The Magazine ANTIQUES | December 2009

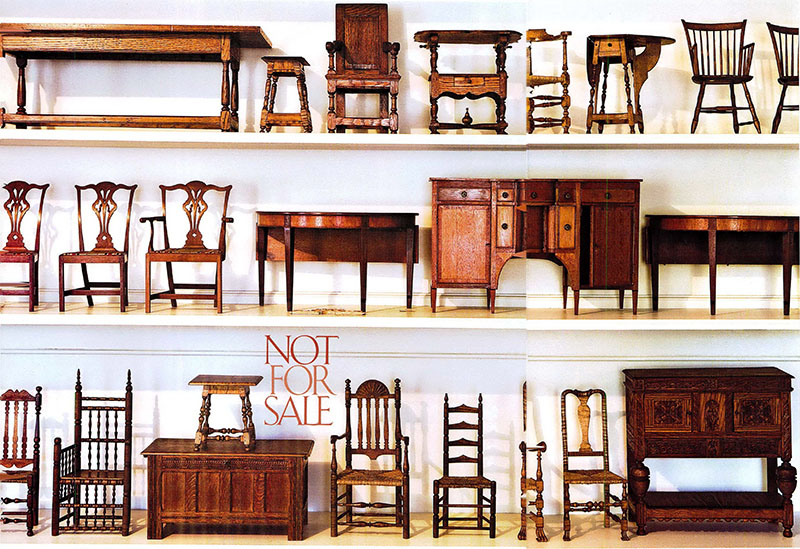

Fig. 1. Miniature furniture made by Ralph H. Keeler (1887-1976) of New London, Connecticut, 1920-1940. The objects illustrated are ill the collection of Arthur S. Liverant; photographs are by Ben Ritter.

The point of a gift is, presumably, to please the recipient. In this respect, the set of forty-five miniature reproductions of antique American furniture made by Dr. Ralph H. Keeler, a New London, Connecticut, dentist, for his daughter was a distinct disappointment. The late Israel “Zeke” Liverant, however, a Colchester, Connecticut, antiques dealer, found the tiny, exquisitely detailed chairs, tables, and chests irresistible. He seized the opportunity and bought the whole collection. Years later his son Arthur bought it again.

The first sale began with a telephone call from Keeler’s daughter in April 1966. It had taken her father two decades, roughly from 1920 to 1940, to create the miniatures, which he had given to her over a succession of birthdays and other holidays. She would have much preferred dolls, a bicycle, or a puppy, she told Zeke, and since her father had recently entered a nursing home, she finally felt free to dispose of what had been his passion, not hers.

When Zeke inspected what the daughter had, he was enchanted. The Liverants are known for their interest in objects of small scale; over the years an abundance of children’s chairs, miniature furniture, and other small objects has passed through their shop, a former Baptist meetinghouse. But the Keeler reproductions were unique. The wide range of styles, materials, and periods he explored was amazing, and the quality of the workmanship was even better. “Dr. Keeler was able to downsize the furniture without losing proportion,” Arthur says, “and he even gave careful choice to the quality of the woods.” What is more, as a dentist he had high standards when it came to fine fit and meticulous finish.

