Although the earliest surviving illustrated botanical manuscript dates from AD 512-the Vienna Dioscurides, a copy of the important medical treatise by the first-century Greek physician and herbalist Pedanius Dioscurides-botanical illustration as a distinctive artistic genre developed in the fifteenth century with the rise of illustrated herbals, manuscripts explaining the medicinal and culinary uses of plants and flowers. After all, in an age living close to the ground, it was crucial to distinguish between a plant that could induce sleep and one that would induce it forever. The introduction of exotic new plants from Asia and the Americas during the sixteenth century prompted continuous publication of accurate pictures to help botanists study, name, and classify the new discoveries. Continued refinements to reproductive engraving and lithographic techniques furthered these publications during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Most techniques produced black-and-white images that were subsequently hand-tinted using watercolors, with mesmerizingly beautiful results.

An example is the plate in Figure 1, Balsamina foemina [Garden balsam]; Balsamina Mas fructu puniceo [Orange-colored balsam apple]; Momordica fructu luteo rubescente [Red balsam apple], from the first edition of Basilius (Basil) Besler’s Hortus Eystettensis, the earliest large folio florilegium, or botanical compendium, published in Nuremburg in 1613. Besler, a botanist and horticulturist, oversaw a group of artists including Sebastian Schedel who produced the 374 original colored drawings over a sixteen-year period. The prints illustrate European flowers, herbs, and vegetables as well as newly discovered plants such as tobacco and peppers. The drawings were engraved on copper by a team of masters, and this plate in particular not only presents an exceptionally high level of detail and botanical fidelity, but a beautiful composition. Besler issued the volume in black and white-with several initial luxury copies hand-colored by Georg Mack (one of these, formerly owned by George III, is in the British Library). However most hand-colored plates on the market today were tinted much later, including this one.

Rosa Gallica Maheka (flore subsimplici) comes from Pierre-Joseph Redouté’s Les Roses, published in Paris between 1817 and 1824 (Fig. 2). Redouté, a member of the French Academy of Sciences, was renowned for his exquisite flower paintings, which led to his successive engagements as art professor to Marie Antoinette, painter of flowers to Empress Joséphine, art teacher to Empress Marie Louise and thereafter to Marie-Amélie, consort of Louis-Philippe.

For Les Roses, Redouté collaborated with botanist and rose collector Claude-Antoine Thory (1759-1827). Each plate, based on a watercolor by Redouté, documents specimens taken from Thory’s own collections as well as others in the Paris vicinity, depicting cultivars that still survive and others no longer grown. The plates were stipple engraved, their shading and modeling produced by punching countless miniscule dots in the copperplate. Stipple engravings were usually printed in black and white, and tinted afterward with watercolor. The plates in Les Roses, however, were actually printed in color, in the method called à la poupée (French for “with a dabber”) meaning that each hue of stippled petals, leaves, veins, and stems was separately dabbed into the plate so that the blossoms would print with a natural appearance. Each print was then finished by additional hand-coloring.

Figure 3 shows another line engraving, the plate Ananas Sylvestris/Ananas sauvage--wild pineapple–from Johann Wilhelm Weinmann’s Phytanthoza Iconographia, published in Ratisbon, Germany, 1737-1745. Weinmann, revered as the apothecary of Regensburg, was renowned for his botanical research, and his book comprises an almost complete record of the flowers, fruits, and vegetables cultivated in the early eighteenth century. Eventually published in four folio volumes (though some sets are bound in eight) the collection of 125 plates depicts several thousand plant specimens, often several to a plate. Each plate, variously engraved from paintings by Johann Jakob Haid, Johann Elias Ridinger, and Bartholomäus Seuter, also exemplifies engraving à la poupée. Produced eight decades before Redouté’s roses, they are among the earliest specimens of multicolor printing from a single plate.

