Benjamin Miller caught up with Hirschl & Adler Galleries president Stuart Feld in this second episode of The Magazine ANTIQUES’ podcast Curious Objects. In question was a Boston-made neoclassical linen press, which served as entry point into a discussion about provenance (the linen press has been owned by Hirschl & Adler at three different times) and the more general ins-and-outs of antiquing. Feld, who’s spent more than fifty years at Hirschl & Adler, has been a nonpareil witness to changes in the business , and has plenty to say about the effects of the Internet, the joys of his own job, and the potential pitfalls of buying at auction.

Benjamin Miller, Host of Curious Objects & the stories behind them

Benjamin Miller is a director of research at the silver firm S. J. Shrubsole, and one of the rising young stars of the New York art and antiques scene. An urbane compère in the mold of Dick Cavett, Ben combines the friendly graciousness of his native Tennessee with the polish of his Yale education.

Stuart Feld. Courtesy Hirschl & Adler

Stuart Feld graduated from Princeton University in 1957 with an A. B. in the Department of Art and Archaeology. He completed his graduate studies at the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University in 1961. From 1962 to 1967 he worked in the Department of American Paintings and Sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, during which time he co-authored American Paintings: A Catalogue of the Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1967, Stuart left his post as Associate Curator in Charge of the Department and joined Hirschl & Adler Galleries as a partner, becoming its sole proprietor in 1982. Stuart has authored many articles and catalogues in the field of American Art—both fine and decorative arts—and is a frequent lecturer around the country. He is currently working with Kathleen Burnside on the definitive catalogue raisonné of the work of the American impressionist painter Childe Hassam.

Stuart Feld: The form, the monumental scale, the extraordinary selection of woods—all of these come together in a piece that thus deserves the name of “masterpiece.”

Benjamin Miller: Curious Objects is sponsored by Reynolda House Museum of American Art, one of the nation’s most highly regarded collections of American art, on view in the unique domestic setting of the 1917 R. J. Reynolds mansion. Browse the art and decorative arts collection at reynoldahouse.org—that’s R-E-Y-N-O-L-D-A house dot org—and visit in person in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Welcome to another episode of Curious Objects & The Stories Behind Them, brought to you by The Magazine ANTIQUES. I’m your host, Ben Miller, and for today’s episode I went to the legendary New York firm Hirschl & Adler, where I spoke with their president, Stuart Feld. Stuart is well known in the antiques world as a connoisseur across many different specialties, and in our conversation I tried to get a sense for what it means to be an expert in, well, everything. So, while the focus is a remarkable early Boston linen press, we touch on some wide-ranging ideas that I think will be interesting for collectors from all backgrounds. I spoke with Stuart Feld in his office, so don’t be alarmed if you hear some papers rustling and other antique dealer kinds of noises. The first half of our conversation focuses on the linen press itself, and in the second half we dive into the antiques business and the research process and Stuart Feld’s own fascinating biography and some tips and tricks for collectors of all kinds. I’m eager to hear your feedback on this episode and on the podcast more generally, so, if you have suggestions for future interviews or anything else to tell me, please send an email to podcast@themagazineantiques.com. I do read every email and I try to respond to as many as I can. So, thank you so much for helping out. If you’re enjoying the podcast, please leave a rating on iTunes or whatever podcast app you’re using to help other podcast listeners find us. Without further ado, Stuart Feld.

Well, with that, let’s jump into talking about this linen press. Tell me a little bit about this object. We’re sitting in front of it right now, and it’s, I have to say, a very imposing, almost regal sort of a piece. Can you give a physical description for our listeners?

