Welcome to the inaugural edition of Dispatches, a new e-newsletter from The Magazine ANTIQUES written by Advisory Editor Elizabeth Pochoda.

To provide more value for our readers, we are expanding our digital coverage of niche topics. Dispatches is the first of these new digital-only offerings, an independent subscription from The Magazine ANTIQUES. We’d love your feedback on what topics interest you the most, so please fill out our quick survey.

We invite you to support Dispatches and [tinypass_offer text=”subscribe today”] for $5/mo to receive it in your inbox and have access to it on our website. Please enjoy a one month free trial during our February launch as well as your complimentary edition below.

For more details and answers to frequently asked questions, please visit our website page. We look forward to hearing your feedback.

Do you have a tip for Dispatches? Send it to us at dispatches@themagazineantiques.com

It can’t happen here… can it?

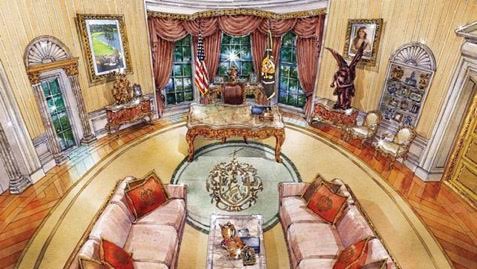

Maybe not, but this imaginary mock-up of a Trump designed Oval Office, is only one among many japes now aimed at the new president’s taste for 1980s style glam or gorp (depending on your point of view). To inject a little sanity into the matter, the January/February issue of Antiques has an important essay by Glenn Adamson explaining why the vulgarity police should holster their guns.

Credit: The Hollywood Reporter

I agree with Glenn and yet I know there is a deeper anxiety at large in the land and it has to do with the White House as a symbol of permanence amidst the inevitable flux of democracy. As the most redecorated house in history, it is, appropriately, a flexible symbol, but how flexible, we might ask. And what are the rules governing its contents?

Here is the official version: In the wake of Jacqueline Kennedy’s work restoring period décor to the White House, an executive order of 1964 laid out the role of the Committee for the Preservation of the White House and the White House Curator’s Office. In short, the first family has complete discretion in decorating the private quarters as they wish. The public rooms, however, are to be overseen by the committee (preservationists, museum curators, and art historians, some of whom serve for a year while others stay for decades). Charged with preserving the “museum character” of these rooms, the committee has, for instance, substantially rethought the décor of the Blue Room and the Lincoln Bedroom to mention two busy projects from recent administrations.

https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/codification/executive-order/11145.html

So far so good, although there is an interesting and rarely mentioned caveat in a 1961 law that precedes the 1964 order; it allows a president to override the committee and make decorative changes in the public rooms even if he (or she) is advised not to. This has never happened. Stay tuned.

Recent press coverage, playing to public curiosity about a possible Mar-a-Lago makeover of the WH, has focused somewhat hysterically on what I would consider nothing more than symbol manipulation. In his first week President Trump installed a bust of Churchill in the Oval Office along with gold drapes (left by a previous administration) and a rug designed for Laura Bush. All presidents do this kind of thing. But as I say, stay tuned.

A zeitgeist shift at the Winter Antiques Show, Christie’s, and Sotheby’s

After a flattening out in sales and enthusiasm over the past decade or so, early American furniture and decorative arts did quite well at the Winter Antiques Show in New York and at the January Christie’s and Sotheby’s auctions where total sales hovered just above 30 million. Read this as you will. I see it as a vote for democratic values and thus the right moment to consider what the antique furniture and decorative arts in the White House should mean to us. As I never tire of pointing out, they were this country’s first great art, the expression of the artisans who were freed from the constraints of the European guild system to be exuberantly and decidedly American.

It is the time to see these decorative arts as reminders of what it took to build this country and who did the building… including those African Americans, enslaved and free, who were not just sawing wood or tending fires in the shops of cabinetmakers and silversmiths. There is scholarly work to be done, public attention to be paid. If there is controversy about the furnishings of the White House, so much the better. It can, if properly met, shine a light and on a decorative arts heritage too often overlooked.

