Drawn to restaurants as settings for his stylish avatars of American anomie, Edward Hopper deliberately avoided giving them anything to eat.

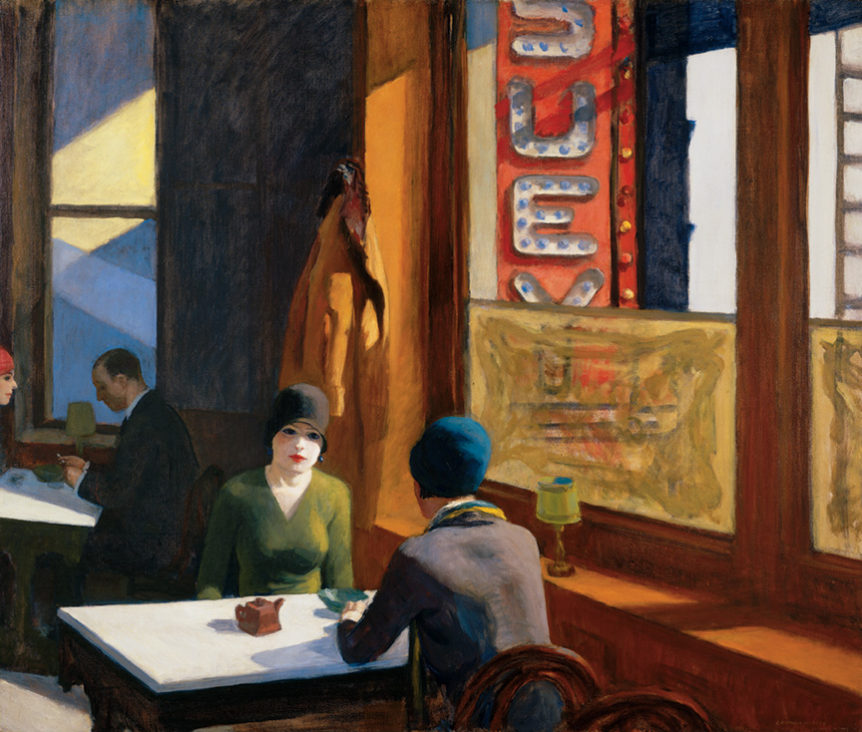

Chop Suey by Edward Hopper (1882–1967), 1929. Oil on canvas, 32 by 38 inches. Collection of Barney A. Ebsworth; photograph courtesy of the Seattle Art Museum.

The painter Edward Hopper seemed to care a great deal about what he put on his back, but not so much about what he put in his mouth. Photographs from the 1930s and ’40s show a man with a stylish, if traditional, sartorial approach. Sometimes he wears deliberately rumpled tweeds, as though emulating the look of an academic. (The critic Forbes Watson, a long time supporter and friend, once described him as “looking like a professor of higher mathematics in an outoftown college.”1) Sometimes he appears in a crisp black suit as be ts a New York man about town (Fig. 11). In a selfportrait drawn about 1936 and dedicated to his wife (Fig. 5), he caricatures himself as a continental country gentleman, sporting a Norfolk jacket, cape, and walking stick, a plume added to his customary fedora, and a monocle; at his feet is a basket of books in two languages, echoing the image promoted by his attire of a refined and erudite man.

Hopper was far less discriminating about his meals. He generally ate in cheap neighborhood restaurants, although for most of his career he could afford better. When he could cajole his equally ungastronomic wife, Jo, into cooking, their meals often centered on what they described as “the friendly bean.”2 They reciprocated dinner parties at friends’ homes with invitations to tea, and served storebought cake.3 His preferred cuisine was ordinary American. A 1943 trip to Mexico was nearly scuttled because of the “highly spiced Mexican food”; he found refuge in the hotel dining room where he could get a plain steak.4 Despite Hopper’s unadven turous approach to eating, a number of his most famous paintings are of restaurants. In them, people are often handsomely dressed, but sit at tables on which there is nothing to eat. In Hopper’s world of diners, tearooms, restaurants, and cafeterias, food is noteworthy by its absence. His subjects’ clothes are far more telling than their meals.

Even in his midtwenties, when Hopper made several trips to Paris, the world capital of fine cuisine, he was more engaged with fashion than with food. He made sketch after sketch of women in chic costumes and extraordinary hats (see Fig. 6) and of men wearing top hats, gendarmes’ capes, or the wide red pants of the soldier as indicators of their occupations and social status. Yet, even when sitting at restaurant tables, his subjects rarely have more than a wineglass in front of them. No still lifes, no images of bread, cheese, fruit, or other staples of the genre, are known from Hopper’s Paris years—in fact, still-life vignettes are extremely rare in his oeuvre.5

Hopper’s first major work depicting a café or restaurant, Le Bistro or The Wine Shop (Fig. 3), is a memory of Paris painted in New York in 1909. A bottle and glasses shared by two gures are the only tokens of sociability in this austere dreamscape. A similar emptiness characterizes Soir Bleu (Fig. 4), painted five years later. Here a café provides the setting for a gathering of disparate types, the kind Hopper enjoyed recording in his Parisian sketches: a man in military uniform with large epaulettes; a formally dressed bourgeois couple; a redbearded bohemian wearing a beret; a roughlooking man who may be a maquereau, or pimp; a woman whose lowcut dress and gaudy makeup suggest she is a prostitute; and a clown, all in white, his eyes downcast, who looks like a refugee from the commedia dell’arte. The wineglasses, empty carafe, and siphon on the tables do nothing to mitigate the uneasiness of the scene. Parisian cafés normally bring to mind good food and drink enjoyed in attractive company. But as Hopper would do in many of his restaurant paintings, in Soir Bleu he transforms a venue with pleasant associations into one that seems strange and not especially welcoming.