Stuart Feld: The linen press is something of a boomerang, in that we have had this piece three different times. We’ve owned it three different times going back to 1984. We initially sold it to Wendell Cherry, who was a very major collector in his time. He unfortunately died early. We reacquired the piece; we then sold it to another legendary collector whose name was Jack Warner—collecting corporate collections for Gulf states paper—and we have since bought it back from that collection. And here it sits and we’ve not had it for very long and we have, as I recall, I think we’ve shown it once in that period of time. At any rate, it is a linen press. It was used to store perhaps household linens, perhaps actually clothes. Clothes were oftentimes folded and put into a linen press rather than hung up in a closet as we do today. The piece is made entirely of mahogany and parts of it are quite simple but it has a very, very elaborate entablature with typical Boston carvings of anthemia, lotus leaves, and scrolls. All of these elements appear and reappear on Boston neoclassical furniture. Unlike much furniture made in New York, which often has lots of ormolu and other decoration, much of Boston furniture simply relies upon a beautiful selection of woods, a very careful selection of woods, for its principal aesthetic motif. Here you can see in the doors, matched pairs of mahogany veneers, and the same thing up above and down below. And this piece represents one of a couple of most beautiful, most important, best of Boston neoclassical pieces of case furniture. The doors in the top open to a series of slides and then there are two small drawers over two long drawers in the base below.

Benjamin Miller: And the corners here are defined by columns.

Stuart Feld: And there are columns both above and below, really columnettes. And the piece retains its original turned mahogany knobs. And I mention those because that is very, very typical of a Boston aesthetic of this period. For years, pieces that came down to us with their original wooden knobs had the knobs taken off and shiny brass knobs were put on to tart up the piece a bit. This piece retains its original knobs, and to the extent that we’ve ever acquired a piece that had its knobs removed, we tend to find a set of old knobs or have a set made in order to restore it to its original appearance. Happily, that wasn’t necessary in this piece.

“The form, the monumental scale, the extraordinary selection of woods—all of these come together in a piece that thus deserves the name of masterpiece.”

Benjamin Miller: And are the knobs made from the same mahogany as the rest of the piece?

Stuart Feld: They are, yes.

Benjamin Miller: That mahogany would have come from the Caribbean, or . . . ?

Stuart Feld: Well, you know, there’s Cuban mahogany, there’s Honduran mahogany . . . I must say that I’m not a great expert on determining where the woods, or the specific pieces, come from, but let’s say that they all came from the greater Caribbean area, number one. And number two: it is virtually impossible to get that kind of mahogany today. First of all, to the extent that the trees might still exist in these places they are not allowed to be exported, and we are certainly not allowed to import them. And many pieces of Boston furniture are made of rosewood, Brazilian rosewood, and that is definitely not allowed to be imported today.

Benjamin Miller: So, give me a circa date here.

Stuart Feld: It was made just around 1825. And therein lies a difficulty in making a firm attribution because the two great cabinetmaking firms in Boston, in the neoclassical period, were Isaac Vose & Son, and Isaac Vose died in 1823 and the firm stayed in business until 1825. And the other firm was Emmons & Archibald. And again, I think Emmons died in 1825, early in 1825. Now based upon the writing in the drawers and elsewhere, Robert Mussey, who is a very serious scholar on the work of Thomas Seymour and Isaac Vose, believes that the writing is that of Thomas Seymour. And Seymour, after closing his own shop in 1817, went a year or two later to work for the firm of Isaac Vose. What happened to him after the closure of that firm is not known. So, who made this piece? Well, it could have been one of the last pieces that came out of the Vose shop before it closed in 1825. Or, it could have been made by Archibald after the death of Emmons in 1825. But we don’t know so much about what Archibald was making when he was working alone.

Benjamin Miller: How many comparable pieces would you say there are in the world, linen presses from Boston in the 1820s? Is this a singularity or are there a handful?

Stuart Feld: There are certainly other linen presses and armoires, but I think it’s generally acknowledged that this is one of the two finest ones. The other one is in a New York private collection. It was made for David Sears who lived in a very grand house designed by Alexander Parris on Beacon Street on Beacon Hill. And that is in the other Boston taste and is very richly ornamented with many pieces of many ormolu mounts.

Benjamin Miller: Oh, right. So, tell me a little bit about the aesthetic origins of this piece. What are the major stylistic influences?

