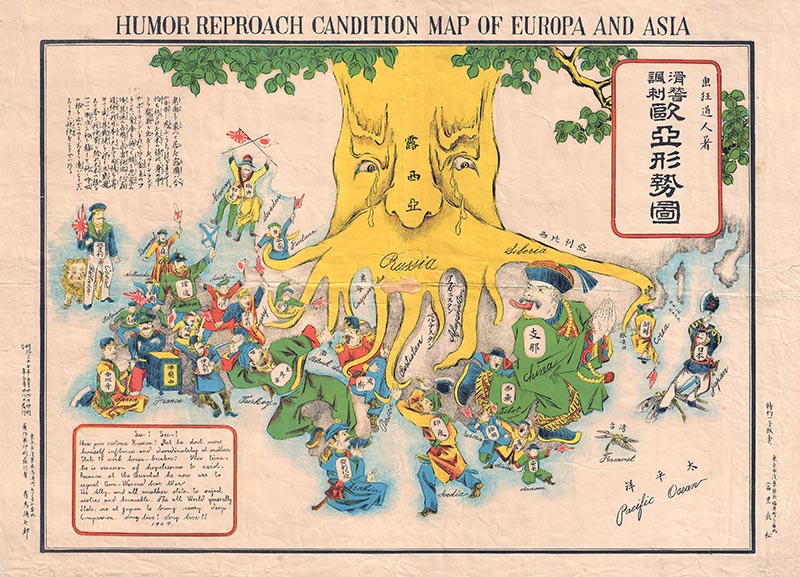

In this episode of Curious Objects, Benjamin Miller stops by the shop of his mentor Kevin Brown, founder of Geographicus Rare Antique Maps, to peruse a monumental Qing-era map of China and its environs. Created using a traditional Chinese rubbing technique, the richly-detailed blue and cyan map depicts the Qing Dynasty’s vast tribute system, a network of cities, tribes, and nations that extended as far as Europe . . . which is depicted as a tiny continent squeezed onto the margins. “This map isn’t really a map as it would be understood from a Western or European mindset,” Brown says. “It’s not printed or designed on a scale of distance—it’s on a scale of significance to the Qing emperor.” What good is a map that can’t get you from point A to point B? Listen in for answers to that question and more.

Kevin Brown: Like many people in the ’70s I had a large collection of Smurfs, which I sold on eBay. And some of them were selling for shocking amounts of money: hundreds—some of them in the multiple-hundreds—of dollars each. And it was enough for awhile for me to make my way in the world.

Benjamin Miller: By selling collectibles on eBay?

Kevin Brown: By selling Smurfs on eBay, mostly.

Benjamin Miller: Hello and welcome to Curious Objects & the stories behind them, brought to you by The Magazine ANTIQUES. I’m your host, Ben Miller.

First, I’d like to thank our sponsors, Freeman’s auction house and Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

Our first sponsor is Freeman’s auction house in Center City, Philadelphia. Whether you’re collecting or consigning, you want to deal with an auction house with a sterling reputation. Try Freeman’s! Freeman’s is the oldest auction house in America, dating to 1805. In my day job I deal in silver and jewelry, and we’ve bought dozens of pieces at Freeman’s, which ranged in value from a few hundred to tens of thousands of dollars. But it’s not just silver and jewelry—their specialists offer one-on-one service and expertise across all areas. Freeman’s specialists have worked with generations of private collectors, institutions, advisors, estates, and museums. Their spring sale season this year offered fourteen successful auctions, including eight significant private collections and four world auction records. Upcoming fall and winter auctions include an impressive list of subjects: Asian Arts, Fine Jewelry, Books, Maps & Manuscripts, Americana, British & European Furniture and Decorative Arts, as well as 20th century Design, and American Art & Pennsylvania Impressionists. Freeman’s is inviting new consignments right now. Want to find out more? Go to freemansauction.com.

Before we get started, I want to give a quick shout-out to the #mycuriousobject Instagram campaign. Last episode I mentioned that The Magazine ANTIQUES was launching a campaign to ask you all to post your own curious objects to Instagram. We’re going to pick a few of these pieces and feature them in the podcast! I’ve been honestly so impressed at not just the number of posts you’ve made but also at how interesting and even downright bizarre the objects have been. And it’s not too late to participate. Post a picture of your curious object to Instagram with the hashtag #mycuriousobject and tag The Magazine ANTIQUES (their handle is @antiquesmag). You can also tag me directly: my handle is @objectiveinterest. I can’t wait to see your objects! Again, that’s #mycuriousobject, tag @antiquesmag and @objectiveinterest.

Ok. My guest today is the owner of Geographicus Rare Antique Maps. His name is Kevin Brown. Kevin was actually the very first person I ever worked with in the antiques industry. I had a longstanding interest in maps, and Kevin and I are both in Brooklyn, and so before I even knew I wanted to be an antiques dealer, I did a little research for Kevin and he gave me my first introduction to the world of buying and selling antiques.

大清万年一统天下全图 [All-Under-Heaven Complete Map of the Everlasting Unified Qing Empire], 1811. Ink on paper, 55 by 98 inches. Courtesy of Geographicus Rare Antique Maps</em.