Places to eat would continue to provide Hopper with intriguing stage sets throughout his career. Viewers expect to see dining out portrayed as a convivial activity, and in New York Restaurant (Fig. 7) Hopper at first appears to meet those expectations. The room is crowded with whiteclothed tables and stylishly dressed diners. It is the end of the noonday rush, and the viewer is part of the busy scene. A waitress, wearing a white apron with a saucy bow, bends to clear dirty dishes. A man dressed in brown walks out of the picture to the right; presumably he has finished his meal. The man at left may be paying his bill; the woman in black standing near the door is probably the cashier. Hopper said his intent in this painting was to depict “the crowded glamour of a New York restaurant during the noon hour.” Glamour, perhaps, but not romance—not even much social connection. The man in the center of the picture looks to be more engaged with his soup than with his elegantly dressed companion. The cashier does not make eye contact with her customer. In fact, none of the figures appears to interact with another or to address the viewer. Hopper continued, “I am hoping that ideas less easy to define have, perhaps, crept in also.”6 As becomes evident in New York Restaurant, for Hopper social settings are more often marked by detachment than by camaraderie.

Hopper’s next major restaurant painting, Automat (Fig. 2), depicts a less upscale environment, one designed to provide a quick, inexpensive meal rather than a fine dining experience. Tremendously popular in the 1920s and ’30s, automats reflected the spirit of their age. Their facades were streamlined and their interiors often featured brass, chrome, and tile. Their very operation dramatized machineage modernity, as the deposit of a few nickels caused a turkey dinner or slice of pie to appear immediately from behind a glass door (Fig. 8).

Automats were noisy and cheerful, busy at most times of the day. They were clean, well-lit, and safe, and as such were especially hospitable to working women. Perhaps the diner in Hopper’s Automat is one of these. Or perhaps she is waiting for a companion as, eyes cast down, she nurses a cup of coffee. Nothing else—not a sandwich or a bowl of soup — is on the large marble table in front of her. In fact, she does not participate in the bustle of the automat at all: she sits by herself at the table nearest the door. There are no rows of glass doors or gleaming coffee urns in the picture; nor are there other patrons. Hopper suggests both her self-sufficiency—she is out in the evening without an escort—and a level of discomfort that he does not explain.

Yet with his acute sensitivity to the nuances of fashion, Hopper shows his young woman in clothes that underscore the precariousness of her social position. Her attire is up to date: her skirt falls just to the knee and her top has a squarecut neckline that emphasizes the “boyish” look fashionable in the mid-1920s. That style was an expression of women’s increased independence, their ability to move with greater freedom in the work world and society. While this woman’s attire is in style, it is not chic. Her clothes don’t quite make an ensemble. She wears a dark cloth coat with fur trim—presumably her good winter coat—with a hat whose bright yellow color and cheerful bunch of cherries at the brim are more suitable for spring. Like the table she chose in the automat, her clothes are less an expression of self-confidence than a defense against disappointment. She is both drawn to and out of step with the vitality of the restaurant and of the city beyond. She wants to embrace modernity, but remains somehow disconnected from it.

Two years later Hopper painted Chop Suey (Fig. 1), another picture depicting fashion-conscious women seated at a restaurant table. Their attire illustrates the change in styles at the end of the decade, and again Hopper incorporated that change and its social implications into his picture. The new styles were designed to accentuate a more curvaceous figure. The women’s tight-fitting sweaters, cloche hats, and made-up faces, which in a previous era would have marked them as sexually available, had become mainstream.

Chop suey restaurants offered inexpensive meals. The dish itself was invented in New York in the 1890s and within a decade there were chop suey restaurants all over the city.7 Their popularity continued through the 1920s and 1930s. They tended to have unexceptional decor—and to make that clear, Hopper concentrates all the pictorial excitement on the outside. He decorates the wall visible through one window with crisscrossed shafts of light and color, and through the other, he creates vertical rhythms from the rungs of the fire escape, the light bulbs, and the blocky lettering of the “chop suey” sign. The inside of the restaurant is far less animated. Once again, there is no food; the women’s table is bare except for a teapot and saucer. There appears to be no movement, no sound, no conversation. Instead, as John Updike so perceptively put it, “Both [of them] seem to be listening.”8

Fig. 9. Nighthawks by Hopper, 1942. Signed “e. hopper” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 33 1⁄8 by 60 inches. Art Institute of Chicago.