Stuart Feld: Well, the piece—whereas the Sears piece that I just mentioned—the form of the piece is very much in the manner of English Regency pieces. The mounts are not only in the French taste, but the mounts on that piece are all imported French empire mounts. Here, this represents another aspect of Boston taste and it relies to a certain extent, very creatively, on a few design books published in London, one being John Taylor’s The Upholsterer’s and Cabinetmaker’s Pocket Assistant of 1825. And I think that plate two shows a general composition; it’s closely related to it. And then, if one refers to George Smith’s Cabinet-maker and Upholsterer’s Guide of 1826, there are certainly plates there that relate to certain details in this cabinet. It’s interesting that those two publications are of 1825 and 1826, which is just at this critical moment in Boston when one of the two great cabinet shops simply closes in 1825, the Vose shop, and the Emmons & Archibald shop is disrupted by Emmon’s death early in 1825. And, as I said, the mystery remaining of just exactly what Archibald was making on his own . . .

Benjamin Miller: Would your instincts be that those plates might have actually been seen by the maker of this cabinet?

Stuart Feld: Oh yes. Oh yes. It’s well known that a number of different design books were available to not only Boston cabinet makers but cabinet makers all over, the sophisticated cabinet shops all over the East Coast: Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and so on.

Neo-Classical Linen Press by Thomas Seymour (1771–1848), c. 1825. Courtesy Hirschl & Adler

Benjamin Miller: So, what separates this piece from other pieces made in Boston at the time? What are the unique characters?

Stuart Feld: The combination of the form, the monumental scale, the extraordinary selection of woods, all of these add up to what we call quality. And they all come together in a piece that thus deserves the name of masterpiece.

Benjamin Miller: It’s not known specifically for whom the piece is made, but what do we know about the provenance?

Stuart Feld: We don’t know anything about provenance, but what interests me about provenance in a general way is that the furniture that we deal in, and that I am specifically interested in, was made roughly between 1810 and 1840 and is thus several generations younger than Chippendale and Queen Anne furniture. And although I have bought a great many major pieces of neoclassical furniture over the years, very few of them have come down with a meaningful, accurate, verifiable provenance. And when I go to this auction or that and see the Jeremiah-so-and-so-family-Queen-Anne lowboy, or the whatever, I am in disbelief that these provenances are necessarily accurate. It doesn’t make sense that pieces that are fifty–seventy-five years younger rarely come down with a provenance, and these eighteenth-century pieces frequently do. I suspect that a lot of them are creatively arrived at.

Benjamin Miller: There may be some wishful thinking involved there.

Stuart Feld: I don’t think there’s any question about that.

Benjamin Miller: Interesting. Now, whoever it is made for, why would the customer have chosen to buy an American piece of furniture instead of an imported English piece.

Stuart Feld: Well, that’s a good question, and we’re learning more and more about the quantity of furniture being imported into the United States during this period, and to a certain extent pieces being made here were being made in exact, or nearly exact, replication of some of the imported pieces. On the other hand, there is, starting in the seventeenth century, there was great furniture being made variously in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, and beyond to a certain extent. There was a serious patronage for the craftsmen producing the furniture, the silver, and so forth. Many of the great houses of the period we know were furnished with domestically produced furniture. That doesn’t mean that in the same households there might not have been the occasional—or perhaps more than occasional—piece of English or French furniture.

Benjamin Miller: And would American furniture have been less expensive? Would it have been more expensive? What would the differences be?

Stuart Feld: I don’t know the answer to that, but let’s say that pieces of the sort that we are interested in would not have been inexpensive pieces of furniture in their day because they represent the very best of what was made. And, like . . . Albert Sack years ago wrote a book called, The Good, Better, Best of American Furniture. It’s largely furniture made before about 1810. He very rarely gets into the real high American neoclassical period. But, if such a book were written (and it’s been suggested that I do so, but I don’t have that in mind) on the, “good, better, best” of American neoclassical furniture, a piece like the linen press that we’ve been talking about would certainly rank as a masterpiece. One of the reasons I don’t want to do it is that, how do you tell some private lady that her card table is going to be a “good”—

Benjamin Miller: Merely good.

Stuart Feld: —when it came down from grandmama who thought it was the very best thing that had ever been made. So there’s no point in our getting involved in anything like that, but we are interested in the pieces that, in an expansion of the Sack aesthetic, would have been described by him as masterpiece.

Benjamin Miller: Let’s take a quick break. As they say in radio, “stay tuned.” Next up, I’ll ask Stuart Feld about his own personal story and for some advice about collecting.