And, as always, you can find images of today’s curious object and related materials at themagazineantiques.com/podcast.

Today we’re talking about a two-hundred-year-old Chinese map that challenges some of the basic ideas about what a map is supposed to represent and achieve. Kevin is fastidious about his research and I think you’ll enjoy learning about this map. He also talked with me about his own very unusual start into the antiques business—as you might have guessed from the Smurfs in the intro quote—but we also managed to touch on such disparate subjects as Amazonian tribes and Donald Rumsfeld. So, with that teaser, I hope you’re excited to hear from Kevin Brown!

Benjamin Miller: So, Kevin Brown, thanks for joining me on the podcast.

Kevin Brown: Thank you. pleasure.

Benjamin Miller: Now, you’re a dealer in rare and antique maps. And that is such an overwhelmingly large field because there are maps from all periods from all parts of the world. There are real maps and imaginary maps, there are maps that show places and maps that show ideas. What kind of map do you typically deal in?

Kevin Brown: Well, we are, in fact, generalists. So, you’re right, we throw a wide net. Our earliest maps date to the 1400s, our most recent maps probably date to as late as, say, 1970 or so. In general, they are rare maps, so, as part of our moniker . . . our business name is accurate. So, we do focus on unusual, rare items. It’s more what we don’t do than what we do do.

“At Geographicus Rare Antique Maps we’re generalists. Our earliest maps date to the 1400s, our most recent maps probably date to as late as, say, 1970 or so.”

Benjamin Miller: So, like jazz.

Kevin Brown: I suppose! So, we don’t compete excessively with the European market, so, you won’t find our site full of maps of different provinces in France, English counties, or German provinces. We do have a strong European content but it’s more general than that. So, we might have a map of Italy but not a map of Florence . . . although we do have maps of Florence.

Benjamin Miller: But maybe no, you know, “The Second Day of the Battle of Waterloo” or . . .

Kevin Brown: No. Something like that we probably would not have. We also don’t generally have a strong content in South America. Otherwise, we get everything.

Benjamin Miller: And the map that I wanted to talk to you about today is a map of . . . well, it’s a map of China, but it’s kind of also a map of the world. And I find this thing completely fascinating and . . . not to mention visually very impressive. So, let’s dive into talking about this Qing Dynasty map. And I should say for listeners [that] the scale of this thing is massive. I mean, it’s . . . What is it, four feet by six feet or?

Kevin Brown: It’s about fifty-five by ninety-eight inches. This is an expansive map. It was issued in 1811 in China and as we mentioned it’s about ninety-eight inches wide which for a map is quite large. It’s meant to cover an entire wall or, as it may have appeared in China, on a screen. It is often called “printed in negative,” although that is not precisely true. But the map is a striking, resonant deep blue and the seas around it are a lighter, almost iridescent blue. And color was very, very significant in Chinese . . . not only social and political thinking but also mystical thinking. The blue is . . . somewhat obvious . . . the Chinese character for blue (at least the color blue that’s used here) is in fact the same as the character that is part of the term “Qing.”

“This map was issued in 1811 in China and it’s about ninety-eight inches wide. The blue color is very significant: the Chinese character for blue is the same character that forms part of the term ‘Qing,’ for ‘the Qing Dynasty.”

Benjamin Miller: Oh, really? I had no idea.

Kevin Brown: And, so . . . or at least “Great Qing.” So, there’s probably a bit of a play going on that the artisan would have been aware of when choosing to make it in this intense color combination.

Benjamin Miller: So, was blue an important color for the Qing Dynasty more generally?

Kevin Brown: Yes. So, in traditional Chinese iconography, blue references immortality, underscoring the everlasting nature of the Qing empire, which is in fact part of the title of the map in translation.

Benjamin Miller: Oh, I didn’t realize it had a title!

Kevin Brown: It does. The translation of the title would be “All-Under-Heaven Complete Map of the Everlasting Unified Qing Empire.”

Benjamin Miller: Oh, is that all? that’s quite an ambitious headline.

“The translation of the map’s title is ‘All-Under-Heaven Complete Map of the Everlasting Unified Qing Empire.’ This was an administrative map. If you were the emperor, you would look at this map to understand the tax and tribute system throughout your entire empire.”

Kevin Brown: Yes, well, it was made for the emperor. And, of course, the mapmaker would have wanted the emperor to be impressed with the map. So . . . and all of the geographical features and annotations . . . appear in white. So, it is extremely vibrant and striking to observe.

Benjamin Miller: And you can see, of course, land and sea, and you can see some geographical features. There are quite a few rivers including a couple of prominent rivers. Are those the Yangtze and the Yellow River?

Kevin Brown: That’s right, the two dominant rivers that flow through the map are the Yangtze and the Yellow River, which are gigantic snake-like white bands that run deep into the map.

Benjamin Miller: But the overwhelming feature over the surface of the map is actually Chinese characters.

