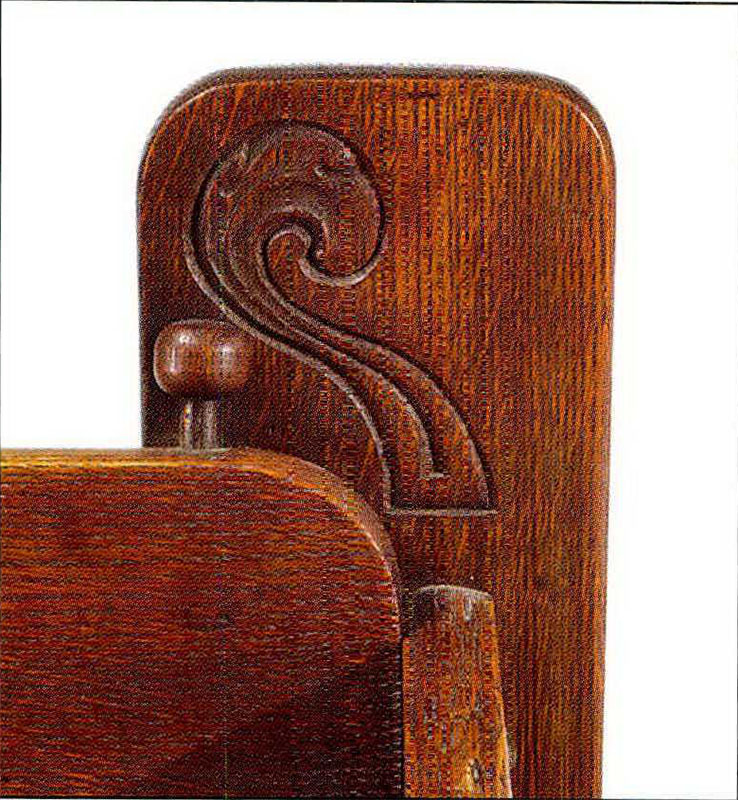

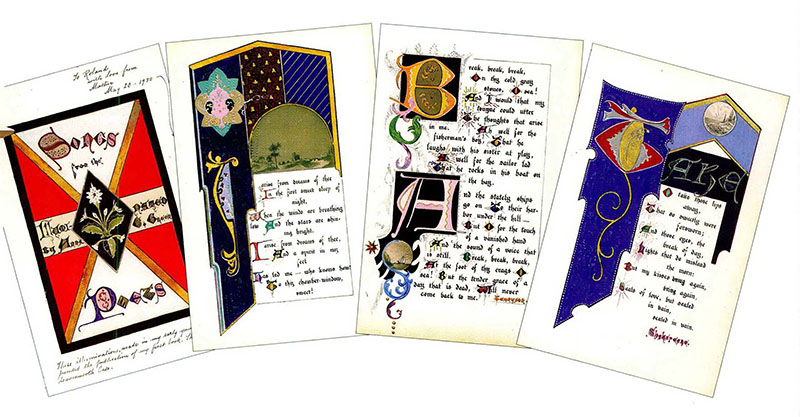

For the earliest mention of Rohlfs’s design and manufacture of furniture, we must return to the months just before the move to Buffalo. In a diary entry dated March 20, 1887, he wrote, “We have a mahogany chair in the corner of the stair-landing. Rosamond was the first to sit in it—it is her chair. . . . This chair together with the mahogany mantel-shelves in the dining room are specimens of designing and workmanship of Rosamond’s Mother and Father, both pieces of furniture being recent additions to our stock.”1 The offhand nature of the reference to the mahogany chair is notable in that Rohlfs neither declared it his first furniture effort nor made much of it as an addition “to our stock.” Thus, by March 1887, he had quite possibly been designing and making furniture for several months, if not years. Equally important is the casual revelation that the objects were examples of the design and workmanship of both Rohlfs and Green. That her contribution is not highlighted suggests that this was by no means the first time they had collaborated on furniture for their house.In addition to herliterary career and the general decoration of the family’s houses, Green’sartistic pursuits are known to have included watercolor painting and theillumination of poetry. Probably in the 1860s, perhaps during her years atRipley Female College (now Green Mountain College) in Poultney, Vermont, shecreated a set of illuminated poems entitled “Songs from the Poets” (see Fig.6), a beautifully rendered set of drawings with text that provides compellingevidence that she had a role in the design of the settee in Figure 5, whichis almost certainly the earliest surviving object created by Rohlfs andGreen.2 The carved ornamentation onthe settee is both whimsical and virtuosic, but it is not integrated into theoverall design. Largely kept to the periphery and the center of the seatapron, the ornaments seem to float on the boards they adorn. Those on theinterior surfaces of the arm supports resemble plumes ascending dramaticallyupward before turning back downward and spiraling inward (see Fig. 5a). Suchfeather motifs, a favorite Victorian design, connect closely to thenineteenth-century decorative styles in which Green had been steeped, as ismanifest in the similarly arced ascent of the I that begins her illumination of “The IndianGirl’s Song” by Percy Bysshe Shelley (see Fig. 7). Similarly, the lowerplumage of the I and the spiralingflourish below the B beginning “Break, Break, Break” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (Fig. 8), are related to the smaller feather motif that decorates the upper right and left posts of the settee (see Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5. Settee designed and made by Rohlfs and Green, c. 1888, for their own house. Oak with brass screws; height 32 1/4, width 57 1/2, depth 23 7/8 inches. Private collection; photographs by Keystone Productions.

