What’s old is new, what’s new is old. Eight of architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s idiosyncratic modern buildings have been added to the UNESCO World Heritage List, the international preservation organization announced on Sunday. They’re the first modern structures in the United States to receive the honor. “We consider it major recognition for all of Frank Lloyd Wright’s work,” says Joel Hoglund, communications director at the Chicago-based Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy, which worked with owners and operators of the eight properties, along with the National Park Service, to put together the proposal submitted to UNESCO.

Wright joins Europeans like Le Corbusier and Antoni Gaudí among the scant modernists on the UNESCO list, in what’s likely to prove a boon for ongoing preservation efforts at the three hundred–plus Wright buildings extant, as well as for other modern structures in the United States and abroad, which are under constant threat from developers, natural disasters, and decay. UNESCO listings “raise great awareness of the value [of] preservation of such types of sites,” says Mechtild Rössler, director of the UNESCO World Heritage Center. “It can also become an example of sharing conservation techniques with other site managers across the world and other examples of modern architecture already on the World Heritage List.” “We’re really hoping [the designations] make our job easier,” says Hoglund. “Hopefully a rising tide raises all ships.”

Compiled under the rubric “The 20th century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright,” the listing includes buildings that span almost the entire breadth of Wright’s career (omitted are examples of his earliest work, from the 1890s, immediately after he left the firm of Adler and Sullivan), beginning with Wright’s 1905–1908 Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois. Arguably the first house of worship to be built out of reinforced concrete, it’s the only surviving public building from Wright’s early “prairie” period, when he was perfecting the low-lying style of building that would become his signature. It reopened in 2017 after a two-year restoration by the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, which oversees Wright properties in and around Chicago.

The 1910 Frederick C. Robie House on the South Side is probably the best example of private prairie architecture, an outspreading mass of brick and limestone courses and leaded-glass ribbon windows patterned with abstract floral designs. Wright himself campaigned to save it from destruction twice during his lifetime—in 1941 and again in 1957—testifying to the personal pride he felt for this house.

Taliesin, which takes its name from a first century Celt bard, was built in three iterations between 1911 and 1925 in the hilly Driftless Area of southwestern Wisconsin. It formed the stage for some of the brightest chapters of Wright’s life, as well as its darkest: his paramour Mamah Bouton Borthwick was murdered there in 1914 by a deranged employee, along with six other people, and the complex was partially destroyed by fire.

The white, Mesoamerican-style Hollyhock House, the heart of an arts center in East Hollywood envisioned by oil heiress Aline Barnsdall, reopened in 2015 following a multimillion-dollar restoration. Wright worked Barnsdall’s favorite flower, the decorative Eurasian hollyhock, into the design in many ingenious ways, including in the house’s art glass windows.

The design of Wright’s best-known house, Fallingwater, in southwestern Pennsylvania, was seemingly produced in only a matter of hours, in a flight of pure inspiration. Cantilevered dramatically over one of the falls of Bear Run stream, this tour-de-force paved the way for Wright’s late-career resurgence, earning him a Time cover and an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

An excellent early example of Wright’s Usonian house concept—meant to be the basic unit of meaning in his Utopian vision for civic planning, Broadacre City—the Herbert and Katherine Jacobs House in Madison, Wisconsin is a demure structure presaging the modern ranch house. Designed and built in 1936–1937, it’s filled with Wright’s own custom wood furniture.

Taliesin West was built in Scottsdale, Arizona, as Wright’s winter home. A complex of fort-like rubble masonry buildings surmounted with wooden-beamed roofs and surrounded by pools and terraces, it was originally constructed with canvas sails on the roofs of the buildings, and was meant to evoke a ship. Conceived in 1937, the complex was continually modified until the architect’s death. Read more about Taliesin West here.

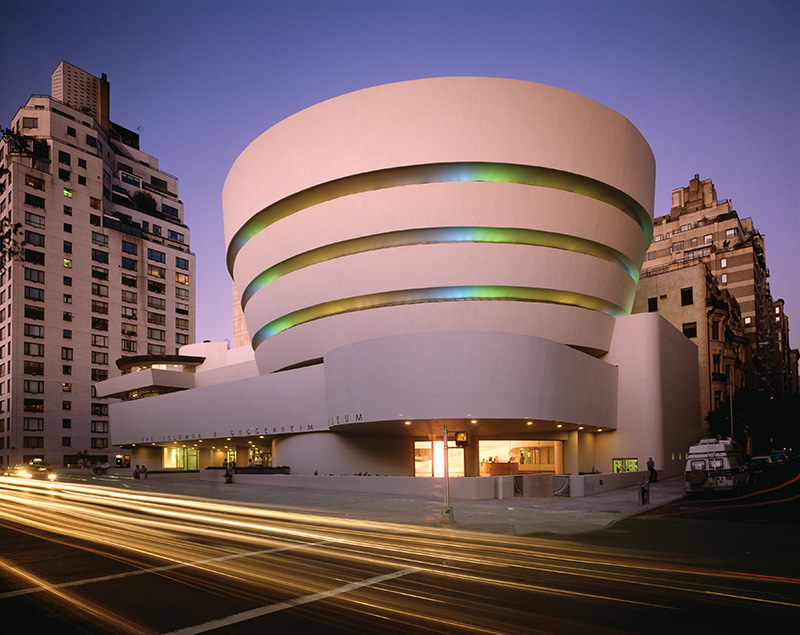

Wright didn’t care for the Big Apple, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum represents one of the architect’s few commissions in the city (and one of two surviving). Spurning the angular aesthetic of the grid, Wright designed a curvilinear building in billowing concrete brut that borrows its organicism from flora and fauna of the adjacent Central Park. In plan little more than a skylighted rotunda, the Guggenheim was built to house an abstract art collection, becoming itself one of the most recognizable abstract sculptures in the world. It opened its doors shortly after the architect’s death in 1959.