Kevin Brown: Well, yes, and symbols. This was an administrative map if it could be called anything. And, so, as such, if it was made for the emperor and if you were the emperor you would look at this map and by looking at it you would understand the tax and tribute system throughout your entire empire. And, notably, there are no borders. The Qing saw their domain as extending everywhere where tribute was paid to them, and various kinds of tributes flowed into the empire from various sorts of officials, magistrates, foreign embassies, etc., etc. . . . So, if someone had brought a tribute to the emperor their country is most likely represented on this map. So, there are quite a few countries on the map that . . . from when you’re initially looking at it you would not suspect. Nor is this map really a map as it would be understood from the Western or European mindset. So, it’s not printed or designed on a scale of distance, it’s on a scale of significance to the Qing emperor.

“This isn’t really a map in the Western or European sense of the word. It’s not designed on a scale of distance, but on a scale of significance to the Qing emperor.”

Benjamin Miller: So, tell me a bit about the representations of lands outside of China. Because we have the Yangtze and the Yellow Rivers running across . . . really, the majority of the map, and then all of what appears to be Africa and Europe condensed into a very small . . . almost a margin, on the left side. Is it clear or is it delineated exactly what regions of the rest of the world are represented?

Kevin Brown: Somewhat. The map includes, definitely, England, includes Holland, includes Southeast Asia and Africa. There’s a possibility that it also includes Portugal but some of the terminology is unclear. So, the map uses extremely Chinese, if you will, terminology to describe various places. Holland is “the land of red beards” and Portugal is “the land of the great western sea.” Italy is possibly on it; the Atlantic itself is “the great western sea.” Arabia appears on the map as “the homeland of Islam,” and—

Detail of 大清万年一统天下全图 [All-Under-Heaven Complete Map of the Everlasting Unified Qing Empire], 1811. Courtesy of Geographicus Rare Antique Maps.

Kevin Brown: It is, yes. And Africa, curiously, has an interesting term: “the land of black ghost.”

Benjamin Miller: “Black ghost”?

Kevin Brown: “Black ghosts.” What they actually meant by this is not 100 percent clear, but—

Benjamin Miller: I’m sure whatever it was is terribly politically incorrect.

Kevin Brown: I’m sure, I’m sure. Or maybe not. Maybe it’s just an odd translation or an archaic usage that doesn’t apply today.

“The map includes England, Holland, Southeast Asia, and Africa. Holland is labeled as ‘the land of red beards,’ Portugal is ‘the land of the great western sea,’ Arabia is ‘the homeland of Islam.'”

Benjamin Miller: Ok. So, it’s interesting to me that you describe it as an administrative map and I would typically think that an administrative map would . . . you would want it to be accurate in some sense. You would want it to be useful as a representation of the distances between places. And if you look at European maps in this time period, they’re arriving at the point of being quite accurate from the perspective of representing the physical shape and size of bodies of land and water. This map is not like that. As you say, the proportions are representative not of physical scale but of political prominence. What use was that, really? What good was it to have a map that showed the world not as it exists physically but as it exists from a kind of egocentric perspective?

Kevin Brown: Well, you have to start with the basic understanding that the Qing were a nomadic warrior people, and—

Benjamin Miller: They were the Manchus from north China?

Kevin Brown: Correct, yes. So, they did not see themselves bound or limited by physical barriers or distances in the way that a European king may have considered their empire. So, the Qing really didn’t care how far it extended or how big it was. They cared that it was big, but it was more about the tributes that came in. And, so, the map . . . if you look at it with detail and care there are little symbols on it, there are circles and squares and squares with triangles over it and diamonds and other symbols. All these refer to various functionaries within the empire that would deliver a different kind of tribute. So, some symbols might represent a major city. Others might represent a regional sub-magistrate. Others might represent an indigenous chieftain or something who pays tribute to the emperor. So, when the emperor looked at this, what he saw is he saw his tax income. He’s like “Oh, I’m receiving a certain level of tax from this regional magistrate in Guangzhou province. Good!” And, so, he was able to see the extent of his empire, he was able to see where the money was coming from, where it was coming from. He perhaps might say, “Well, I think we can get more money out of this area over here. Send out the armies.” Or, more likely, “send out a million Han settlers to repopulate this region and develop it so that I will have more—

Benjamin Miller: And fill it with our culture and our populace.

“There are no borders on the map. The Qing were a nomadic warrior people, and they did not see themselves bound or limited by physical barriers or distances in the way that a European king may have considered his empire.”

Kevin Brown: —income from the region.” And, in fact, potentially one of the reasons that this map was made in 1811 was because of a massive resettlement of Han Chinese farther to the west that redistributed the wealth of the empire.

Benjamin Miller: Oh, I see. So, tell me about the history of this particular map, because it was issued in 1811 but that wasn’t the first printing of this map, right?

Kevin Brown: No. So, this is part of a series of maps called the “Tianxia Quantu.” They are based upon the cartography of a fellow named Huang Zongxi. That pronunciation may be a little bit off, but, uh—

Benjamin Miller: I’m certainly not going to correct you.

“It’s possible that this map was made in 1811 because there was a massive resettlement of Han Chinese farther to the west that redistributed the wealth of the empire. . . . or it may have been created that year because of the suppression of several rebellions.”