Curious Objects is sponsored by Reynolda House Museum of American Art, celebrating its fiftieth anniversary with a new publication, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories, that takes readers behind the scenes of one of the nation’s most prestigious collections. On the Albert Bierstadt masterpiece Sierra Nevada, museum founding president Barbara Babcock Millhouse remembers traveling to see Bierstadt’s views for herself. Quote: “It was as though I was sitting in a theater with an intense drama enacted in front of me. I knew at once that Bierstadt expressed in his paintings exactly what I felt.” So escape to Winston-Salem, North Carolina, to experience the unique views of Reynolda House Museum of American Art. American masterpieces surrounded by century-old decorative arts in an American country home. Reynolda House Museum of American Art in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Reynoldahouse.org.

Welcome back. Thanks again for listening. Don’t forget to leave us a rating and subscribe so you don’t miss any future episodes. And, again, if you have any comments or suggestions, send an email to podcast@themagazineantiques.com. Alright, let’s get back to Stuart Feld!

Benjamin Miller: Now, I want to ask a few questions about you and your background, but is there anything else that you’d really like listeners to know about this particular piece?

Stuart Feld: I think basically we’ve covered it. It shows, you know, many of the key elements in Boston furniture this period. On the other hand, the aesthetic is firmly grounded in English Regency design.

Benjamin Miller: Now, you are, and we are, sitting right now at Hirschl & Adler, the legendary gallery in midtown Manhattan. And I have to say, as I walked in—this is my first time in your gallery—it’s astonishing the range of objects that you deal with. I mean, there are paintings, there is furniture, there is sculptural works, you name it. You’ve published books on all of these different subjects, on early American furniture, on early American painting, also on American Impressionism, on an incredible variety of subjects. Now, I have to ask . . . it seems hard enough to me to be an expert in one thing, how do you become an expert in half a dozen, a dozen different, completely different subject areas?

Stuart Feld: Well, you know that is something that when I was much younger puzzled me as well. And although in graduate school I had already, I think, become something of an expert in the field of American paintings, when I was leaving graduate school for one year to take a fellowship at the Met I was placed in the department of European Decorative Arts, and I was very puzzled about that. But my advisor at Harvard, where I was doing my graduate work, said that once you have become an expert in one field it is much easier to transfer that level of expertise to other fields as well. Well, as a kid of twenty-six or so I didn’t understand that, but I genuinely believe today that that is the case and can be the case. For example, I did start looking at American neoclassical furniture while I was in graduate school, and I started out knowing nothing. But I looked, and looked, and looked. There wasn’t much to see in museums, but I did see things at the dealers’. I did see things occasionally in books, and I did learn something about them. I then went on and wondered what the American silver was that was the parallel to the great furniture by Duncan Phyfe and Lannuier and others. And I was warned by the silver dealers of the moment with a quote that I’ve never forgotten: “Don’t ever buy a piece of silver, American Silver, made after 1800. It’s all junk.” Well, I have long since learned that that is not the case. And there was a question really of learning by looking, handling, and so on. And, of course, I have found that the most extraordinary silver was made in Philadelphia, in particular, but also there was wonderful silver made in Boston and New York as well, and occasionally elsewhere. So, I do think that one can learn either with a mentor or on one’s own about lots of other things as well. It’s been very beneficial to the business for us cumulatively to have that kind of expertise here. We never handle anything, by policy, where we don’t feel we have definitive expertise, so that we can transfer something to a new owner, whether it be an institution or a private person, without ultimate scholarship.

Benjamin Miller: I’m curious about this point because there’s another aspect to having expertise in a wide range of fields, which is, there are also auctions in different fields, and there are dealers in different fields, and there are collectors in different fields. And to be buying and selling objects across all these different disciplines, you have to have your finger on the pulse of so many different facets of the antique world. How do you keep up with all of that?

Stuart Feld: Well, it’s a very time-consuming thing, but I love what I do. I absolutely look forward to going to work every day. As of October 1, I will have been at the gallery, as a partner and for a long time as sole owner, for 50 years. And I have a way of kind of keeping in touch with the marketplace in the various areas that we’re interested in. And we have a staff of twenty, and if an object needs to be looked at either one of us will go do it or we have people we trust in various locations—cities across the country, even if something comes up in London or Paris—we have people who can look at things for us. If we think it’s advisable for us to go ourselves, one of us will do it.

