Fig. 1. Red Ascension by Betye Saar (1926–), 2011. Signed and dated “Betye Saar 2011.” Mixed-media assemblage; height 17 ½, length 96 ½, depth 3 ¼ inches. Except as noted, all images courtesy the artist and Roberts & Tilton, Los Angeles; photograph by Robert Wedemeyer.

For more than half a century Betye Saar has lived on a tree-shaded hill in Laurel Canyon, high above the glitz and glam of Hollywood, in a rustic 1920s home that neighbors a log cabin that once belonged to rocker Frank Zappa. Every day before she descends the hill to the art studio on her property, the Los Angeles-born icon of assemblage art goes out to the street to grab her mail. Those strolls often produce the ideas that inform her densely layered works, which are not so much sculptures as three-dimensional collages. “Sometimes a color will give me a clue about what I want to make. Sometimes I will put everything I think is appropriate in a pile that is blue or red,” Saar says, explaining the way she sorts the objects—candles, bottles, organic wooden forms, including one in the shape of a starfish—she uses in her creations. “This time it’s dark brown and black. This is how I work. It’s always in motion in a way and [the art] develops in the motion.”

Fig. 2. The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, 1972. Mixed-media assemblage; height 11 ¾, width 8, depth 2 ¾ inches. Berkeley Art Museum, California; purchased with the aid of funds from the National Endowment for the Arts (selected by the Committee for the Acquisition of Afro-American Art).

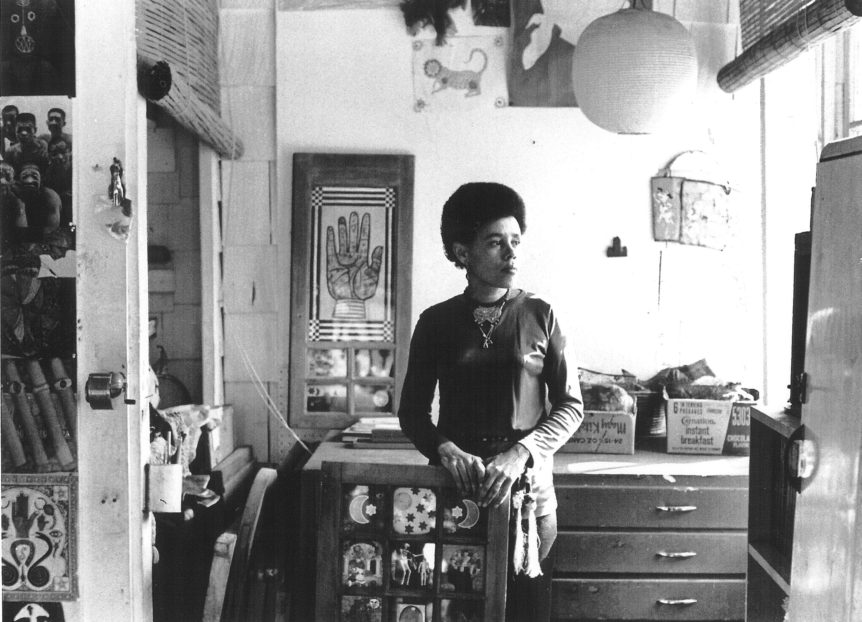

Fig. 3. Saar in her studio, 2015. Photograph by Ashley Walker.

Though she travels far less than she used to, at ninety-one the artist remains very much in motion these days, amid a whirl of late-career exhibitions in venues that stretch from LA to Milan. Last winter she was the subject of a wide-ranging, fifty-year survey at Milan’s Fondazione Prada; this spring a selection of her sculptures anchored two powerful group shows in Los Angeles featuring the work of black female artists. This summer she’s part of exhibitions at Tate Modern and the Brooklyn Museum, while twenty-two of her politically charged, washboard-based assemblages dating back to the late ’90s are the focus of Betye Saar: Keepin’ It Clean, on view through August 20 at the Craft and Folk Art Museum on Wilshire Boulevard. On a sunny May afternoon she’s busy in her studio organizing elements for a room-size installation that will be unveiled next January at her LA gallery, Roberts & Tilton.

Though many inspirations sparked Saar’s long career in the arts, two—experienced decades apart—stand out from the rest. The first came as a child, watching Simon Rodia build the Watts Towers, the soaring spires of rebar, concrete, and ceramic and glass fragments in South Central LA. Saar grew up to take a degree in design from UCLA in 1949, and went on to make enameled jewelry and to design greeting cards. After post-graduate studies in printmaking, in the early 1960s Saar began what she calls her “flat work” in mediums such as intaglio and collage. Then, in 1967, she had a second revelation: she saw Joseph Cornell’s intimately scaled, often surreal boxed assemblages at the Pasadena Art Museum (now the Norton Simon Museum). From Cornell and Rodia, Saar learned the power of disparate objects—especially found objects—given a context.

