May 2008 | By 1740 a colonial elite of well-to-do merchants and landowning planters had emerged in Virginia. With riches from tobacco production supplemented by investments in the profitable iron industry, they were fully prepared to engage artisans and to commission houses and furniture in the latest European styles that would express and solidify their economic status. This trend was particularly true in northern Virginia along the Rappahannock River, where a cluster of prominent, interrelated families—the Beverleys, Carters, Fitzhughs, Lees, Spotswoods, Tayloes, and Washingtons—names that became synonymous with early southern history—lived and prospered.1

Into this milieu came a group of eager entrepreneurial craftsmen from abroad. Over a period of roughly four decades, from 1740 to 1780, a cadre of British, and, in fact, primarily Scottish cabinetmakers, migrated and set up shop in the Rappahannock River valley’s thriving port towns. Once established, these master craftsmen secured the labor of apprentices and journeymen and, even more important, of highly skilled indentured servants, men formally trained in European cabinet shops who came to America seeking economic opportunity. Setting the usual notion of fashion transmission on its head, in which style travels in a straight downward line from court circles to common men, it was frequently these indentured servants who were responsible for maintaining the fluency of the Rappahannock River valley’s cabinet shops with the latest European styles. The region’s richly carved furniture, demonstrating the transitions from baroque to rococo to neoclassical, clearly illustrates this fact.

Figs. 2, 2a. Armchair, attributed to Thomas Miller (1748-1802), Fred ericksburg, Virginia, 1773-1774. Mahogany with walnut and oak; height 42 ½, width 27 ½, depth 18 7/8 inches. Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge No. 4, A.F. & A.M.; photographs by Gavin Ashworth.

In 1732 William Byrd (1674–1744) of Westover, a plantation on the James River in southern Virginia, visited Fredericksburg, then the most prominent town in the Rappahannock River region. He noted that it possessed “a commodious and beautiful situation for a town, with the advantages of a navigable river and wholesome air, yet the inhabitants are very few” with “only one merchant, a tailor, a smith, and an ordinary keeper,” and Susanna Levingstone, the widow of Williamsburg’s former theater operator, “who acts here in the double capacity of a doctress and coffee woman. And were this a populous city, she is qualified to exercise two other callings.”2 In the decade that followed Byrd’s commentary, Fredericksburg grew significantly, the rival towns of Falmouth and Port Royal emerged, and two Scottish-born cabinetmakers—James Allan and Robert Walker—arrived, settling in Fredericksburg and Port Royal respectively, and began producing furniture for the area’s burgeoning population.

Working in collaboration with his brother William Walker (c. 1705–1750), a talented architect and master builder, Robert Walker introduced some of the earliest and most elaborate baroque style carving seen on colonial Virginia furniture.3 In 1746 his shop produced for John Spotswood (1722–1758), the son of a former colonial royal governor, a set of one dozen mahogany chairs embellished with fashionable carving in the early Georgian taste (see Fig. 4).4 The key elements of Spotswood’s chairs—the dramatic shaping and scrolling of the crest rail, the heart-and-ribs piercing of the splat, the clamshells and husks carved on the legs terminating with claw-and-ball feet—established a new standard for Rappahannock River chair design and gradually evolved into the local vernacular style imitated by others.

In 1749 John Mercer (1704–1768) commissioned a set of fourteen chairs from the Walkers that document Robert’s reliance on a professional carver, probably an indentured servant, for the successful execution of his designs. According to Mercer’s account book he paid the Walkers £30.8 for the chairs, which included £10.16 in charges for fifty-four days of work by a carver at the rate of 4s per day, making the carver’s time and skill more than a third of the total sum. Referred to in the account book as simply “his Carver,” the possessive terminology used by Mercer implies a master-servant relationship between Walker and the carver. The account book further demonstrates that three months later, for an unexplained reason, Mercer sold the chairs back to William Walker at cost.5 Miraculously, an armchair from the set survives with a history of descent in the Walker-Ferneyhough family (Figs. 3, 3a). Nearly identical to the Spotswood chair, its gadrooned seat rail and the carved dog’s-head arm terminals represent additional core features of the Walker shop’s chairs.That Robert and William Walker had an indentured servant craftsman was not unique. In 1748 the Scottish-born clergyman Robert Rose (1704–1751) went to Fredericksburg and paid £28 for “a joiner from Mr. James Allan who has six years to serve.”6 Allan appears to have engaged indentured servants on a regular basis, for three years later he advertised in the Virginia Gazette for a runaway “Servant Man, named Thomas Gray…a Cabinet maker and Joiner by Trade…very talkative, much addicted to Drinking and plays well on the violin; was imported by Indenture from London in the Ship Rachel, Capt. Armstrong, this Summer.”7 Eventually captured and returned to Allan, Gray was sentenced by the county court to an additional six months of service.8 Robert Walker enjoyed a similar experience in 1755 when the King George County court “Ordered that Alexander Scott serve his Master Robert Walker according to Law for Fifty Eight days Runaway time.”9