The case for Green’s role in the decoration of the settee strengthens as we turn to the ends of the seat apron, where tripartite scrollwork spins two secondary curves off a central spiral (see Fig. 5c). This triple-curve motif figures prominently throughout her illuminations, perhaps most clearly in the delicately meandering design below the T in “Take, O take those lips away,” from the opening line of act 4 of Measure for Measure by Shakespeare, one of hers and Rohlfs’s favorite writers (Fig. 9). The more modernist geometric designs carved into the ends of the seat and on the feet are likely by Rohlfs, while a symmetrical motif in the center of the apron could be the design of either husband or wife. However, its trailing rhythmic dotting appears frequently in Green’s work, such as below the ornament framing the small watercolor seascape at the bottom of “Break, break, break.”

Taken together, these comparisons make a strong case for Green having played an essential role in the ornamentation of this earliest known Rohlfs object and thus for the claim that the couple collaborated on furniture previously attributed to Rohlfs alone. This really should not be too surprising because Rohlfs and Green worked together in other creative efforts. While touring Europe in 1890, they collaborated on various drawings in the family’s travelogue and on a second dramatization of her most successful novel, The Leavenworth Case of 1878. Rohlfs would later take the lead role in a national tour of the production of that drama in 1891, which marked his return to the stage.

Left to right: Fig. 6. Title page of “Songs from the Poets” by Green, 1860s. Watercolor on paper, 12 1/2 by 9 1/2 inches. Rohlfs family archive.

Fig. 7. Illumination for “The Indian Girl’s Song-‘ by Percy Bysshe Shelley, by Green, in her “Songs from the Poets,” 1860s. Watercolor on paper, 12 1/2 by 9 1/2 inches. Rohlfs family archive.

Fig. 8. Illumination for “Break, break, break” by Alfred Lord Tennyson, by Green, in her “Songs from the Poets,” 1860s. Watercolor on paper, 12 1/2 by 9 1/2 inches. Rohlfs family archive.

Fig. 9. Illumination for “Take, O take those lips away,” from the opening lines of act 4 of Measure for Measure by William Shakespeare, by Green, from her “Songs from the Poets,” 1860s. Watercolor on paper, 12 1/2 by 9 1/2 inches. Rohlfs family archive.