Kevin Brown: Thank you. It’s close. And he initially made the map sometime in the late 1600s. That map is lost. We have no record of it. It has not survived. The earliest example was probably produced by his son. And the earliest known example is a manuscript version of the map that is held in the national archives in China and that dates to 1800. Now, after—

Benjamin Miller: By “manuscript version,” you mean it was drawn by hand?

Kevin Brown: That’s right, it’s hand-drawn. After that, printed versions start appearing and they would be reissued at various times—significant points in the empire’s history. This map . . . it’s not 100 percent clear why it was issued in 1811. It may have been because of the massive redistribution of Han Chinese that we mentioned earlier, it may have been because of the suppression of several rebellions which occurred in that year. It’s not clear, but, in general, it was not the best year for the Qing, but they did issue this map in that year. And this is the only example of it to be issued, as people say, in negative. And, in fact, it’s not really issued in negative, it’s a rubbing. It’s not a printing. It’s a rubbing, which is a Chinese process, very traditional. Large pieces of cloth in strips will be laid down on a stone block and it’d be wetted and then the inks would be applied with a pounding ink block and that yielded the intense blue and in fact the white areas are not printed areas, rather, they [indicate] lack of printing, and so that gives it the intense physical and visual appearance that it has.

Benjamin Miller: So, the white areas would have been carved out of the base stone . . .

Kevin Brown: That’s right.

Benjamin Miller: . . . so the ink would not have shown up on those spots.

Kevin Brown: That’s exactly right.

“This is part of a series of maps called the ‘Tianxia Quantu,’ which were based upon the cartography of a fellow named Huang Zongxi. This map isn’t a printing. It’s a rubbing, which is a very traditional Chinese process that gives it the intense physical and visual appearance that it has.”

Benjamin Miller: I want to dwell a little more on the political significance of it. Would copies of this map have also been used as propaganda material or as decorative works or would there have been other purposes besides the emperor sitting around on his settee and gloating over the amount of taxes coming in from various provinces?

Kevin Brown: It’s not clear how distributed it was within China at the time it was probably maintained mostly within the central governance circles.

Benjamin Miller: Did Chinese mapmaking change dramatically when the Qing took power? As you say, they were a nomadic people, they might have had a different idea of what a map represents and how it ought to be oriented. Are earlier Chinese maps more representational?

Kevin Brown: Well, like many things related to China, especially the historical development of China and technology, it is incredible how complex and advanced Chinese cartography actually was by any measure. So, we have maps dating—well, we don’t have them, but we are aware . . . there are historical references and examples of maps dating into extreme antiquity that are mind-bogglingly accurate on a rigid grid system. They show detailed descriptions of all of the rivers and waterways throughout China. And so these exist. So, when you ask, “Did the Qing change the way the Chinese saw their empire?”—potentially. Or, potentially, the map . . . mapping of China simply changed to suit their own vision of the world. The model that this map has, however, where distant provinces and kingdoms and empires are represented in a minor, tiny scale, as kind of a minutiae at the border of the map—that is a common theme through Chinese maps from the 1600s all the way up into the early nineteenth century, or, I would say, mid-nineteenth century when greater exposure to European maps changed the outlook somewhat. There are also other interesting Chinese maps that exist and that we know of. For example, there is the Selden map, which was probably made for a merchant. And in contrast to almost all other Chinese maps is actually a fairly accurate map showing Chinese . . . the Chinese coast and all of southeast Asia down through Malaysia and part of the East India Islands. So, it defies, in a sense, this kind of cartography. It shows that there’s a lot more there than we’re clearly aware of and there is . . . the Chinese had a great deal of awareness of the world around them that didn’t necessarily manifest itself clearly in maps as we understand them in the Western world.

“It is incredible how complex and advanced Chinese cartography actually was. There are historical references to, and examples of, maps dating into extreme antiquity that are mind-bogglingly accurate on a rigid grid system. . . . The Chinese had a great deal of awareness of the world around them that didn’t necessarily manifest itself clearly in maps as we understand them in the Western world.”

Benjamin Miller: We’re going to take a short break before hearing from Kevin about his truly off-the-beaten-path entrée into the business of antique map–dealing. As usual, I want to take a minute to thank you sincerely for listening. If you enjoy the podcast and want to help us reach more people, the easiest thing to do is leave a rating and review on iTunes. And if you have a friend or colleague who maybe watches Storage Wars or Antiques Roadshow, clue them in to Curious Objects! I’m so grateful to you for helping to spread the word. I’m also grateful for your feedback, and I’ve been receiving some really great, helpful comments lately. As always you can email me at podcast@themagazineantiques.com, and you can also find me on Instagram @objectiveinterest. Give me your thoughts, your ideas for future guests—I really do want to hear it all!

