In the early 1800s, annual exhibitions at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts were renowned for the American landscapes on view. These shows of paintings by artists such as Thomas Doughty and Thomas Birch placed Philadelphia at the epicenter of a burgeoning visual culture based around the environment of the new republic. Artists captured the beauty of the region’s waterways, woods, and country estates; celebrated advancements in science and technology that harnessed nature for a growing metropolis; and saw prints made after their paintings that were reproduced around the world, creating a global visual image of the new country.

Early painters of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers profoundly influenced the later generation of American artists known as the Hudson River school by way of its founder, Thomas Cole, who lived and studied in Philadelphia in the early 1820s. The Schuylkill River painters adapted British traditions of landscape representation to create a vision of the northeastern United States as a well-ordered and picturesque landscape, with Philadelphia as its artistic hub. In contrast to the grand romantic impulses of the Hudson River school painters, who often looked to a perceived American wilderness for inspiration, the artists working in Philadelphia in the early republic used landscape to craft an image of a progressive, prosperous, and industrious republic, where nature was tamed by the forces of American civilization. These were the visions of America that Cole admired at the annual exhibitions at the academy in his years there.

While these Philadelphia landscape traditions helped shape the work of the Hudson River school, the national and international travels of the artists, including Cole, Doughty, and Birch, expanded their influence beyond national borders, inspiring the work of US landscapists working in Europe and throughout the Americas, as far south as present-day Colombia and Brazil. From the Schuylkill to the Hudson: Landscapes of the Early American Republic, an exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy, explores the early influences on and of the Schuylkill River painters and surveys subsequent developments in American landscape painting at home and abroad.

British artistic practices provided an important foundation for American landscape traditions. The first professionally trained European artists to represent the landscape of what is now the northeastern United States and Canada were British military topographic artists such as Lieutenant William Pierie of the Royal Artillery, who completed a drawing of Niagara Falls “on the spot” in 1768. Pierie’s sketch, only the second known European drawing of Niagara, was sent to London, where Richard Wilson, England’s leading landscape artist, is purported to have used it as a reference for a large canvas—five by six feet. Wilson’s image was then engraved by William Byrne and published in 1774 in London (Fig. 2). Artists like Pierie were trained at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich, London, and it is for this reason that prints like Cataract of Niagara, while aesthetically pleasing, should also be recognized as colonial and imperial tools of both measurement and control.

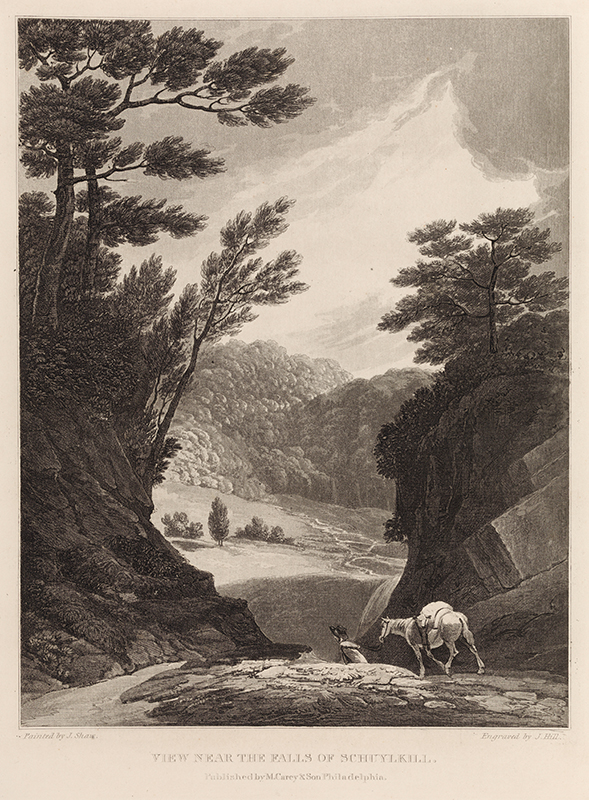

The British-born artist William Russell Birch conceived of his illustrated publication The Country Seats of the United States of North America, which appeared in 1808, while living at Springland, his four-acre, creek-side property not far from Philadelphia in Bucks County. Country Seats was an attempt by the artist to construct imagery of the new nation by depicting multiple views of elite suburban homes of the early republic, a tactic he took from such existing British traditions as landscape tourism and aristocratic country house portraiture. Birch’s work, however, was a financial failure, perhaps as a result of the developing tastes of an American populace eager to construct itself not as a new Britain, but as a different type of country—a democracy. His contemporary and fellow British immigrant Joshua Shaw was more successful with his artistic series Picturesque Views of American Scenery, 1820 (see Fig. 4), published twelve years after Country Seats. In these prints Shaw focused not on elite homes, but on the beauty of the region’s rivers and landscape, subjects more appealing to Americans who were self-consciously rejecting British aristocratic practices.