Benjamin Miller: Now, you started your career in the academic and museum world. You picked up a couple of degrees. How did you go from there to the world of private dealing?

Stuart Feld: Well, I mentioned earlier that I had taken a fellowship at the Met and I started in the department of what was then called the department of Post-Renaissance Western European Decorative Arts. After being in that department for four months I was transferred to the American Wing, and during my tenure there in the late winter and spring of 1962 I was offered a job to stay on as a curator in the American Wing, which I declined because I had in mind going back to Cambridge to complete my graduate work. Then, later in that semester, so to speak, I was offered a job to write the first-ever catalogue of the American paintings collection at the Met, and the first volume of that was published in 1965. In 1967, Tom Hoving became director of the Met and I did not want to work for him. And I left with the idea that I had been asked to write the Pelican history of American Art, and I was going to spend the next year and a half doing that, probably working in a carrel in the library. And then I started being offered jobs by various galleries which I hadn’t really thought about. I was offered a very interesting job at Wildenstein. I was offered a partnership at Kennedy Galleries, but the partnership offer at Hirschl & Adler seemed the most interesting to me and I accepted that and began work here on October 1, 1967.

Benjamin Miller: So we’re just two months shy now of an anniversary.

Stuart Feld: Of fifty years.

Benjamin Miller: Incredible. And what was that transition like—going from a world infused with research with academics, with academic thinking, to a world of wheeling and dealing?

Stuart Feld: Well, you know, I couldn’t divorce myself from my heritage and I had completely reorganized the archival systems in the American paintings department at the Met. And when I arrived at H&A I found that the place was not very well organized in terms of library, archives, and so on. And I completely changed that, reorganized it, adopted a format that I had created at the Met for our research and for our systems. And so, in a funny way, I have continued to do things exactly the way I was doing them there. Except here we actively buy all the time and museums buy occasionally. And we actively sell all of the time. And so, in a funny way, it’s a different kind of work, but, in another way, it’s the same.

Benjamin Miller: So you still . . . clearly are still applying serious scholarship to the pieces that you’re buying and selling.

Stuart Feld: Virtually every work of art that we offer for sale has been thoroughly researched and is documented to the largest extent that it can be documented. And all of that information goes along with each piece as it is sold, and is actually recorded on the bill of sale.

Benjamin Miller: Is there any particular kind of object that you enthusiastically collect for yourself?

Stuart Feld: The answer to that has to be, yes. I started buying American neoclassical furniture in my second year of graduate school and I’ve never stopped. And I was encouraged to add American neoclassical decorative arts to the kind of material that Hirschl & Adler offered for sale after my wife and I had filled a rather large apartment. And I guess I was too much of a junkie to stop, and so I gradually got into this business as well. And our daughter Elizabeth has been here for seventeen years or so, and is very much interested in the decorative arts and spends a considerable amount of her time working in this area as well.

Benjamin Miller: What was Hirschl & Adler handling before you joined?

Stuart Feld: The firm was handling American and European paintings and some works on paper and the occasional piece of sculpture. No decorative arts at all. And the focus of the firm was much more on European art than on American art, and one of the reasons that they wanted me to join the firm was to enhance its representation of American art. And I guess I’ve done that because we now deal in all aspects of American art from the beginning up until today.

Interior of Hirschl & Adler. Courtesy Hirschl & Adler.

Benjamin Miller: I want to ask a couple of questions about the business landscape. Everybody in the antiques world has a different idea of what’s going right, what’s going wrong, what’s changing for the better, what’s changing for the worst. Tell me about, specifically, a trend that seems to be happening with certain auction houses that are beginning to resemble retail outfits more and more in certain ways, conducting private sales, advertising directly to consumers, and relying less on dealers. How do you see that trend? Do you see that trend happening, and what do you think the effects of that are for dealers and for collectors?