Our second sponsor for this episode is Reynolda House Museum of American Art in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Reynolda House is more than just an elegant 1917 historic estate. It’s also home to a compelling and surprisingly wide-ranging collection of fine and decorative arts. Now, if you listen to this podcast, you probably already like house museums. But Reynolda House goes beyond the typical displays of period furniture and old portraits. When you visit, you’ll find thought-provoking objects like American artist Martin Johnson Heade’s most famous orchid and hummingbird painting, tobacco baron R. J. Reynolds’s mink coat, and century-old farm buildings now serving crepes and rosé. That’s going to be an important part of my visit! They also have a brand-new app you can download called Reynolda Revealed, which takes you on a virtual tour of the museum and grounds. I downloaded it on my phone, and, I have to say, it’s actually a lot of fun to play around with and see all the photos and backstories. I highly recommend checking it out at reynolda.org, and, of course, planning your visit to the house in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. That’s r-e-y-n-o-l-d-a.org.

Detail of 大清万年一统天下全图 [All-Under-Heaven Complete Map of the Everlasting Unified Qing Empire], 1811. Courtesy of Geographicus Rare Antique Maps.

Kevin Brown: I suppose I graduated from college with degrees in philosophy and history with a focus in medieval pilgrimage. I had a bias against earning money.

Benjamin Miller: I’m sorry, you had a focus in medieval pilgrimage?

Kevin Brown: I did. So, it’s not unrelated to maps! I focused on the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, which I hiked twice as part of my academic research.

Benjamin Miller: Ah, my sister finished that two days ago.

Kevin Brown: Ah! Well, congratulations! It’s an incredible experience, and part of that was seeing the world in a different way, thinking about your life and what your values are. And my own values, I quickly decided that, would not allow me to work for money. They would allow me to earn money—of course, everyone needs to earn money—but not for my time. I was willing to sell my knowledge, my experience, but I was not willing to sell my time. Unfortunately, with degrees in philosophy and history I did not have marketable knowledge or experience.

Benjamin Miller: I’ve been there.

Kevin Brown: But, nonetheless, we progress. And I moved to New York City and was staying with a friend. And I’m . . . eBay at the time was just getting rolling. It was very early on in eBay’s history, and a lot of things—

Benjamin Miller: This is what, late ’90s?

Kevin Brown: I would say early ’90s. eBay was just getting rolling and a lot of things happened with eBay at that point: things that were not really rare attained a fairly high value because there was a perception of rarity. For example, as a child, like many people in the ’70s I had a large collection of Smurfs, which I sold on eBay. And some of them were selling for shocking amounts of money, some of them, you know, in the multiple hundreds of dollars each. And it was enough—for awhile—for me to make my way in the world.

“Like many children in the ’70s I had a large collection of Smurfs, which I sold on eBay. And some of them were selling for shocking amounts of money. And it was enough—for awhile—for me to make my way in the world.”

Benjamin Miller: So, you were paying your rent by selling collectibles on eBay.

Kevin Brown: Selling Smurfs on eBay, mostly. My childhood toys. Then it occurred to me that I needed to resupply, and I would hit flea markets, drive up to Connecticut and anywhere I could, look for odds and ends that I could sell. And I did ok with that and paid some bills. But I certainly wasn’t getting rich and when my housing situation went downhill, through—

Benjamin Miller: As it does in New York.

Kevin Brown: As it does. I found myself in rather dire straits. I did not have an established income. I had a lot of experience in the world that did not qualify me to become a burger and fries chef at McDonalds, and I had rather high aspirations for my lifestyle. So that . . . all of these were rather problematic. But I saw an alternative: It was better to burn out than fade away. So, I went to Venezuela, which at the time was the cheapest place to fly to in South America, and I had this vision that I was going to live with indigenous tribes.

Benjamin Miller: Wow.

Kevin Brown: And just have a different kind of nonmonetary lifestyle. So, I worked my way to the southern reaches of Amazonas province in Venezuela and I did meet some tribes and I did briefly stay with them but I pretty early on figured out that the tribal lifestyle was not for me.

Benjamin Miller: What was it that tipped you off to that?

Kevin Brown: There were a lot of details that are probably not appropriate for a podcast, so I’ll pass on that question if you don’t mind.

Benjamin Miller: Ok, fair enough.

Kevin Brown: But, nonetheless, a few weeks later I packed up my bags and I was returning home to New York City. At the time, I was staying with a friend and I put all of these items on eBay, which is something I knew how to do. And not all of them, most of them. And one fellow bought them who happened to live very close to where I was staying. I dropped them off at his place and he was a prominent tribal art dealer and called me a few weeks later and he said, “Well, Kevin, you know, I appreciate the things you sold me, but I really wasn’t interested in them, I was interested in meeting someone like you who has an interest in this kind of work and travel. I’m old. I have a sickness that’s making life very difficult for me, but I would like to stay in the business and I kind of need someone to be my legs and to pick up where I can’t leave off, and in turn I’ll introduce you to this incredible business that will be a great way of life.”

Benjamin Miller: Wow.

“When I got back to New York, a prominent tribal art dealer introduced me to buying and selling at auction and helped me to learn pretty much everything that I knew when I started the antique map business.”