Shaw’s Falls of the Schuylkill and Thomas Doughty’s Land Storm (Fig. 5) are depictions of the Schuylkill in the style known as the sublime—the term used to describe paintings of storms, shipwrecks, waterfalls, and natural disasters that invoke a feeling of pleasurable anxiety in viewers. They stand in marked contrast to later paintings of the Schuylkill as controlled and contained. The damming of the river and the creation of the Fairmount Water Works, initially constructed between 1812 and 1815 on the east bank of the Schuylkill, fundamentally changed the waterway and its significance in every way. The more domesticated, scenic image prompted by this new technology was what would come to symbolize the new American republic on a national and international stage. These, as well as those by Birch and Doughty, were the paintings Cole would have seen on view at the Pennsylvania Academy in the early 1820s.

Cole once told art historian William Dunlap that during his time studying at the Pennsylvania Academy, “his heart sunk as he felt his deficiencies in art, when standing before the landscapes of [Thomas] Birch.” One of the paintings by Birch that might have had this effect on Cole is Fairmount Water Works, which was shown in the Pennsylvania Academy’s 1824 exhibition (Fig. 1). Executed in remarkably minute detail, the painting shows picturesque natural beauty and industry in harmony along the Schuylkill, including details of the new waterworks; the Schuylkill Canal; a steamship, a new sight in the days when the Norristown became the first to travel up the waterway; and the beauty of Lemon Hill Mansion perched atop the banks above the river. The structure we see celebrated in Birch’s painting is the millhouse erected after a dam was built across the river between 1819 and 1821.

Paintings by Doughty and Thomas Birch prompted an explosion of popular images depicting the Schuylkill that would travel around the world, disseminated through the distribution of prints that were then transferred onto tableware produced in Bohemia, China, Britain, and the United States for elite and middle class homes. Views of the Fairmount Water Works were often placed on vessels that held water—pitchers, basins, vases, and teacups. One of the most beautiful examples is a teacup and saucer hand-painted in China for the American export market (Fig. 7). It is no accident that this image of American health, of the purity and modernity of Philadelphia’s water source, was depicted on a teacup—tea being the preferred drink of “teetotalers,” who abstained from drinking alcohol. Such vessels were part and parcel of the international projection of Philadelphia as a virtuous, modern, and hygienic city.

The year 1825 was pivotal in the shift in artistic attention from the Schuylkill to the Hudson River, with the completion of the Erie Canal that year and its expansion in 1836. By 1850, traffic in the port of New York City—with its ready access to both the Atlantic Ocean and, via the Hudson and the Erie Canal, the Great Lakes—had eclipsed that of every other city in the United States. 1825 was also the year Thomas Cole left Philadelphia for New York and took his first voyage up the Hudson River, and it also marked the creation of the National Academy of Design in New York, which became the arbiter of American artistry for more than a century.

Following in Cole’s footsteps, successive generations of Hudson River school painters dominated the production and exhibition of landscapes in both Philadelphia and New York from the 1840s through the mid-1870s. In this period, Niagara Falls, near the terminus of the canal at Lake Erie, enjoyed ever-increasing popularity, and ultimately replaced the Fairmount Water Works as a symbol of the power of the nation. In Niagara, of 1878, Albert Bierstadt represents nature at its fiercest, with a darkened sky, foaming dark blue waters, and raw cliffs (Fig. 9). A pine tree teeters precariously from the banks at the center of the composition, adding to the feeling of threatening unease, as if the viewer might tumble into the roiling waters along with the tree. While the area around Niagara Falls had been developed and commercialized through the advancement of industry and tourism by the 1860s, Bierstadt shows no hint of these changes in his painting.