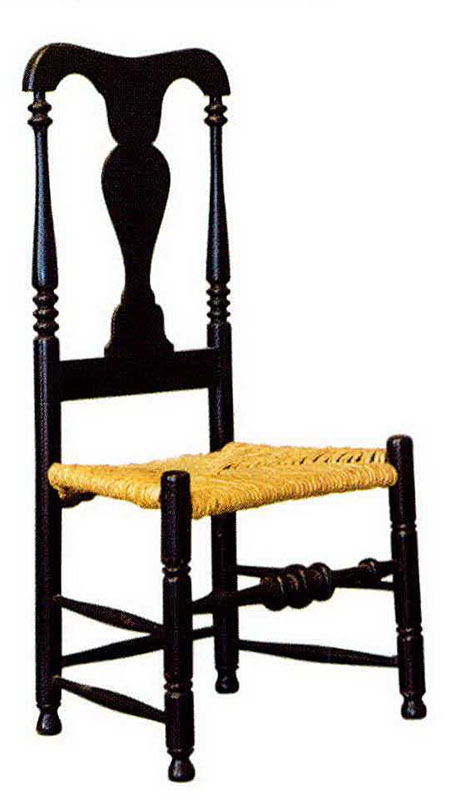

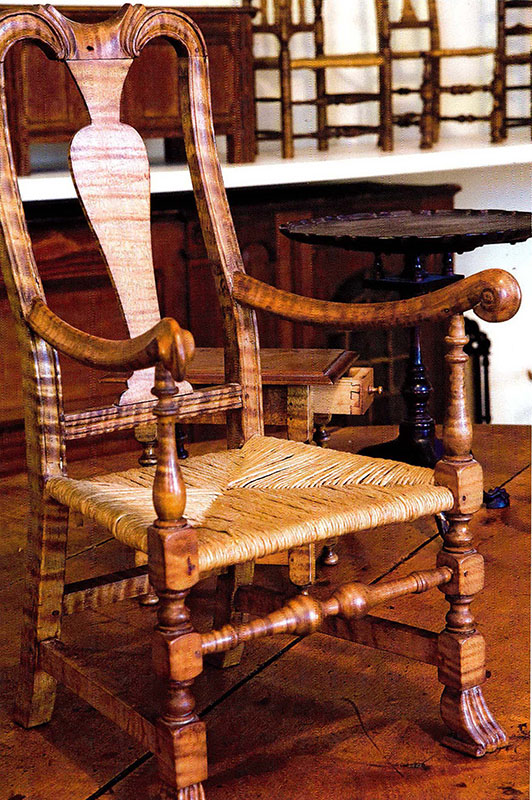

Thus, Keeler made small-scale windsor chairs with pinned spindles and wedged leg posts, and early joined great chairs with delicate turned spindles and finials. A freestanding corner cupboard sports a shell-carved back and a glazed door; a two-sided wall of paneling features one side from a country kitchen and on the reverse a formal sitting room with tombstone arched paneling (see Fig. 4). Keeler crafted his own miniature hardware for his creations: diminutive latches, hinges, and andirons. He also searched long and hard for just the right woods. For a Queen Anne figured maple Spanish-foot armchair (see Fig. 5) and matching side chair, he selected wood with an exceptionally tightly figured grain. In this way he managed to reproduce not just the form and joinery of the original, but also the wood graining in an appropriate scale.Keeler’s scholarship was almost as impressive as his display of technical skill: each of his pieces was fashioned with museum-quality authenticity. In fact, labels affixed to the furniture reveal that his collection, even if unappreciated by his daughter, had often been on loan to New London’s Lyman Allyn Art Museum.

Judging by the models he chose for his miniatures, Keeler was well acquainted with the Americana collections in a number of museums. Several pieces are copied from furniture at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Mabel Brady Garvan Collection at the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, and others. The Metropolitan Museum’s guide to the American Wing published in 1924 seems to have been one of the reference books in Keeler’s library. Among the illustrations in the guide (p. 83) is a view of a room from Newington, Connecticut, then on display at the museum. It shows a fine wall of tombstone arched paneling with engaged pilasters with rosette carved capitals and a raised panel over-mantel, as well as a glazed door shell-carved corner cupboard. This seems to have been the inspiration for Keeler’s sitting room and cupboard (see Fig. 4).

He may also have referred to a second, more complete illustration of the room as shown in the first volume of Wallace Nutting’s Furniture Treasury, published in 1928. Nutting’s book was influential in its time, so it is not surprising that eighteen of the forty-five objects Keeler chose to reproduce are illustrated in its pages. Then too the Nutting collection formed the basis of the Wadsworth Atheneum’s Americana collection, which was easily accessible to Keeler and must have been a frequent stop for him.

Zeke Liverant purchased the collection and brought it back to his shop, removing two of the miniatures to keep for himself. “My father was always on the lookout for the best, and I guess he decided to treat himself,” Arthur suggests. One of the two was a Philadelphia tilt-top tea table with acanthus-carved knees and carved claw-and-ball feet. The other was a continuous-bow windsor armchair with a red-painted surface. The tea table even had a handmade brass catch under the top, applied with three very small tacks and with a working spring on the inside. “Dr. Keeler did not make many case pieces of furniture, so the Philadelphia piecrust tea table represents the supreme accomplishment of the eighteenth-century cabinetmaker in the collection,” Arthur says. The windsor chair happened to be one of Zeke’s favorite forms.

The balance of the collection was in the shop that spring when the artist Nelson C. White (1900–1989) walked in for a visit. A painter of the Old Lyme school, White was a frequent visitor, and had acquired a number of antiques from the Liverants. He fell in love with the Keeler collection, possibly because Keeler had been a patron of the Old Lyme artists and had even traded dental services for paintings. “It is possible that Nelson knew Dr. Keeler and knew of the collection,” Arthur suggests. “In any case, he had to have them. Nelson was a flamboyant character, a scholar as well as an artist. His enthusiasm probably came from a personal association in addition to his genuine appreciation.”

Zeke, however, had trouble letting go of these treasures. He sold them to White on the condition that they would stay in the Liverant shop for the summer. White agreed and Zeke had his cabinetmaker, Konstantin Haliw, build display shelves for the two front windows of the shop. “I was a junior in high school when my father purchased the collection,” Arthur recalls. “They drew a great response. People would stand out there looking in with their noses pressed against the glass. It became a tourist event.”