Kevin Brown: So, he introduced me to buying and selling at auction, to the higher levels of the art and antiques market. He was a great person. He helped me learn pretty much everything that I knew when I started the antique map business. So, when he finally decided that he wanted to wind things down, I decided also that I was not going to be a tribal art dealer. And, in the meantime, I had built up a small collection of antique maps, which had always been something that I gravitated to and said that this would be where I wanted to go and how I wanted to develop myself as a dealer.

Benjamin Miller: How old were you?

Kevin Brown: At this time, I was in my late twenties, and it’s been, it’s been going ever since then. Not that there haven’t been hard times. Being an antiques dealer’s hard. It’s very easy to become cash-strapped because it’s a cash-intensive business. You know, every day someone’s calling you and you want another . . . and offering you something you can’t refuse for fifty thousand dollars—

Benjamin Miller: Yep. Yep.

Kevin Brown: And you say “oh, boy!” But you build up your capital reserves, you build up your business, you build up your client base. So, eventually, you can grow your business in this way. It’s not an easy road, but it is a road that you can follow. And we did, and it turned out to do pretty well. We’re at this point fairly well-established, we’re one of the largest dealers in terms of volume of antique maps probably anywhere in the world, and we often get really exciting material that’s inspiring to find, and every day is a treasure hunt even if it’s a treasure hunt with your own inventory. And then, oftentimes, you know, you get to go out and travel the world and meet other dealers. There aren’t very many of us so we’re a close-knit group of . . . I would say friends, mostly. So, it’s a wonderful business.

Benjamin Miller: So, that’s a fascinating entrée into the field, and you’re in an enviable position now, but there’s a middle part that you wave your hands over a little, which is how you went from having a small collection of, you know, a personal collection of antique maps to having a really impressive inventory with objects like this Qing map of China. And that’s a process that I think for a lot of people who are considering a career in the antiques world is really intimidating because you have to not only find . . . you not only have to educate yourself about the material and become an expert and prepare yourself to make mistakes, but you also have to build up a clientele and find people who are willing to trust you and take a risk with you when you’re not yet very well-established.

“Being an antiques dealer’s hard. It’s very easy to become cash-strapped because it’s a cash-intensive business. Every day someone’s calling you and offering you something you can’t refuse for fifty thousand dollars. You have to stick with it. Grit. You sell something for less than you want to sell it for, but that allows you to buy something else. You try to find things in innovative ways.”

Kevin Brown: The middle ground—I did gloss over it, and it’s mostly because it’s not pretty, it’s hard. One should rightly be intimidated. I have . . . I remember times when my bank account was at zero. I would go for a month without making a single sale, I was broke. And yet, persistence with anything. You stick to it. Grit. You make it happen. You sell something for less than you want so you can buy something else so you can make money on it or just pay your rent. You find . . . you try to find things in innovative ways. Somebody once told me something which I liked a great deal and I think is quite smart. There are two things, actually, I can say that I think are quite smart, that helped us grow our businesses. One was . . . it was an accountant who I was working with told me this, and he was comparing me with the gentleman who introduced me to tribal art. What he said was, he said, “Well, he needs to make about seventy cents on every dollar. You need to make about five dollars on every dollar.”

Benjamin Miller: Yeah, yeah.

Detail of 大清万年一统天下全图 [All-Under-Heaven Complete Map of the Everlasting Unified Qing Empire], 1811. Courtesy of Geographicus Rare Antique Maps</em.

Benjamin Miller: [Known] unknowns, right.

“Recently I heard one of my clients use Rumsfeldian terms—’known known,’ ‘known unknown,’ and ‘unknown unknown’—to describe how he collects, and I realized that this is also how we buy.”

Kevin Brown: So, these are things that you know are out there, but you haven’t seen or found. This is a little more desirable. So, early on as a dealer I would not really focus on known knowns because everyone knows what it is and you’re not going to make that much money.

Benjamin Miller: Yeah.

Kevin Brown: Now, known unknowns. That’s great because you . . . if you have a lot of knowledge then you can say “Aha! I have . . . I know what this is and maybe this other person who’s selling it at a little antiques shop in Wichita doesn’t know what it is. You can buy it, you can mark it up, and you can make some money, you can introduce it to the market.

Benjamin Miller: And that’s an area where . . . not to sidetrack us, but it seems like the Internet is really kind of compressing what fits into that category because now that little dealer in Wichita might actually Google what he’s got and find out what it is.

Kevin Brown: Not might, will. They will Google it, but they won’t . . . this is why it’s a [known] unknown, right? So, they will, they will probably Google it. They will probably not find anything. So, the typical process if someone doesn’t know anything about a specialty item—they find it at maybe a picker, they buy at a house sale—they’ll Google it and if they find it, they’re like “Aha!” They’ll take the most expensive price they see online, and they’ll say, “Ok, that’s what I’m going to get for it and then they’ll start calling up everybody they could think of saying, “Hey, I got this, I’d be willing to sell it for 10 percent less than this most expensive price I’ve ever seen.” And then they quickly realize they’re not going to sell it. And the other thing that happens is they Google it and they find absolutely nothing and they’re like “Oh, it’s a piece of junk! No one knows anything about it.” And they put a price of whatever their gut instinct is, and it could be outrageously high, or it could be outrageously low. And then going back to the Rumsfeldian argument, there’s the “unknown unknowns” and these are just things that you stumble across that nobody knows about, no one knows what they are, and you have to figure out what they are. And through experience and instinct and knowledge and historical information and comparable data that you might have in the back of your mind, maybe you can figure out what it is or at least place it as something that may have value, and then you can buy something and you can probably make good money.