Chop Suey may have been suggested by a specific place. The Hoppers ate frequently at a similar spot near Columbus Circle,9 and although he did not mention a connection between that restaurant and the painting, he drew many of his subjects from his own experiences and observations. He did identify the setting of his most famous restaurant painting, Nighthawks (Fig. 9), as “Greenwich Avenue where two streets meet.”10 Recently the location has been pinpointed more exactly. Carter Foster, in his catalogue Hopper Drawing, has convincingly argued that the artist’s inspiration was Crawford’s Lunch, a restaurant that from the mid1920s occupied the corner of Greenwich Avenue and Twelfth Street. The artist walked in the area frequently, and may even have gone inside to sketch figures11—or to have a sandwich himself. Nonetheless, unlike Chop Suey, Automat, or New York Restaurant, in which he makes it clear that we are inside the dining room, in Nighthawks he places us outside, on the street, and provides no obvious point of entry.

As Foster observes, Hopper’s many figure studies indicate “the complex give-andtake between the real and the imagined” in the picture.12 Hopper apparently made sketches on the spot, but he and Jo also posed for the figures so he could refine their postures and gestures. The patron at the far left began as Hopper, wearing a favorite belted safari jacket Jo had bought him some years before (Fig. 10).13 The artist then swapped that rather sporty coat for a tightfitting suit and fedora pulled low to give the figure what Jo described as a “sinister back.”14 Another drawing, quite obviously of Jo, shows her pleasant facial features and fluffy bangs; her dress has a modest neckline. But in the painting she becomes a younger woman with hard features and brassy red hair, wearing a tight dress with a low, scooped neckline. Her companion, dressed in a well-tailored suit like the one Hopper wore for his photograph by Arnold Newman (see Fig. 11), has a profile as sharp as the brim of his hat. Hopper transforms nicelooking older people into hardboiled figures who appear as though they come from a Raymond Chandler novel.15

The tense, hermetic quality of their world is underscored by the long expanse of counter, bare except for a few coffee cups, napkin holders, salt shakers, and an empty glass left behind by a previous patron. There are no plates, no sandwiches, no pie.16 A normally inconsequential event—a late-night meal at a diner—is filled with foreboding. Once again we enter a world of stylishly dressed people who sit in silence in an almost empty restaurant, consuming nothing but cigarettes and sour coffee, as Hopper himself may have done, night after night.

CAROL TROYEN is the Kristin and Roger Servison Curator Emerita of American Paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

1 Forbes Watson, “A Note on Edward Hopper,” Vanity Fair, vol. 31 (February 1929), p. 98. 2 “The Silent Witness,” Time, December 24, 1956, p. 39. 3 Gail Levin, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography (Rizzoli, New York, 2007), pp. 263, 287. 4 Katharine Kuh, “Edward Hopper: Foils for the Light,” in My Love Affair with Modern Art, ed. Avis Berman (Arcade Publishing, New York, 2006), p. 272. 5 The sole examples seem to be the bowl of fruit in Automat (1927) and the vase of flowers in Room in Brooklyn (1932; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). 6 Hopper to Maynard Walker, January 9, 1937, quoted in Gail Levin, Edward Hopper: The Art and Artist (W. W. Norton in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1980), p. 51. 7 “Chop Suey Resorts: Chinese Dish Now Served in Many Parts of the City,” New York Times, November 15, 1903, p. 20, quoted in Patricia A. Junker, Edward Hopper: Women (Seattle Art Museum, 2008), pp. 34–35.8 John Updike, “Hopper’s Polluted Silence,” New York Review of Books, vol. 42 (August 10, 1995), p. 20, reprinted in John Updike, Still Looking: Essays on American Art (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2005), p. 188. 9 According to Levin, Intimate Biography, p. 221, the Hoppers were known to frequent a chop suey restaurant in Columbus Circle. 10 Katharine Kuh, The Artist’s Voice: Talks with Seventeen Artists (Harper & Row, New York, 1962), p. 134. 11 Carter E. Foster, Hopper Drawing (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 2013), pp. 106–108. Jo Hopper reported that he went to another diner, the Dixie Kitchen, to sketch the coffee urns. See Levin, Intimate Biography, p. 349. 12 Foster, Hopper Drawing, p. 111. 13 Levin, Intimate Biography, p. 349. 14 Jo Hopper in Edward Hopper Record Book II, Whitney Museum of American Art, p. 95. 15 For an insightful comparison between the setting of Nighthawks and an episode in Chandler’s 1939 novel The Big Sleep, see Judith A. Barter, “Nighthawks: Transcending Reality,” in Carol Troyen et al., Edward Hopper (Museum of Fine Arts, Bos ton, 2007), p. 209. Barter and Sarah Kelly Oehler also comment perceptively on Nighthawks in Art and Appetite: American Painting, Culture, and Cuisine (Art Institute of Chicago, 2013), pp. 34, 132, 198– 199. 16 Although it has been suggested that the woman is holding a sandwich (note that there is no plate in front of her) or perhaps a wad of cash, Foster argues persuasively that she is holding a pack of cigarettes. See Hopper Drawing, p. 116.