SWEET SOUTHERN DREAMS

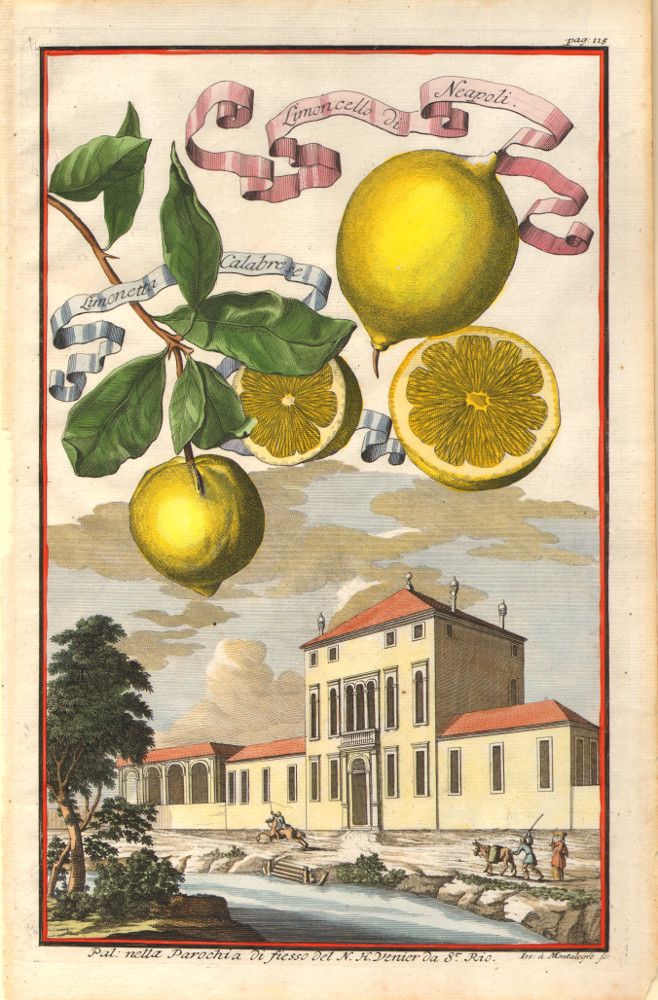

Decades before Goethe wrote “Knowst thou the land where the lemon trees bloom,” northern Europe enjoyed a fashion for constructing orangeries, essentially greenhouse rooms for the year-round cultivation of exotic plants. Potted citrus and palm trees imparted their fragrance, fruit, and lush foliage to these structures during the long winters, and inspired one of the most picturesque series of early eighteenth-century botanical prints, Johann Christoph Volckamer’s Nurnbergishe Hesperides (1708-1714), its name referring to the mythical garden where the golden apples grew. Engraved on copper and hand-colored in sun-bathed hues, Volckamer’s atmospheric prints combine detailed images of citrus fruits-in this instance (Fig. 4) Neapolitan and Calabrian lemons, what appear to be pomelos, and grapefruits, their names elegantly inscribed on floating ribbons-against backgrounds depicting villas and gardens in Italy and around Nuremberg, thus combining the spirits of botany and travel.

NATURE PRINTING

Leonardo da Vinci attempted to print images of plants by inking them and pressing them onto paper. The nineteenth-century Londoner Henry Bradbury developed a more successful method of “nature-printed intaglio,” and his Lastrea Filix mas cristata L. Filix mas polydactyla (Fig. 6), from Thomas Moore’s folio volume Ferns of Great Britain and Ireland (1855) shows how well the process was suited to reproducing the resilient textures of this botanical group. Bradbury’s process involved laying the plant to be illustrated on top of a plate of soft lead. The plant was then covered with a steel plate, and this sandwich was run through an intaglio printing press. The pressure forced the image of the plant into the soft lead, and this impression was transferred by electrotyping to a copperplate, from which a reverse plate was made for printing, which was done in colors.

WHAT A PEAR!