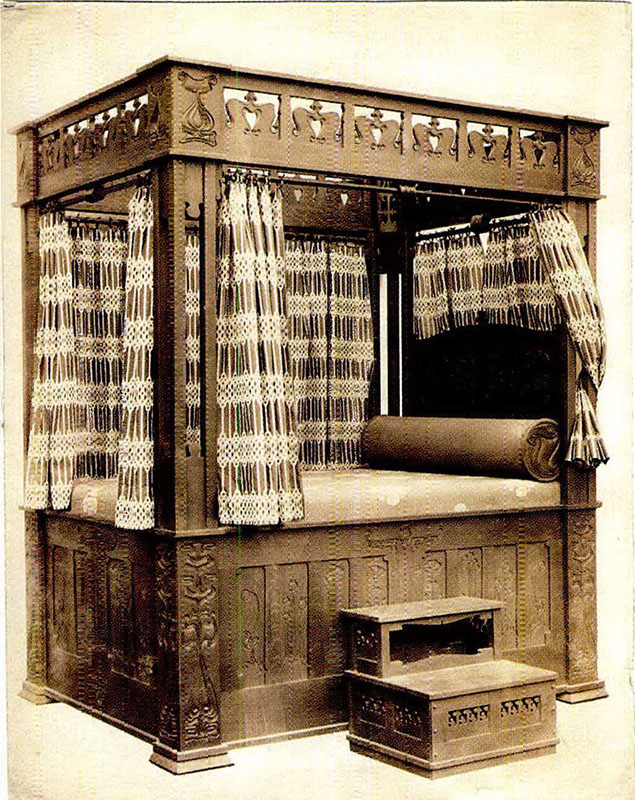

Rohlfs did not pursue furniture making as a profession until around 1897, after his acting career had fizzled, but even then Green contributed to his furniture designs. In January 1900, in the first article published about Rohlfs’s furniture, Charlotte Moffitt noted Green’s contributions, reporting in House Beautiful that Rohlfs’s “furniture is not turned out rapidly, for, excepting for the assistance of his wife, who is better known as Anna Katharine Green, Mr. Rohlfs does the work himself.”3 Green’s role in at least two important works is confirmed by visual analysis and archival records. Around 1898 to 1899, within two years of establishing himself as a furniture maker, Rohlfs began work on what has become his most iconic work, which he called the “Graceful Writing Set.”4 Comprising the only two objects he ever produced in any significant numbers—a fretted tall-back chair and a carved and fretted fall-front desk that swivels on a footed base (Figs. 2, 10)—the set was first published in 1900.5 Adorning the top of the desk are carved and fretted flamelike finials made of seemingly interlocking strands of oak, each actually carved from a single piece of wood. Evidence that Green contributed to the design is found on the cover of her novel Doctor Izard (1895), which shows a graphic image of a flame (Fig. 11, right) that relates closely to her illuminations and also bears an unmistakable resemblance to the design of the desk’s finials.A monumental canopied bed by Rohlfs also featured carved motifs that closely resemble graphic elements from the cover of a book by Green. Although its whereabouts is unknown today, the bed descended through the Rohlfs family and is shown in the period photograph in Figure 12. The panels of carved wildflowers recall the sinuous tall-stemmed ones on the cover of Green’s Lost Man’s Lane, published in 1898 (Fig. 11, left). This cover graphic, expressing an elegant femininity that suggests she designed it, reinforces our understanding of Green’s contributions to motifs on Rohlfs’s decorative art. Inscribed on the back of the photograph are the model number “32,” the price “$350” (the highest documented price for a Rohlfs object), and “Anna K Rohlfs,” underscoring her connection to the bed. Michael James has suggested that it was made for Green,6 but given that it was exhibited by Rohlfs at the Pan-American Exposition in 1901, and that the price suggests that it was meant for sale, it seems more likely that the notation indicates that the bed was designed with her input, and not that it was a singular piece made for her.

Among the most exquisite of all Rohlfs objects is the desk chair in Figure 4, made around 1898 or 1899. Its design is radical and the carving sublime. James, who labeled it a “Ladies’ Desk Chair,” suggested that it too was designed by Rohlfs for his wife,7 but I believe she collaborated with him on the design, and I have not found any evidence to suggest that this work of sculptural furniture was intended particularly for ladies. A sepia photograph of the chair in the Rohlfs family archive is inscribed in pencil on the back, “15/Desk Chair/Anna K. Rohlfs,” while the chair itself bears a Rohlfs workshop paper label inscribed “#4 Carved Desk Chair.” The presence of model numbers on the photograph and the label (why “4” in one place and “15” in the other has not been determined) suggests that the chair was intended for sale, and nowhere is it specifically denoted as made for Green. In fact, her name as given in the inscription on this photograph and on the one of the chair previously discussed is not one by which she is otherwise ever referred to—not in letters, diaries, or other communications as a wife, mother, or author—and almost certainly indicates her partnership with her husband in the design of these pieces of furniture. The carving on the chair back, representing a magnification of the cellular structure of oak, may reflect her mystery writer’s interest in science, for she was one of the very first writers to employ scientific evidence as a crucial part of her murder mysteries and courtroom dramas.