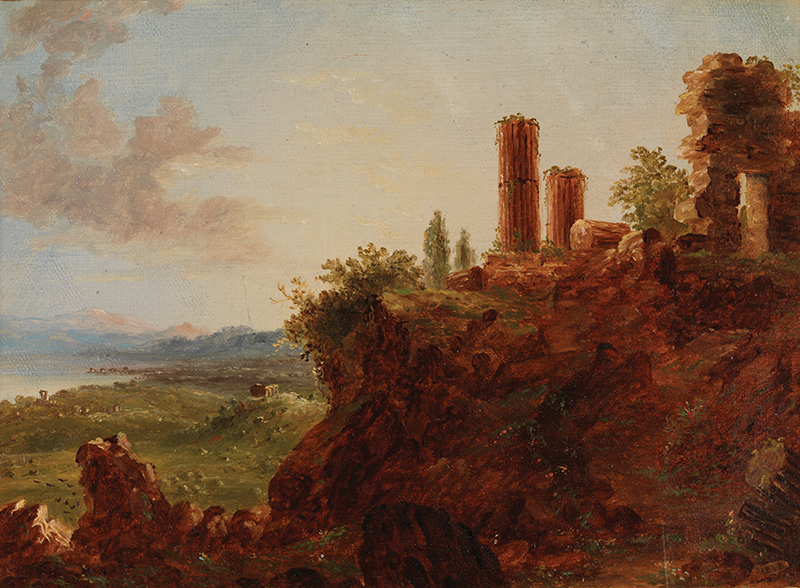

Hudson River school artists had begun to carry their interpretation of the landscape abroad in the 1840s and 1850s—Cole to Europe, Bierstadt and Thomas Moran and others to the new frontier of the American West, and Frederic Edwin Church to South America. Since carrying oil paints and brushes out into the field was a burdensome process, Cole often preferred to sketch in pencil, making his surviving plein-air oil sketches fairly rare, though they are crafted to capture the overall effects and forms of a landscape and only infrequently correlate directly to a particular finished canvas. Cole painted View of Sicily (Fig. 6) around the time of his 1842 visit to the island, and it is representative of his style of recording the fleeting details of light and color in outdoor sketches before returning to his studio to craft his finished paintings.

Church’s career would be largely defined by his travels. Following explorer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt’s call for artists to travel to South America and paint its tropical landscapes, Church visited the continent twice, in 1853 and 1857, trekking through Panama, Ecuador, and Colombia, making notes and sketches that inspired major studio paintings like Valley of Santa Ysabel, New Granada (Fig. 11)—employing the name by which the northwestern corner of the continent had been known. Church’s vision of South America is Edenic, a tranquil scene suffused in warm light and lush greenery, with a masterfully rendered atmosphere that conveys the heat and humidity of thick equatorial air. His is a reverent depiction of the power and scale of landscape, eliding all signs of human progress and industrialization that were sweeping the continent by 1875, as well as the devastation wrought by a powerful earthquake that year on the border of present-day Venezuela and Colombia—an event that may have inspired him to paint this elegiac canvas. It was the first painting by Church to enter the Pennsylvania Academy collection, and it is housed in its original frame, designed by the artist, with Moorish-inspired details alluding to other travels abroad that deeply influenced his aesthetic visions, namely his 1860s visit to the Middle East.

Yet the American scene never lost its allure for these artists. Before he went west and immortalized the landscape of Yellowstone, back in Philadelphia Thomas Moran painted a series of views illustrating the scenic beauties of the newly expanding Fairmount Park. While some in the city advocated hiring landscape architects to modernize and streamline the park, the park’s Committee on Plans and Improvements argued that “No other city in the Union has, within its boundaries, streams which, in picturesque and romantic beauty, can compare with the Wissahickon and the Schuylkill; and there are few, if any, which include within their limits landscapes, which, in sylvan grace and beauty, surpass those which abound within the space we propose to appropriate.” In Two Women in the Woods, from 1870, Moran features one of the park’s sylvan paths, today known as Forbidden Drive, which runs alongside the Wissahickon (Fig. 8).

A similarly beautiful swath along the Hudson was painted in the same year by David Johnson (Fig. 10). Here, Johnson takes an elevated view looking northward on the river toward West Point, letting the grandeur and expanse of the valley below create the composition’s greatest impact. Close looking is rewarded by the discovery of numerous vignettes—people and animals, trains and steamships, winding paths and stone walls—that demonstrate his ability to nest detailed scenes of a pastoral human existence in a unified panoramic view of nature. Johnson’s deference to painstaking verisimilitude is a consistent theme across his career on both small and large canvasses, even when the taste for this type of landscape painting waned in the 1870s.

In the Pennsylvania Academy’s current exhibition, Edmund Darch Lewis’s commemoration of the 1876 Centennial Exhibition on the banks of the Schuyl-kill River brings the early republic’s landscape painting traditions full circle (Fig. 12). Lewis depicts the Schuylkill on a grand scale as a majestic natural element, like Church’s panoramas of South America or Bierstadt’s sublime images of Niagara Falls, rather than just a site in service to human tourism, commerce, and urban development. One hundred years after independence was declared in Philadelphia, the enterprise of defining the American landscape for a new national identity had traveled from the Schuylkill River up to the Hudson, and returned home as changed as the country it visualized.

From the Schuylkill to the Hudson: Landscapes of the Early American Republic is on view at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts to December 29.

1 Bruce Robertson, “Venit, Vidit, Depinxit: The Military Artist in America,” in Edward J. Nygren and Bruce Robertson, Views and Visions: American Landscape Before 1830 (Washington, DC: Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1986), pp. 83–103. See also Jeremy Elwell Adamson, Niagara: Two Centuries of Changing Attitudes, 1697–1901 (Washington, DC: Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1985), pp. 20–22. 2 William Dunlap, History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States (New York: George P. Scott & Co., 1834), vol. 2, p. 359. Also cited in Kenneth Myers, The Catskills: Painters, Writers, and Tourists in the Mountains, 1820–1895 (Yonkers, NY: Hudson River Museum of Westchester, 1988), p. 125. 3 First Annual Report of the Commissioners of Fairmount Park (Philadelphia: King & Baird, 1869), p. 29.

ANNA O. MARLEY is curator of historical American art and director of the Center for the Study of the American Artist at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.