Stuart Feld: I do see that happening, and it’s not something that happened at all years ago, or even, you know, ten years ago, less than now. It doesn’t adversely affect what we do in that we bring a very, very serious level of scholarship to the table and that is highly respected both by institutions and private collectors. I can’t tell you how often members of the staff of both of the major auction houses here in New York come to us for our opinion of something, and that can be in a variety of areas. And sometimes we see something that’s wrong and speak up. I’ve learned that sometimes they don’t particularly want to know, and I don’t speak just about the New York houses but in a general way. I remember once calling a friend of mine who owns an auction house out of town telling him that the picture on the cover of his current catalogue, current as of that day, had been here and is a fake.

Benjamin Miller: Oh, boy.

Stuart Feld: And his response was, “I wish you hadn’t told me.” And that’s an exact quote.

Benjamin Miller: Wow.

Stuart Feld: Because I guess that put him under a certain obligation to say something . . . which did not happen and the picture was sold anyway.

Benjamin Miller: Really?

Stuart Feld: So we are sometimes quite reluctant to express our opinion. And I think at an auction it’s certainly a “let the buyer beware” situation. Now as we sit here . . . we are sitting opposite one of those extraordinary dolphin sofas which were probably made here in New York around 1820. And this one is very much like one, for example, in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum. I’ve done something of a catalogue raisonné of the sofas and I think I’ve catalogued thirteen and a half of them. The half being of a full-size sofa that was at a later date cut down at one end to make it a recamier.

Benjamin Miller: Oh, right.

Benjamin Miller: Now, another one turned up at a recent sale in New York, and it took our daughter Liz and me to tell the auction house that the sofa had been substantially cut down. So you see we’re not concerned about the competition of an auction house or auction houses because we do bring to the table a serious level of expertise. And that is really, really important to a serious collector. It’s perhaps less important to the person who is simply, as they say, “decorating with antiques.” But it’s important that, before buying something, one should know how original the piece is, what the integrity is, and so forth.

“At an auction it’s certainly a let the buyer beware situation”

Benjamin Miller: Are your clients also generalists? Do they collect across disciplines, or do you have more specialist clients or both?

Stuart Feld: Well, because we show all of these things together, even people who hadn’t thought about buying—let’s say, furniture collectors who hadn’t thought about buying silver or a painting—are often tempted to do so here. Or people who are purely paintings collectors have come in and seen a piece of furniture or so that they couldn’t possibly resist and have acquired that. For example, Jack Warner, who, alas, died quite recently, was a very serious collector of American paintings. And I remember his seeing a pair of English patinated and gilt brass candlesticks with eagles at a Winter Antique Show and he bought those. And they were the first of literally dozens and dozens and dozens of pieces of American neoclassical furniture, silver, ceramics, glass, lighting that we sold him in ensuing years.

“I was warned by the silver dealers of the moment with a quote that I’ve never forgotten: ‘Don’t ever buy a piece of silver American silver made after 1800, it’s all junk.’ Well, I have long since learned that that is not the case.”

Benjamin Miller: So, much like with your interests, for a client, one specialty can lead to another and lead to another.

Stuart Feld: Yes.

Benjamin Miller: What kind of effect is the Internet having on the business and on your experience of dealing in these areas?

Stuart Feld: Well, we have, you know, our own website and we are constantly updating it and making it better. I must say, I think it serves us much more as an advertisement than it does as a specific selling tool. Having said that, we do sell something occasionally that way, and we also sell something occasionally via a site like 1stdibs. But I think they are much more valuable to us as a window onto what we do, and encourage people to make a visit, to call us and find out what we have in a certain field, and so on. At the other end of the spectrum, many auction houses that used to produce catalogues don’t do so so much anymore. But their sales are documented quite effectively online, and I do spend a certain amount of my time looking at specific sites. I don’t have the time just to surf the internet looking at random things, but if I have reason to think that a specific auction might be interesting, I will try to review the catalogue online.

Benjamin Miller: What do you think about the generational shift that a lot of people are perceiving in terms of declining interest in brown furniture, or in silver, in old decorative forms?

Stuart Feld: We have . . . Dealing in American neoclassical furniture, we have not seen the decline in interest in brown furniture. At the Winter Antique Show in 2017 we had . . . first of all, we had an extraordinary show, and, secondly, we sold almost every piece of furniture except a couple of card tables and a few chairs. But we sold almost everything else. We also sold some very major paintings. There seems to be a very serious interest in American neoclassical furniture and we’re finding it easier to sell than to buy at the level at which we’re interested in dealing, which is a top couple of percent of that market.