Benjamin Miller: Can you give me an example of a sexy unknown unknown?

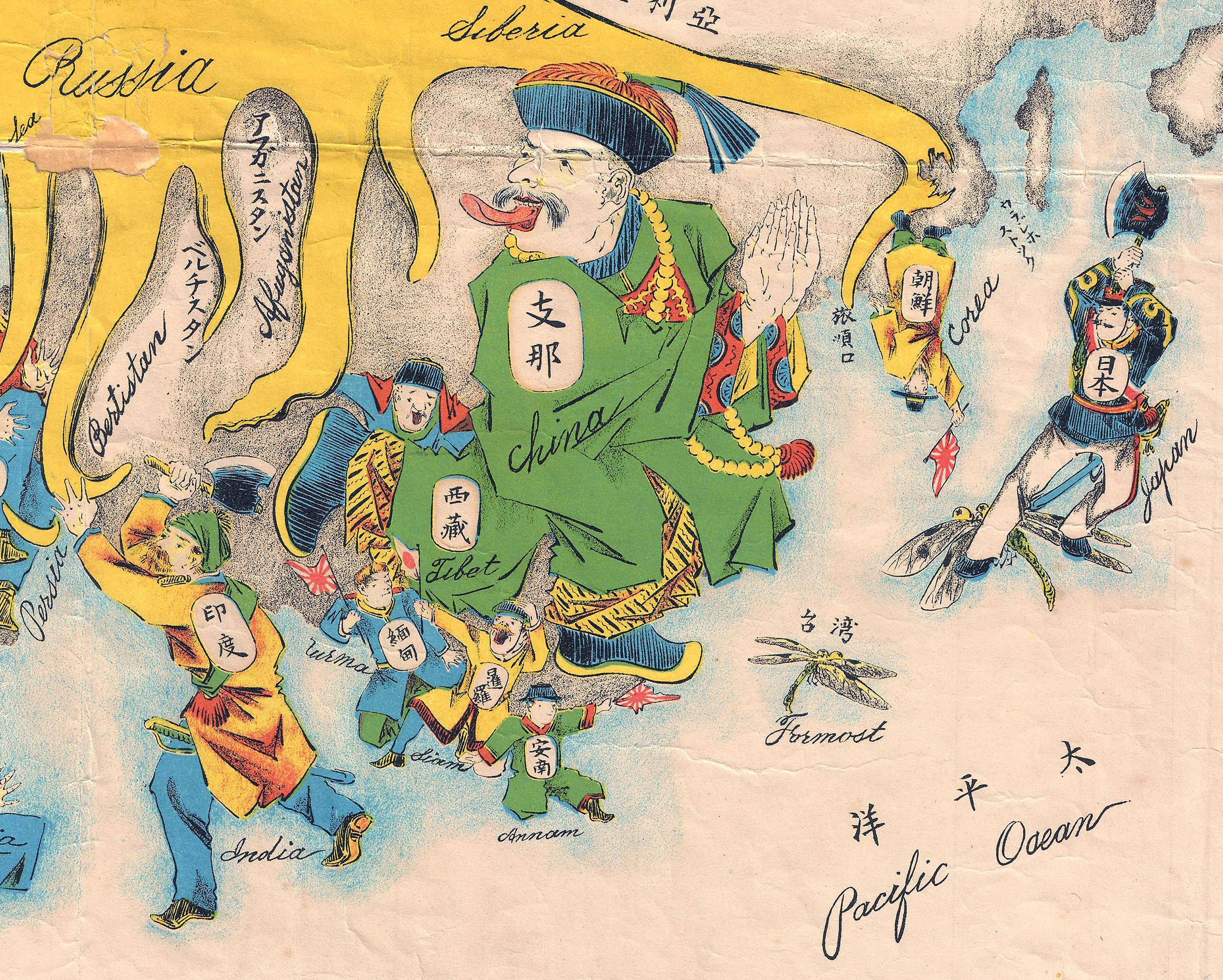

Kevin Brown: So, a recent unknown unknown that we discovered is a map I have in front of me right now and I’ll just describe it for your audience. It’s a Japanese map. A lot of the text is in Japanese, but its actual coverage extends all the way from Japan to England. The map is dominated by a giant tree which fills the entire center of the map. It’s weeping. It has a big nose, it’s kind of looking towards Japan, and its root system extends all throughout Europe and Central Asia and Southeast Asia. Now, this giant tree is representative of Russia. This map was issued in 1904, which was [in the middle of] the Russo-Japanese War in which Russia kind of got their asses kicked. I can’t say that, can I?