Thomas Gray and Alexander Scott typify many of the skilled craftsmen who came to colonial America. With important skills but limited opportunities and no capital, they bargained a set amount of labor, frequently seven years, in exchange for food, clothing, shelter, and passage to North America. Once their ships landed in Virginia ports, local planters and master craftsmen could purchase their contracts from the ship’s captain and, for the predetermined number of years, they were the servants of their masters, occupying a legal status between that of slaves and freemen.

Could Alexander Scott be the carver mentioned in the Mercer accounts? Unfortunately, it remains a mystery. However, the accounts reveal that whoever he was, this artisan worked for both Robert Walker, the cabinetmaker, and William Walker, the architect, and so was cross-trained in architectural and furniture carving, a fact that sheds interesting new light on his work. Perhaps the earliest example of his work is the elaborately carved tea table in Figure 5, which descended in the Lee family of Stratford Hall Plantation in Westmoreland County. Produced shortly after Walker’s documented association with Thomas Lee (1690–1750) and the construction of his new house, the Lee family table combines the leafage, husks, and claw-and-ball feet seen on the legs of the Walker shop chairs with a turned drop pendant similar to those on the newel posts of staircases and carved imbrocation, or fish scales, frequently found on the architectural bolection moldings and trusses for mantelpieces and door surrounds (Fig. 5a).10

The death of William Walker in 1750 and the dissolution of his workforce created an architectural vacuum in northern Virginia, but surviving objects suggest that the unknown carver continued his affiliation with Robert Walker’s cabinet shop for at least another decade, presumably after his term of indenture had expired. The objects attributable to this artisan can be dated from the mid-1740s to around 1760.

An important group of objects demonstrates the Walker carver’s awareness of the style transition taking place from the late baroque to the early rococo. These include a tea table made for the illustrious Carter family at Cleve Plantation in King George County, Virginia (Figs. 1, 1a). Its elaborately shaped top is a tour de force of carving, the design of which may have been inspired by a silver salver made by the London silversmith John Swift (free 1725) in 1753/54 and owned by the Spotswood family.11 A very similar top is found on the kettle stand made for the Semple family (Figs. 6, 6a). On both the tea table and the kettle stand, the carving on the knees flows in two directions, rather than simply cascading down the legs as seen on the earlier Lee family tea table (see Figs. 1a, 5a). Altogether, these pieces convey a lightness verging on asymmetry that heralds the arrival of the rococo taste.12

William Walker’s untimely death came at the point when George Mason (1725–1792) was looking for craftsmen for the construction of his new house, Gunston Hall. In 1755 he turned to Europe for indentured servants, and with the help of his brother living in London, he procured a young architect and master builder named William Buckland and a carver named William Bernard Sears. Sears, identified in London records as “Barnard Sears, carver,” left England as a felon sentenced to seven years of indentured servitude in the North American colonies for stealing “one cloth waistcoat, one cloth coat, one pair of cloath breeches, four linnen shifts, two linnen shirts, twelve linnen aprons, and one guinea.”13 Buckland and Sears completed Gunston Hall, gained their freedom, and set out on their own, finding employment with John Tayloe (1721–1779) to build and furnish his new house, Mount Airy plantation, on the south bank of the Rappahannock River in Richmond County. There, they collaborated on two magnificently carved, marble-topped sideboard tables, including the one illustrated in Figure 7.14 A straightforward adaptation of Plate 38 in Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-maker’s Director (London, 1754), this table again illustrates the role played by indentured servants, even those who arrived as convicts, in delivering the latest British style to their patrons. By the mid-1760s James Allan’s shop in Fredericksburg appears to have acquired its own professional carver. A small group of chairs with distinctively carved splats, now attributed to the Allan shop, survive with histories in the vicinity.15 This important group includes the side chair illustrated in Figure 8, which demonstrates a carving style and construction techniques that are clearly different from the Walker shop’s chairs. Like the others in the group, it features an interlaced splat carved with rosettes and acanthus leaves, sometimes supplemented with clamshells and ribbons. Given his training before immigrating to Virginia in the 1730s, the up-to-date rococo fashion of these chairs would have been completely unfamiliar to Allan, but like Robert Walker, he came to the colonies with enough capital to create his own shop, to hire apprentices and journeymen, and on a regular basis to procure the skills of newly arrived craftsmen to insure that his offerings to customers remained suitably fashionable.

