The Victoria and Albert Museum in London celebrates Magnificence of the Tsars with a sumptuous display of men’s ceremonial attire from the Russian imperial court on loan from the Moscow Kremlin Museums’ collections. What could be more fitting in the British capital that is currently nicknamed Londongrad or Moscow-on-the Thames for its several hundred thousand Russian émigrés and its dominant role in the market for Russian objects and art? However, in the wake of the recent economic crisis, during which the Russian stock exchange plunged by more than 65 percent of its value since May, and huge portions of the November Russian sales in London failed to sell, one wonders if this exhibition constitutes a belated finale to the boon for things Russian? Or does it hint that the Russian presence in the art world cannot be snuffed out by one mere blip on the radar-even a seemingly cataclysmic one?

According to Lesley Miller, senior curator of textiles and fashion at the Victoria and Albert, the show originated with a proposal for an exchange made to them by the Kremlin back in 2005, not long after the Russian market had exploded. Experts concur that the Russian industrialist Victor Vekselberg’s splashy purchase of Malcolm Forbes’s entire Fabergé collection in February 2004, two months before its scheduled auction at Sotheby’s in New York, marked this sea change. Renowned Fabergé expert Géza von Habsburg summarizes, “Prices rose slowly until the oligarchs made an appearance at the London auctions in November 2003; then, after the sale of the Forbes collection, they rose astronomically until the end of 2007.”