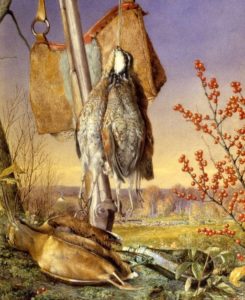

Hanging Trophies–Snipe and Woodcock in a Landscape by John W. Hill, 1867. Graphite, watercolor, and gouache; 20 by 16 inches. Courtesy Hirschl & Adler.

Benjamin Miller: Sure. Interesting. Let me ask a couple of questions that I ask all of my guests which are, first of all: What’s a piece of advice that you would give to a young collector just starting out in this field, maybe someone who’s listening now and intrigued by the idea of this linen press? What would you tell someone who was just thinking about dipping their feet into this world?

Stuart Feld: In all aspects of the material that we deal in, the pieces that are the best of their kind have held their value or have become more valuable. Whereas the more generic objects, whether they be decorative arts or fine arts, have really kind of lingered and there’s a lot less interest in them right now. As a . . . wearing my hat not as a dealer but as a private collector—and I was a private collector long before I became a dealer—I’ve always tried to seek out objects that I thought were really extraordinary, that were a little bit below the radar, because I could not economically compete with the person buying the great Philadelphia Chippendale highboy, or the Goddard-Townsend shell-carved kneehole desk, or whatever dressing table. And I settled years ago on American neoclassical furniture, which was not at that point of great popular interest. And that turned out to have been a very nice decision. One of the areas in the picture world that we have personally collected is the “American” (so-called) “pre-Raphaelites.” And we have collected extensively in that area, and, as a matter of fact, are significant lenders to a show of that material that will be at the National Gallery in Washington in the summer of 2018. My advice, in brief, would be, that you want to buy the absolute best that you can at a given moment.

Benjamin Miller: So our listeners ought to seek out areas that are under the radar, areas of collecting that are maybe out of vogue, but where they can afford to buy really excellent examples.

Stuart Feld: Unfortunately, having given this sage advice, I have to then say that there are fewer areas now that are under the radar than there were when I was getting started. But there are still the occasional beautiful thing that can be bought that is really great quality, that is not necessarily wildly expensive. But the best advice I would give is that if you yourself don’t know what you should be buying, then seek advice from somebody who does have a sense of where the market has been, where it’s going, and what the right things to be buying are at a given moment.

Benjamin Miller: Maybe someone at Hirschl & Adler.

Stuart Feld: That’s possible. But there are other people as well.

Benjamin Miller: What are some mistakes that you see even experienced collectors making that you would caution against?

Stuart Feld: It can best be described, I think, as “beating the system,” in that many collectors who really don’t have any experience and don’t know what they’re doing have gone out and tried to build a collection on their own where money is the chief decision-making factor in an acquisition. With the given that there are no bargains in an area that has been heavily collected over a long period of time, the thing you want to do is to buy the best thing you possibly can. And again, I repeat, because it’s really important: If you don’t know how to make the selection yourself you need to put yourself in the hands of somebody who can give you that advice. That advice does cost money, and some people giving that advice shouldn’t be giving any advice because they themselves don’t know. I mean . . .

Benjamin Miller: I won’t ask you to name names. Stuart Feld, thanks so much for being with us.

Stuart Feld: Thank you very much for asking me. It’s been a pleasure.

Benjamin Miller: Curious Objects is sponsored by Reynolda House Museum of American Art, one of the nation’s most highly regarded collections of American art, on view in the unique domestic setting of the 1917 R. J. Reynolds mansion. Browse the art and decorative arts collection at reynoldahouse.org. That’s R-E-Y-N-O-L-D-A house dot org, and visit in person in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

And thanks so much to all of you for listening. I really hope you enjoyed it. Curious Objects is a podcast from The Magazine ANTIQUES, today’s episode was edited by Sammy Dalati, and our music is by Trap Rabbit. Until next time, I’m your host, Ben Miller.

For more Curious Objects with Benjamin Miller, listen to us on iTunes or SoundCloud. If you have any questions or comments, send us an email at podcast@themagazineantiques.com