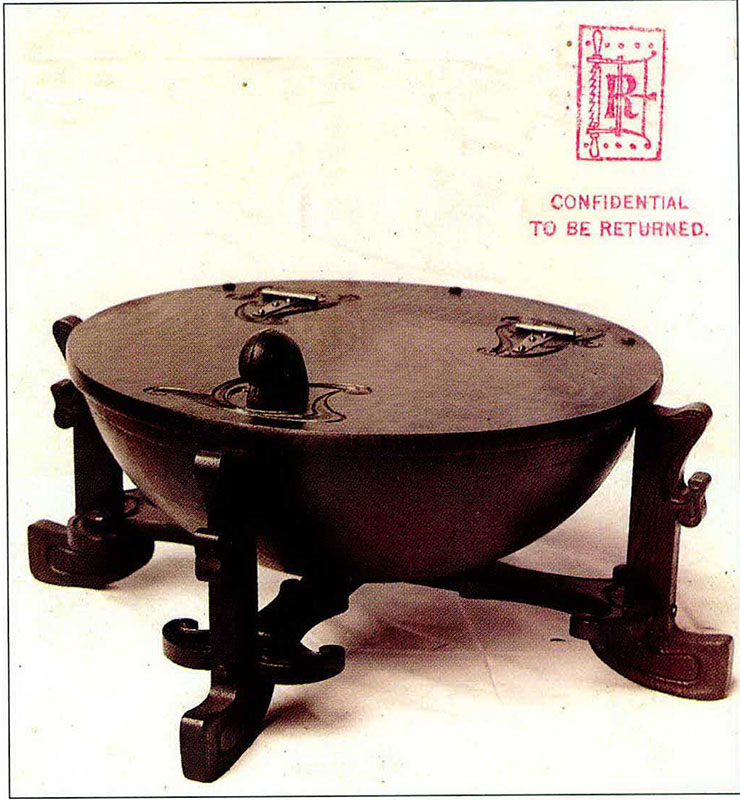

Charlotte Moffitt’s article in House Beautiful illustrated a “coal-box,” or “Coal Hod,” as Rohlfs referred to it (Fig. 13).8 The swirling scrolls that envelop the hinges and handle on the lid float almost carelessly across the oak surface. Perhaps the ornament was an afterthought, something Rohlfs added as an embellishment after conceiving the overall structure, without attending to its lack of integration with the carved legs and stretchers below. Once again, however, the decoration is similar to Green’s illuminations in “Songs from the Poets.” Moreover, the disconnection of the ornamental carving from the whole is reminiscent of that on the settee discussed earlier and may be an indicator of her participation. For a later, 1901, example of the coal hod, Rohlfs created an exquisitly carved motif that is much better integrated with the form.9

I have found little evidence for Green’s involvement in Rohlfs’s designs after 1900. But in all their endeavors they shared a lifelong commitment to each other and a love of art and design, as the works illustrated and discussed here so clearly demonstrate.

1 Entry dated March 20, 1887, in the diary kept by Charles Rohlfs and Anna Katharine Green for their children Rosamond and Sterling Rohlfs, Charles Rohlfs Papers, Joseph Downs Collection, Winterthur Library, Delaware. 2 Rohlfs pictured the settee in a drawing entitled “Corner in the study of Ann[a] Kath[a]rine Green” of c. 1888, which is illustrated in Joseph Cunningham, “Conversations in western New York: Charles Rohlfs and Gustav Stickley,” The Magazine Antiques, vol. 178, no. 5 (May 2008), p. 122, Fig. 6. 3 Charlotte Moffitt, “The Rohlfs Furniture,” House Beautiful, vol. 7, no. 2 (January 1900), p. 82. 4 Quoted in Will M. Clemens, “A New Art and a New Artist,” Puritan, vol. 5 (August 1900), p. 592. Rohlfs also referred to the desk as a “Swinging Writing-Desk” and the chair as a “Hall-Chair” in Moffitt, “The Rohlfs Furniture,” pp. 83 and 85, respectively; he referred to the latter as simply “Chair” in “Furniture: Designed and Made by Charles Rohlfs,” Art Education, vol. 7 (January 1901), p. 226. 5 Moffitt, “The Rohlfs Furniture,” pp. 83 and 85; and Lola J. Diffin, “Artistic Designing of House Furniture,” Buffalo Courier, April 22, 1900, p. 5. 6 Michael L. James, Drama in Design: The Life and Craft of Charles Rohlfs (Burchfield Art Center, Buffalo State College, Buffalo, 1994), p. 63. 7 Ibid., p. 67. 8 Moffitt, “The Rohlfs Furniture,” p. 81. 9 Illustrated in Joseph Cunningham, The Artistic Furniture of Charles Rohlfs (Yale University Press, New Haven, and American Decorative Art 1900 Foundation, New York, 2008), p. 90.

JOSEPH CUNNINGHAM, the curator of the American Decorative Art 1900 Foundation in New York, is organizing a traveling exhibition entitled The Artistic Furniture of Charles Rohlfs, opening at the Milwaukee Art Museum next year, and he is the author of the accompanying monograph.