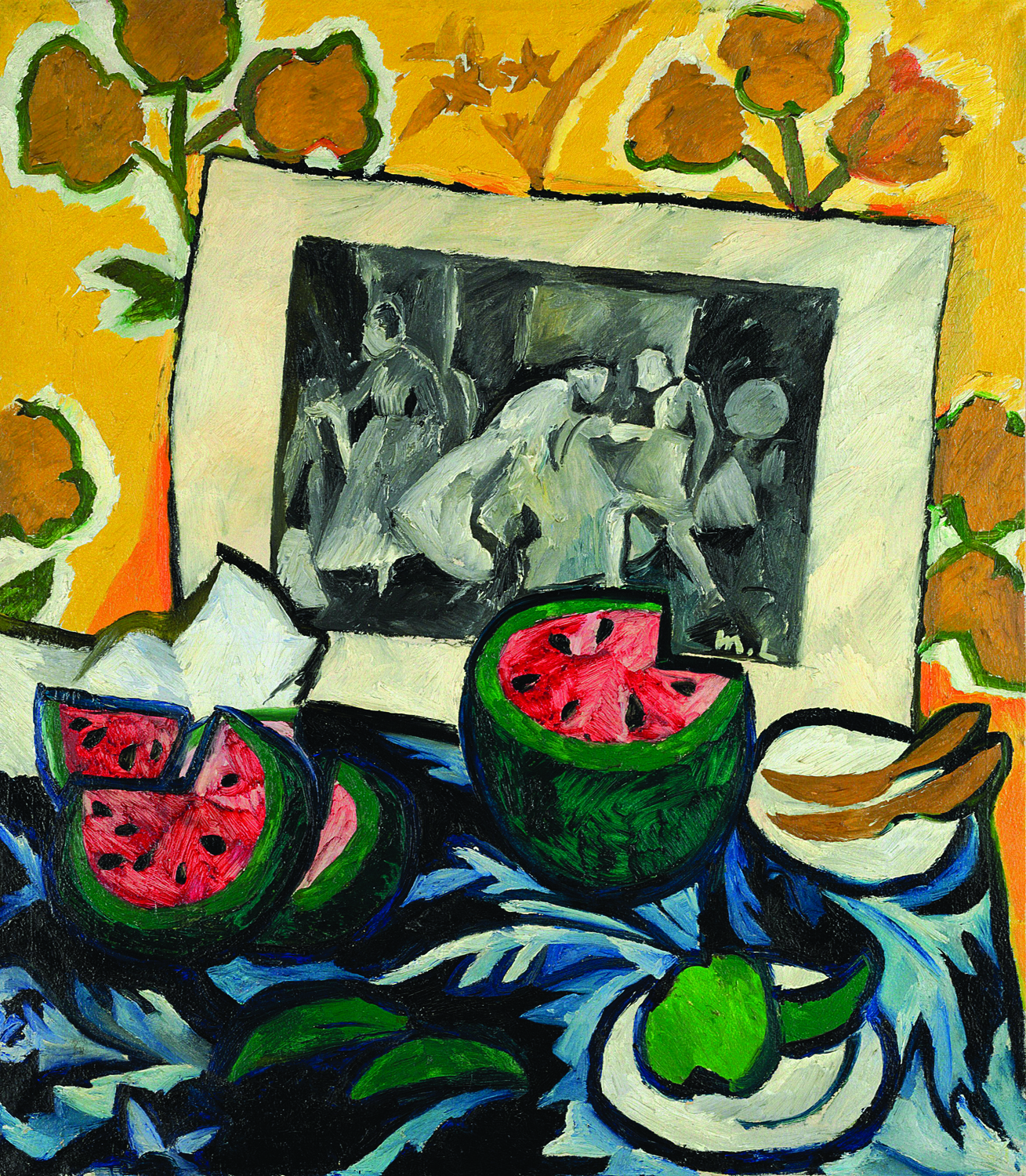

Although Christie’s in London sold the exquisite Rothschild Fabergé egg for $18.5 million (a world auction record for any work by Fabergé, any timepiece, and any Russian art object excluding paintings) in November 2007, the real action had shifted into new areas, especially paintings. That September Russian steel magnate Alisher Usmanov acquired the collection of the late cellist Mstislav Rostropovich and his wife Galina Vishnevskaya days before its scheduled auction at Sotheby’s in London for a sum described as “substantially higher” than the roughly $40 million that the sale had been estimated to bring at its highest. This notable assemblage of paintings, porcelains, and objects includes Faces of Russia by Boris Dmitrievich Grigoriev, a study of peasant faces painted at the time of the Revolution; and a selection of porcelain from the Orlov Service, commissioned by Catherine the Great for her lover Count Grigorii Grigorevich Orlov from the Imperial Porcelain Factory about 1765.

The Russian market has indisputably changed the landscape of the London art world, leading to new auction houses such as MacDougall’s, which specializes exclusively in Russian sales, and expanded sales calendars and staffs at Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Bonhams. However, experts unanimously agree that this is a global phenomenon-with heated activity in Stockholm, Copenhagen, Paris, New York, and beyond.

The Kremlin Museums’ reciprocal loan exhibitions with the Victoria and Albert stand as but one of many such projects that began even before this phenomenon. Von Habsburg, who has curated five blockbuster Fabergé exhibitions since 1986, points out that Russian-themed shows are not a new concept. Nevertheless, this past season the market has slowed considerably. Von Habsburg predicts, “We’ve hit the top. It’s a bit late to get on the bandwagon.”

Is Magnificence of the Tsars simply climbing on to the borscht train-an overcooked borscht at that? Miller, who, together with Susan North and Claire Brown at the Victoria and Albert, collaborated with Svetlana A. Amelekhina, curator of the imperial Dress Collections at the Moscow Kremlin Museums, feels confident that imperial Russia will always hold romantic appeal for Europeans as well as for the large community of Russian-speaking residents and visitors to London. Moreover, she explains that the team consciously chose to focus on exclusively male attire so that the scholarly aspects of the show might shine and to attract military history enthusiasts and others who might not usually attend either a Russian or a fashion exhibition.

The show features coronation outfits from every Russian emperor from Peter II in 1727 to Nicholas II in 1894, which the Armory chamber at the Kremlin, where each monarch was crowned, has miraculously retained. Together, these ceremonial garments trace the evolution of Russian imperial symbolism and taste. The boy emperor Peter II dressed in the height of Parisian fashion. By contrast, Paul I in 1797 wore a military uniform for his coronation, an innovation subsequently followed not just by his descendants but also by rulers all over Europe. When Alexander III was crowned in 1883 he, in turn, chose a jacket with a traditional Russian side-opening rather than a Western style cut, a choice that reflected the interest in returning to native motifs similarly evinced in music, art, and design.