In 1765 significant competition arrived in Fredericksburg with Thomas Miller, another Scottish-trained cabinetmaker.16 Miller joined the local Masonic lodge and quickly followed the pattern of setting up shop and advertising in the newspaper for “Journeymen Cabinet-Makers, well recommended.”17 In the same issue he offered a reward of £3 for the return of a runaway indentured servant “George Eaton, born in London and imported last February in the Neptune, Capt. Arbuckle,” noting that “he is by trade a cabinet-maker, about 5 feet 3 or 4 inches high, 20 years of age, of a fair complexion, wears his own hair, which is short and fair, and sometimes wears a false curl, which a stranger would not know from his hair, being exactly of a color.”18 Four years later Miller sought the return of “a Convict Servant Man…William Jennings, by Trade a Cabinet Maker.”19

Such advertisements for runaways are too frequently the only reference to these obscure craftsmen, but the journal of John Harrower (d. 1777) offers a rare insight into the important roles they played in colonial Virginia.20 A bankrupted merchant from the Scottish Shetland Islands, Harrower bargained four years of his labor for transportation aboard the ship Port of London to Fredericksburg. Sailing up the Rappahannock River, he noted that “along both sides of the River there is nothing to be seen but woods in the blossom, Gentlemens seats & Planters houses.” Passing the port of Leedstown he observed “a ship from London lying with Convicts,” and upon arrival in Fredericksburg in May 1774, he described the sale of indentures for the barbers, coopers, blacksmiths, shoemakers, farmers, and cabinetmakers that were listed among the seventy-five passengers on the Port of London.21 His own contract was purchased on May 23 by Colonel William Daingerfield (d. 1783), a wealthy local planter, and he became a tutor in the Daingerfield household.

The Port of London’s official passenger list identified four furniture makers: Daniel Lakenan, a twenty-two-year-old cabinetmaker from London; Thomas Low, a seventeen-year-old cabinetmaker from Chester; John Tran, a twenty-year-old carpenter and joiner from Southwark; and Thomas Ford, a thirty-two-year-old carver and gilder also from London.22 Currently, no other references to these artisans are known, but the regular arrival of fresh talent helps explain the remarkable carving seen on furniture of the Rappahannock River valley.

Perhaps one of these men was responsible for the carving on Miller’s extraordinary Masonic master’s chair in Figure 2, which is today considered one of America’s earliest and best-documented expressions of neoclassical design.23 In the mid-1770s Fredericksburg’s Masonic Lodge paid Miller £5 for the chair. It is richly embellished with carved gardooning, floral decoration, and hairy paw feet (see Fig. 9). Indicating the carver’s British training, the frieze across the front seat rail is adapted from Plate 52 of Abraham Swan’s British Architect (London, 1758). To create a fashionable product for the lodge’s use, the carver utilized a full range of Masonic imagery on the crest rail and splat, with a sun, moon, columns, compass, square, sundial, and Bible surrounding the all-seeing eye.24 Subtle details betray his familiarity with the newly emerged neoclassical style. Specifically, his approach to the metopes and triglyphs carved on the shoe and the elongated husks on the arm supports bespeak his knowledge of the innovative designs of Robert Adam (1728–1792) and others from Great Britain.Like the Walker shop carver, the identity of Thomas Miller’s professional carver is a mystery, but a small cluster of his work survives in houses and on furniture produced in Fredericksburg from the early 1770s to around 1780—interestingly, roughly equivalent to the typical seven-year term of an indenture. Like the Walker brothers’ carver, he seems to have been cross-trained in both architectural and furniture carving.

His architecture portfolio includes the advanced carving found on chimneypieces at Kenmore, the residence of George Washington’s sister and brother-in-law, Betty and Fielding Lewis, and at the Chimneys, a house built in the late 1770s for Fredericksburg’s leading Scottish merchant, John Glassell (1734–1806).25 In furniture, his hand is also seen in a significant set of chairs made for the Waller family of Spotsylvania County and Williamsburg (see Fig. 10).26 The chairs feature one of the most iconic expressions of early neoclassical design, an anthemion, carved in each of the crest rails.