Though the bold colors, spare arrangement, and chocolate brown background seem remarkably modern, in fact the delectable print of Pears, Paddington, St. Martial (Fig. 5) comes from the late Georgian masterpiece Pomona Britannica or a Collection of the Most Esteemed Fruits (London, 1804-1812) by the noted painter and illustrator George Brookshaw. A celebrated cabinetmaker and colleague of Robert Adam, Brookshaw had specialized in painted furniture with floral, figural, and ornithological decoration (several of his pieces are in the Victoria and Albert Museum). After 1795 he shifted to teaching and to botanical illustration, dedicating to the Prince Regent (for whom he had been a cabinetmaker) his great volume of hand-colored aquatints lusciously depicting 256 species of British fruit.

Aquatint is a form of etching in which a covering of powdered resin is heat-fused to a metal plate. An alcohol or acid bath then bites the exposed metal between the resin grains, leaving a random texture of tiny dots (textures dependent on the manipulated size of the grains). Printing, usually in sepia ink, achieves a delicate tonality similar to wash drawing, and linear features of the image are usually strengthened with further line etching, while hand-coloring, as in this print, is an optional finishing step.

OF COLLECTING AND CONNOISSEURSHIP

Matters of artist, age, condition and edition all affect a print’s value. Earlier pressings usually command a premium, especially because as the copperplates wore, images from later pressings lost definition.”The paper used for printing and the quality and richness of the printed image can be clues as to whether an item is from an early or later pressing,” notes Jane Toczek of the Philadelphia Print Shop. Botanical subjects weigh in as well. “Tulips, roses and peonies are more popular subjects than, say, alpine wild flowers,” observes Tom McLaughlin of New York’s Donald A. Heald gallery.

Coloring is an especially hot button because most prints were issued in monochrome and colored at an indefinite stage thereafter, sometimes at the time of publication, often much later. “Most botanical or natural history images before 1720 should be black and white,” says Robert K. Newman of the Old Print Shop in New York. “The color revolution happened after 1700.” Relative to that is the question of restored color to a print that has faded after decades on a wall. “Most collectors know that engravings from Besler’s Hortus Eystettensis are often modern color” Newman says. “It is much more difficult to determine if a Weinmann or Redouté has been restored after the original color faded. A re-colored print should command half the price of an original colored print. However, in the case of Besler, the colored prints sell better and for more money, even though people know the coloring is new.”

As with most fields, new collectors are best advised to get their initial bearings by consulting a reputable dealer. In addition to those quoted here, noteworthy dealers include Daniel M. Belz in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, and George Glazer in New York, as well as Dinan and Chighine in Kew, Surrey, England.

PRESERVING AND DISPLAYING YOUR COLLECTION

Georgian and Victorian cabinetmakers produced superb print cabinets in mahogany and walnut, with wide, shallow drawers for ideal flat storage of large sheets. Today’s collector can choose to store prints in an antique piece, or those whose furnishing runs to Spartan understatement can easily find a commercial studio flat file for the same purpose.

“Loose prints can be safely stored in an archival “clamshell” Solander box with acid free tissue sheets between,” notes Denver dealer Tam O’Neill. “As long as they are handled carefully with cotton gloves this is a good option. Matting with kozo mulberry paper hinges on rag board is also a good option if the prints are to be handled frequently.”

As with all works on paper, light is an enemy, ultraviolet light a mortal one. For framing, Toczek advises “UV filter glazing on all framed items-either glass or acrylic as is suitable for the size of the artwork.” Newman says that one client frames a scan of each important print for hanging while storing the original in his library drawers. O’Neill says that “there is a clever collector here in Colorado who installed a series of picture rails in their stairway so that they can easily lean framed prints on the ledges, and change out the display often. The stairway has limited light so it’s perfect for works on paper.”

INTERESTED IN LEARNING MORE

“Patronage and the publication of botanical illustration” (Bernadette G. Callery, August 1989)

“Chinese botanical paintings for the export market” (Karina H. Corrigan, June 2004)

FURTHER READING

Lys de Bray, The Art of Botanical Illustration: Classic Illustrators and Their Achievements from 1550 to 1900

Wilfred Blunt and William T. Stearn, The Art of Botanical Illustration

Shirley Sherwood and Martyn Rix, Treasures of Botanical Art