The exhibition begins with an extensive look at Peter II’s wardrobe, including his dressing gown, stockings, and even his underwear, which survives because no one wanted to touch it after he died of smallpox at fourteen; and concludes with a five-meter-long ermine-trimmed coronation mantle identical to the one worn in 1896 by Nicholas II, the last of the Romanovs, and with a fancy-dress costume that incorporates seventeenth-century jewels of his ancestors. Accessories, accouterments, and a fascinating selection of coronation outfits worn by heralds, various orders of nobility, chamberlains, and coachmen round out this display, most of which has never been exhibited before either in Russia or abroad. Because of their rarified provenance, many of the items are well-documented as to their designers, fabrics, and manufacture, thus enlarging the fields of fashion and, indeed, social history.

Sarah Mansfield, head of Russian Pictures at Christie’s in London, suggests that the explosion of the Russian art market has created a new desire, as well as new opportunities, such as the Victoria and Albert’s exhibition, for non-Russians to expand their knowledge. She recalls that her own induction into Russian culture began as a literature student reading novels by Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Leo Tolstoy. She stresses that Les Fleurs of about 1912 by Natalia Goncharova, which sold for nearly $10.9 million in June 2008, holds the auction record for any work of art by a woman artist in the world, an achievement whose profundity she feels has not yet been sufficiently appreciated. Joanna Vickery, Sotheby’s senior director of Russian Paintings, Works of Art, and Icons, contends that, while “Russian music and literature have been so well loved even if people didn’t understand the culture that lay behind them, the corresponding paintings and art couldn’t travel before so they weren’t known in the same way.” When asked if the economic downturn will kill this interest, she insists, “The Russian art market, which ten years ago almost didn’t exist, except as an esoteric, minor thing, is now one of the most important and is the result of profound political and economic changes. Russian art is now firmly on the map.” Currently Paris’s Musée Maillol has on view through March 2 an outstanding selection of avant-garde Russian paintings-including works by suprematist, constructivist, and neo-figurative masters Kazimir Malevich, Liubov Popova, and Aleksandr Rodchenko-from the collection of Georgi Costakis, which are on loan from the Russian State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and the Greek State Museum of Contemporary Arts in Thessaloniki.

The newest shift in Russian collecting, an expansion out of indigenous objects and into Western culture, is exemplified by the massive response to the other half of the Victoria and Albert’s exchange with the Kremlin-Two Centuries of British Fashion, a display of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British dress from the London museum’s collections, held last fall at the Kremlin Armory Museum. A staggering twenty-four television channels and approximately 120 journalists turned up for the press viewing.

Vickery cautions, however, that although Russian collectors have branched out over the past couple of years, especially into impressionist and contemporary art, “it would be a mistake to think that they’re moving out of Russian art, and new collectors continue to appear.” Mansfield observes that these collectors are rapidly developing their eyes and their knowledge and asserts that the market is “much less faddish than people give it credit for.”

New York-based dealer Nicholas B. A. Nicholson concurs: “People joke about the Mafia taste of Russian collectors but that is not the taste of the new collectors. The first-group of post-Soviet collectors focused on their heritage, especially famous names such as Fabergé-a phenomenon that led to “many fakes and hyped up prices.” Now, he works with the children of these collectors, who perceive themselves as “European first and Russian second.” One such client has him on the trail of high quality art deco pieces by designers such as Jules Leleu; signed furniture from the 1940s to the 1960s; modern and contemporary Western art; and dramatic, “drop-dead gorgeous” ancien régime pieces that Nicholson describes as “what an aristocrat would have collected if the Revolution had never happened.” These collectors reprise the tradition of numerous pre-Revolutionary forerunners such as Sergei Shchukin, the visionary impressionist and post-impressionist enthusiast; and, far earlier and more extensively, by Catherine the Great. A magnificent silver soup-tureen from the empress’s Black Sea Fleet Service made in Saint Petersburg in 1766 by Zacharias Deichman in the shape of a fourteen-gun naval warship, which starred at Christie’s London sale this past season with an estimate of $640,000 to $960,000, failed to sell on November 24. Although it serves as a barometer of other fragile markets today, its exquisite craftsmanship stands as a reminder of the long and enduring history of Russian collecting and patronage.

Magnificence of the Tsars: Ceremonial Men’s Dress of the Russian Imperial Court, 1721-1917 from the collection of the Moscow Kremlin Museums · Victoria and Albert Museum, London · through March 29 · www.vam.ac.uk

L’avant-garde russe dans la collection Costakis · Musée Maillol, Paris · through March 2 · www.museemaillol.com