At summer’s end, Zeke delivered the collection to White as agreed. The White family kept it intact, except for Zeke’s two pieces, until September 2002. Then the phone rang again at the Liverant shop. This time, it was Arthur’s turn to write a check. He brought the collection to Colchester for a second time. Shortly thereafter he considered bringing the miniatures to the Philadelphia Antiques Show. Doing so involved a special dispensation from the show committee, since the collection is more recent than objects typically permitted in the show. The committee was enthusiastic, believing that the furniture would generate considerable excitement. As the date of the opening drew near, however, Arthur had second thoughts.

“I remembered the collection so well,” he says. “When we had an opportunity to buy it back it was very exciting, and then when I had the opportunity to study the pieces and show them to clients, customers, and friends, everybody just swooned over it.” He began to see that the miniatures also offered a great way to show clients another way to appreciate American furniture. “I quickly realized that there was always an opportunity to sell them, but once they were gone, there probably wouldn’t be an opportunity to get them back a third time. To be honest, I just couldn’t part with them.”

Looking at these forty-five Lilliputian masterpieces, one cannot help imagining the dentist and patron of the arts hunched over his workbench, turning a spindle on a tiny lathe, or drilling a different sort of cavity with his dental tools. Keeler may have misjudged a little girl’s taste. His scholarship and artistry, however, remain impeccable.

The Dealer

By Tom Christopher

The headquarters of Nathan Liverant and Son is a former Baptist meetinghouse on the main street of Colchester, Connecticut. The main room is filled with gems of eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century American decorative arts: clocks, chairs, piecrust tables, blanket chests, silver, and oil paintings. Yet when Arthur Liverant, the current proprietor, wants to evoke the firm’s history, he points to a framed document on the restroom wall. It’s an auction notice dated October 16, 1930, published by one “N. Liverant,” Arthur’s grandfather and the dealership’s founder. “This will be a Clean Sale” the notice promises. “There will be No By-Bidders or Boosters.”

Nathan Liverant and Son has come a long way since the firm opened in 1920 but Arthur still honors his grandfather’s business practices—straight dealing and connoisseurship without pomposity.

The history of the firm is classic Americana in its own right. Nathan, the founder, left Russia by himself at age eleven and arrived in Ellis Island in 1901. He discovered Colchester while helping to deliver a load of Harris tweed to a local coat factory and he liked the historic ambiance of the town. During the Great Depression he began purchasing the contents of foreclosed houses in wealthy New York suburbs and bringing them back to Colchester to retail to local farmers and townsfolk. Israel (Zeke), his son and Arthur’s father, had an eye for antiques. As a boy he salvaged hand-forged nails from the ruins of old houses, and during his teens he helped to change the focus of the business when he identified an early eighteenth-century silver salt shaker in a job lot of junk sterling and plate. From there, as Arthur recalls, it was a matter of “working your way up, trying to deal with better things all the time, refining your eye about good quality, good design, and good condition. And it was also a matter of learning about the history of these objects.”

At home, Arthur recalls, “‘antiques’ was spoken in the morning at breakfast. It was dinner music. It was the discussion around our house all the time.” Though he completed an undergraduate degree in economics, he never seriously considered anything other than joining the family firm, which he did in 1971.

The Liverant business model has always been “the tortoise rather than the hare,” Arthur explains. The idea is to deal openly with customers, to educate, and to count on this approach for repeat business and referrals. He describes its benefits by recalling an episode six years ago when a contact (Liverant is notably discreet about names and places) tipped him off about an eighteenth-century house in eastern Connecticut that had been on the market for a couple of years. Arthur and his associate Kevin Tulimieri drove over and found that the building still contained some of its original furnishings, including a portrait of a young woman that Liverant recognized as the work of John Brewster (1766–1854), a deaf-mute from the nearby town of Hampton and a renowned folk artist. Telling the owner of his discovery, Liverant made an offer for the painting. The owner was inclined to sell it at auction, but swayed by Liverant’s frankness, he agreed to let him explore the attic. There, leaning against the chimney, Liverant found a piece of framed silk on silk needlework in miraculously pristine condition. It had been stitched by Rebecca Warren, the girl in the portrait. Liverant persuaded the owner to let him sell the two objects as a set and, he adds, “they are in a great collection today.”

Liverant takes pleasure in such coups, but as the sign in the restroom suggests, he keeps them in perspective. His favorite hat is a baseball cap with the insignia “Rookie.” “I still feel like a rookie,” he says. “There’s so much to learn in this, so much to study and absorb.” He’s fifty-nine, and some of his friends are already retiring. When they ask him whether he’ll leave the business, he doesn’t hesitate: “Not a chance.”