A seriocomic map from Japan titled 滑稽諷刺歐亞形勢圖 [Humor Reproach Candition Map of Europa and Asia], 1904. 15 by 21 inches. Courtesy of Geographicus Rare Antique Maps.

Kevin Brown: Ok, so, Russia kind of got their asses kicked by Japan and the map, it is in . . . it’s mostly in Japanese but it’s also in English. There’s an English title which I will translate . . . I will read literally: “Humor Reproach Candition Map of Europa and Asia.” So, the English is not that good.

“Early on as a dealer I would not really focus on known knowns because you’re not going to make that much money. Known unknowns are better because if you have a lot of knowledge then you can say ‘Aha! I know what this is!’ at a little antiques shop in Wichita [for instance], buy it cheap, and mark it up.”

Benjamin Miller: I can’t really make sense of that.

Kevin Brown: And there’s also an English text blog which I will not attempt to read because it is, for all intents and purposes jibber—

Benjamin Miller: Gibberish.

Kevin Brown: But it . . . I mean, there are real words there, but they don’t . . . they don’t make sense.

Benjamin Miller: Ok.

Kevin Brown: There is a Japanese text block as well, which is much easier to read and it describes how all the world is celebrating for Japan’s great defeat of Russia who is intimidating all of Europe.

Benjamin Miller: Wow.

Kevin Brown: Which at the time one could arguably say it was.

Detail of 滑稽諷刺歐亞形勢圖 [Humor Reproach Candition Map of Europa and Asia], 1904. Courtesy of Geographicus Rare Antique Maps.

Kevin Brown: It’s a very political map. The fact that it’s in both English and Japanese suggests something very interesting and the fact that Japan is on one end and England is at the other. They’re wearing the same color coats. England is holding a Japanese flag and the message here is “we are partners, we . . . let’s join together to fight this common enemy who’s horrible and is dominating the world.” This kind of map emerged first in Europe, but the Japanese were very quick to embrace it and they issued several maps regarding the Russo-Japanese War, four that I’m aware of, and this map was previously unknown. This is the only known example anywhere; there are no references to it. It is . . . it is a perfect unknown unknown.

“I knew it was a seriocomic map. Japan wields an axe and is chopping off Russia’s legs and I recognized that as relating to the Siege of Port Arthur and other events associated with the Russo-Japanese War. Because I hadn’t seen it, I knew that it must be exceedingly rare. So, all of these things together enabled me to assess this map even though I had never actually seen the map itself.”

Benjamin Miller: Did you know what it was as soon as he saw it?

Kevin Brown: I knew what it had to be in the sense that I knew it was a Japanese map. I knew it was in the model that was known as a seriocomic map (where cartoonish figures represent different countries). I know from the date what it was covering and from the iconography on the map. For example, Japan wields an axe and is chopping off Russia’s legs and I recognize that as relating to, say, the Siege of Port Arthur and other events associated with the Russo-Japanese War. I also know [that] because I haven’t seen it that it must be exceedingly rare, so . . . or unheard of, which, in fact, it is. So, all of these things together enable me to make a decision on this map about my own desire to represent it and place it within the context of other similar maps even though I had never actually seen the map itself before.

Benjamin Miller: Fabulous. Is there anything else you’d like our listeners to know about you and about your world of maps?

Kevin Brown: Only that, you know, we’re Geographicus Rare Antique Maps, www.geographicus.com, we exhibit at shows all over the world, and if you’re interested in buying an antique map or just learning more about antique maps I hope you’ll check out our site or sign up for our mailing list.

Benjamin Miller: Alright, well, thanks so much, Kevin.

Kevin Brown: Thank you.

Benjamin Miller: That’s a wrap on today’s episode. I hope you enjoyed it and maybe learned a thing or two. Don’t forget to rate us on iTunes and send your feedback to me at podcast@themagazineantiques.com or on Instagram @objectiveinterest. And one more reminder to post your own curious object on Instagram with the #mycuriousobject hashtag, tagging @antiquesmag. Today’s episode was produced and edited by Sammy Dalati. Our music is by Trap Rabbit. I’m Ben Miller, and I’ll see you next time.

Kevin Brown representing Geographicus at the Miami Map Fair. Courtesy of History Miami.

Kevin Brown is the founder and owner of Geographicus Rare Antique Maps, specialist dealers in antiquarian cartography from the fifteenth through the early twentieth centuries. The company is based out of Brown’s home in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, New York, but is most active at shows all over the world and online through their web portal, www.geographicus.com. Kevin is the author of A Journey Back in Time through Maps (White Star, 2017) and an upcoming work on historical city plans. In addition to his work with antique maps, Kevin is also the co-founder and co-owner, along with partner Yuan Ji, of Erstwhile Mezcal, a Brooklyn based importer of artisanally-produced agave spirits from Oaxaca, Mexico. When not searching the world for rare maps, or chopping agave stalks in Oaxaca, Kevin enjoys studying ninjutsu, sipping cocktails, restoring his historic brownstone, and taking walks with his dog, Shumi.

For more Curious Objects with Benjamin Miller, listen to us on iTunes or SoundCloud. If you have any questions or comments, send us an email at podcast@themagazineantiques.com.