So there we have it: the people’s house, a flexible, mutable symbol with real tables, chairs, sideboards, and paintings to be praised, protected, and moved about under, one hopes, the stewardship of the curator and the committee. Even there we must expect judicious changes. To wish it otherwise, to want an unchanging past, a White House theme park, is one way to kill history…and maybe democracy too. There are, of course, others.

Politically Uncorrected

Down in New Orleans, the Historic New Orleans Collection, a museum now committed to delivering history straight, will follow up its attendance-breaking records for Purchased Lives: The American Slave Trade from 1808 to 1865, with a new exhibition, Storyville: Madams and Music (April 5 to at least the end of the year).

This may sound like a juicy come-on but HNOC doesn’t play it that way. The first floor of the exhibition will show how music (King Oliver, Jelly Roll Morton, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band) and dance (the black bottom, the slow drag, the one-step and two-step) emerged from the bordellos of Storyville.

Upstairs there will be a display of the notorious Blue Book guides to the madams and their prostitutes distributed for the benefit of the male and pale during the twenty years between 1897 and 1917 that Storyville was allowed to exist as a legal entity for prostitution just north of the French Quarter. In conjunction with the exhibition HNOC has just published Guidebooks to Sin: The Blue Books of Storyville, New Orleans, a crisp, scholarly and revealing volume.

That there was misery as well as gaiety in the bordellos of New Orleans is axiomatic, but the Blue Books do not hint at money or misery. Their historical value lies in the preposterous language they used to upscale sex, wink at miscegenation, and cloak various sexual practices in euphemisms that are fun to decode today.

Storyville was a stratified society that nevertheless allowed the races to mingle, supplying codes in the Blue Books for white (w), colored (c), octaroon (o), and Jewish (j). Once the forces of Jim Crow joined those of moral crusaders, Storyville was shut and shades of black, brown and beige vanished, turning the world either black or white.

Before that happened jazz was born. Storyville: Madams and Music marks the 100th anniversary of the first jazz recording: the Original Dixieland Jazz Band’s “Livery Stable Blues.” It also marks the centenary of the district’s demise.

(While HNOC is delving into significant areas of local history I hope that it will one day mount an exhibition on the craft and culture of free people of color, a rich tradition that vanished with the Civil War.)

New questions about Old Masters

I am unaccountably drawn to fairs, galleries, and auctions that display Old Master paintings for sale. I have no expertise in the field and have actually absorbed much of what I know from James Gardner’s beautiful articles in Antiques, and yet I am thrilled when I see these paintings in the marketplace where they feel approachable and somehow vicariously mine. Just now, however, I am disappointed and disillusioned.

A flurry of recent reports about high-end forgeries of Parmigianino, Frans Hals, Cranach, and other Old Masters all point back to a mysterious Frenchman, Giulano (also sometimes spelled Giuliano) Ruffini. The paintings in question seem to have no provenance apart from having passed through his slippery hands. Interestingly, Ruffini did not attribute any of them to a specific artist; he simply offered them to top flight dealers who decided on their attribution.

Although some experts did raise doubts about authenticity, museums such as the Louvre and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in two instances, did not.

When chemical analysis revealed the presence of modern synthetic pigments the game was up, but questions remain. Who is Ruffini and why is there no profile of him anywhere in the arts press and only one very sketchy old photo of him online? Where did these excellent forgeries come from? Are there really as many as twenty-four of them out there? When forgeries have been sold for prices in the millions, does it destabilize the Old Master market…and if not, why not? If it takes the time-consuming and expensive process of pigment analysis to discover fraud, how reliable, one departing exhibitor asks, is the vetting at a great art fair such as TEFAF?

I am following l’affaire Ruffini on Bendor Grosvenor’s lively blog (“Art History News”), hoping that he or someone at The Art Newspaper will enlighten me… and reassure me too.