Fig. 4. Saar in her Los Angeles studio with Black Girl’s Window, in a photograph by Robert A. Nakamura, 1970. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

One of the first contextualizing tools Saar employed was an empty mullioned window frame. “I started out putting prints in windows and I would nail things on the frame of the window and [the art] just developed very organically,” she says. Her seminal work from this period, Black Girl’s Window (1969)—a self-portrait surrounded by symbols from a personal cosmology—is now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. “When you’re a designer,” she says, “you’re always framing something.”

In many ways, Saar’s entire oeuvre—from the windows, which she still makes, to her monochromatic room-size installations—can be seen as a framing device for the “sacred elements,” as she calls them, that energize her works. Bits of chain, bones, shells, teeth, birdcages, sailing ship forms, blackbird-shaped pieces, and other objects sit catalogued in and around numerous neatly organized tables, bins, and shelves in her sun-filled studio. In Saar’s hands, such common items take on a powerful emotional and political resonance. “Part of living in Laurel Canyon was being a collector,” says artist Alison Saar, the middle of Betye’s three daughters, who is participating in a threeperson show with her mother and her older sister, Lezley Saar, in January at the Lancaster Museum of Art and History, in California. “We would all go to the Rose Bowl Flea Market and estate sales, but it wasn’t like we had a shopping list. [My mother] would just gather anything that was intriguing to her that she thought she could incorporate into her work.”

Fig. 5. Black Girl’s Window, 1969. Mixed-media assemblage in window; height 35 ¾, width 18 inches. Museum of Modern Art, Modern Women’s Fund and Committee on Painting and Sculpture Funds.

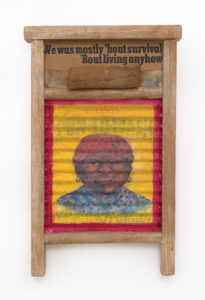

“Usually I collect things for two or three years before they become art objects,” says Betye Saar. Of the washboards central to her work in the show at the Craft and Folk Art Museum, she explains: “I just liked the way the washboard looked; my grandmother had one. I like the sentiment that’s attached. It’s for labor, but it’s also for cleanliness. So I feel that by recycling the washboard I’m paying homage to the working woman, especially the ancestral working woman, as well as the slave woman and the housewives and homemakers.”

- Fig. 6. Mti, 1973. Mixed- media assemblage; height 42 ½, width 23 ½, depth 17 ½ inches.

- Fig. 8. Record for Hattie, 1975. Mixed-media assemblage; height 14, width 13 ½, depth 2 inches. Private collection.

A consistent theme in Saar’s work has been the subversion of the racial caricatures in advertising ephemera and early twentieth-century knickknacks and other tchotchkes she collects. In one of her best known and most provocative works, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (Fig. 2), she recast the demeaning mammy stereotype as a guerrilla, armed with a rifle. “Instead of being a servant or a slave, I made her a revolutionary,” Saar says.

Fig. 7. We Was Mostly ’Bout Survival, 2017. Mixed-media assemblage; height 37, width 8 ½, depth 2 ¾ inches.

That caricature appears in several of the washboard assemblages shown at the Craft and Folk Art Museum, paired with clocks to suggest that while time may be moving forward, our society is standing still. More recent washboards in the exhibition incorporate found images of black male musicians and boys as a response to the Black Lives Matter movement. “Racism hasn’t changed, racism has not gone away, it’s still here,” says Saar. “When I started this series there was a rash of police brutality and a lot of younger and older men were just shot to death. You couldn’t pick up a paper without reading about some black man being killed just getting out of his car.”

- Fig. 9. Dubl Handi (Red), 1998–2014. Mixed media on vintage washboard; height 21 ½, width 8 ¾ inches.

- Fig. 11. Extreme Times Call for Extreme Heroines, 2017. Mixed media on vintage washboard; height 21 ½, width 8 ⅝ inches.

- Fig. 12. We Was Mostly ’Bout Survival, ’Bout Livin’ Anyhow, 2017. Mixed media on vintage washboard; height 13, width 8 inches.

But some see a sense of hope in Saar’s washboard pieces, manifested in her choice of materials. “In a wash cycle there are different stages you have to go through to get dirty clothes clean,” says curator Holly Jerger of the Craft and Folk Art Museum. “We see that as a metaphor for America itself coming to terms with and acknowledging its history of racism and sexism and classism and how we can move forward from that.”

Fig. 10. The Weight of Betrayal, 2015. Mixedmedia assemblage; height 32 ½, width 15 ½, depth 10 inches.

Fig. 13. Installation view of Betye Saar: Uneasy Dancer at the Fondazione Prada, Milan, September 15, 2016–January 8, 2017. Photograph by Roberto Marossi; courtesy Fondazione Prada.

Michael Slenske is a Los Angeles–based writer and editor who covers art, culture, and travel. He is editor-at-large of LALA and Cultured and a contributing editor at Modern Painters. His work also appears in W, Architectural Digest, WSJ, Wallpaper, and DesignLA.