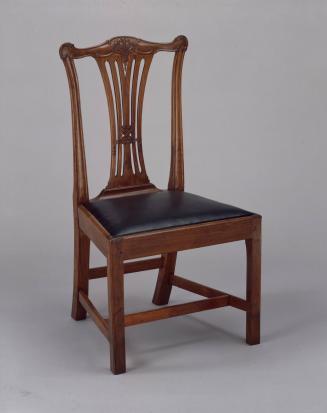

Clearly, not all furniture enjoyed the time and attention of the professional carver. Tho-mas Miller’s shop also produced plain style chairs such as the one illustrated in Figure 11, which descended in the Little family of Fredericksburg. It is nearly identical in construction and design to the Masonic chair and the Waller family chairs but is devoid of the adornment. Indeed, this chair recalls the set of “12 Black Walnut Chairs” made by Miller in 1774 for the local tavernkeeper, George Weedon, priced at only twenty shillings each, significantly below the price of carved chairs.27

Could Thomas Ford, the thirty-two-year-old carver and gilder from London who arrived in Fredericksburg with John Harrower aboard the Port of London on May 10, 1774, have been Miller’s elusive carver? He does not appear in any known records in the Fredericksburg area. But the importance of the thousands of indentured servants like him who came to America seeking new opportunities for professional expression should not be underestimated. The splendidly carved furniture of the Rappahannock River valley remains as a testament to the historical and artistic importance of these craftsmen, and radically subverts presupposed notions of “trickle-down” decorative arts.

Fig. 11. Side chair, attributed to Miller, Fredericksburg, 1770-1780. Black walnut; height 37 ½, width 21 ¼, depth 19 ¼ inches. Fredericksburg Area Museum and Cultural Center, gift of Genevieve Rowe Hunter; Ashworth photograph.

1 For Landon Carter’s 1738 estate on the Rappahannock, see Ralph Harvard, “A baroque Virginia treasure house: Landon Carter’s Sabine Hall,” The Magazine Antiques, vol. 173, no. 4 (April 2008), pp. 104–115. 2 William Byrd, “A Progress to the Mines in the Year 1732,” in The Prose Works of William Byrd of Westover, ed. Louis B. Wright (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1966), p. 368. 3 Robert A. Leath, “Robert and William Walker and the ‘Ne Plus Ultra’: Scottish Design and Colonial Virginia Furniture, 1730–1775,” American Furniture, 2006, pp. 54–95. 4 Ibid., p. 72. 5 Ibid., pp. 68–70. Mercer’s Ledger Book 1741–1750 is in the Mercer Museum, Bucks County Historical Commission, Doylestown, Pennsylvania. 6 The Diary of Robert Rose: A View of Virginia by a Scottish Colonial Parson, ed.Ralph Emmett Fall (McClure Press, Verona, Virginia, 1977), p. 29.7 Williamsburg Virginia Gazette, October 20, 1752. 8 Entry for November 8, 1752, Order Book, 1749–1755, p. 206, Court Records, Spotsylvania County, Virginia, microfilm, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Research Center, Winston-Salem, North Carolina. 9 Entry for October 2, 1755, Order Book, 1751–1765, p. 580, Court Records, King George County, Virginia, microfilm, ibid. 10 Leath, “Robert and William Walker,” pp. 66–67. 11 Wallace B. Gusler, “The tea tables of eastern Virginia,” The Magazine Antiques, vol. 127, no. 5 (May 1989), p. 1250. 12 Leath, “Robert and William Walker,” pp. 78–79, 80–81. 13 Quoted in Robert F. Dalzell Jr. and Lee Baldwin Dalzell, George Washington’s Mount Vernon: At Home in Revolutionary America (Oxford University Press, New York, 1998), p. 168. 14 For the other sideboard table, see Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown, Southern Furniture 1680–1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg , Virginia, 1996), pp. 264–269. 15 Tara Gleason Chicirda, “The Furniture of Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1740–1820,” American Furniture, 2006, pp. 101–103. 16 Ibid., pp. 114–115. 17 Williamsburg Virginia Gazette, September 22, 1768. 18 Ibid. 19 Ibid., June 25, 1772. 20 The Journal of John Harrower, an Indentured Servant in the Colony of Virginia, 1773–1776, ed. Edward Miles Riley (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1963). 21 Ibid., pp. 37–40. 22 Ibid., pp. 166–168. 23 For more about the chair, see Chicirda, “Furniture of Fredericksburg,” pp. 106–112. 24 For more about Masonic imagery, see Aimee E. Newell, “Celebrating 275 years of brotherhood: The Grand Lodge of Masons in Massachusetts,” The Magazine Antiques, vol. 173, no. 4 (April 2008), pp. 84–91. 25 For the chimneypieces at Kenmore and the Chimneys, see Chicirda, “Furniture of Fredericksburg,” pp. 116–117, Figs. 34–38. 26 Ibid., pp. 118–119. 27 Ibid., p. 122.

ROBERT A. LEATH is the chief curator and vice-president of collections and research at Old Salem Museums and Gardens, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.