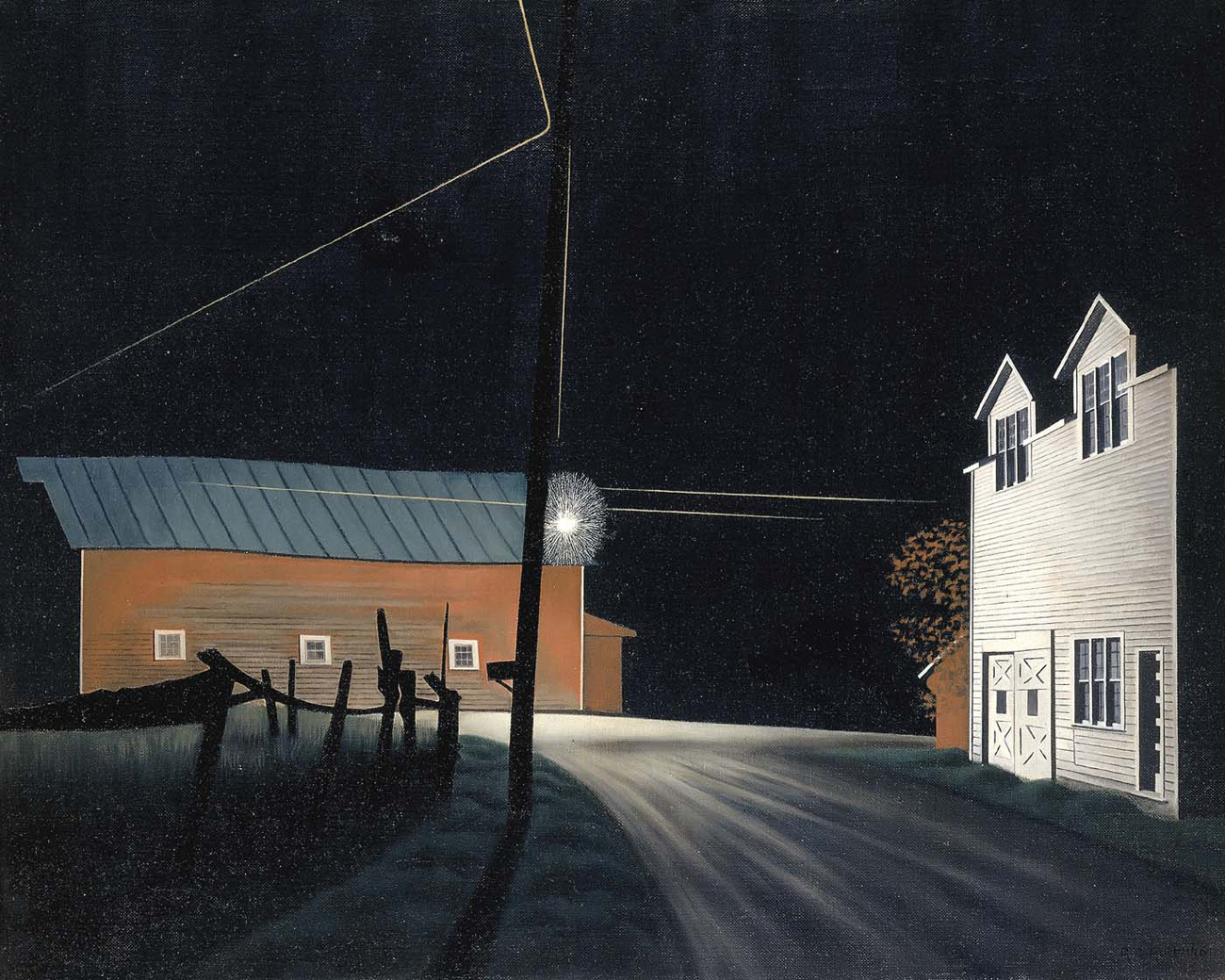

What does it mean for an artist to make a world? Consider the case of George Ault, and more especially of Black Night: Russell’s Corners (Fig. 1), a painting he made in 1943 in Woodstock, New York, where he moved in 1937 and lived until his death eleven years later. Showing old barns at a junction a few hundred yards from the town center, Ault portrayed a scene of meticulous order. The carefully ruled clapboards, double doors, and windows of the white barn, the neat roofs of the red ones, and the two telephone poles at the left combine to structure this crossroads lit so brilliantly by the single light hanging where the two roads meet.

Elements of disquiet are there, certainly: some windows of the red barn at left tilt strangely; the angled dead tree counters the straightness of the telephone poles; and the telephone wires disappear into the black night that gives the painting its title. But the sense of geometry wrested from blankness and emptiness remains. Ault “painted to make order out of chaos,” his friend John Ruggles recalled in 1949. “The words of A. E. Housman, ‘I, a stranger and afraid, in a world I never made,’ touched him acutely. Rebellious and disdainful of many things in life, he passed by means of his paintings from a world he did not make, into a world of his own.”1

‘I, a stranger and afraid, in a world I never made,’ touched him acutely. Rebellious and disdainful of many things in life, he passed by means of his paintings from a world he did not make, into a world of his own.”1

Ault’s wife, Louise, whom he had met in 1935 and married in 1941, knew well her husband’s sense of order. After becoming upset by some event in the world or in town, he could find peace, she wrote later, only “at his easel again, creating formal harmony—on his canvas bringing order out of chaos.”2 In 1942 Louise wrote of the Woodstock painter Henry Mattson’s “inward desire for order—the desire to bring order out of chaos—which is a primary impulse of the artist in expressing himself through his medium,” and she found the same quality in her husband’s art.3

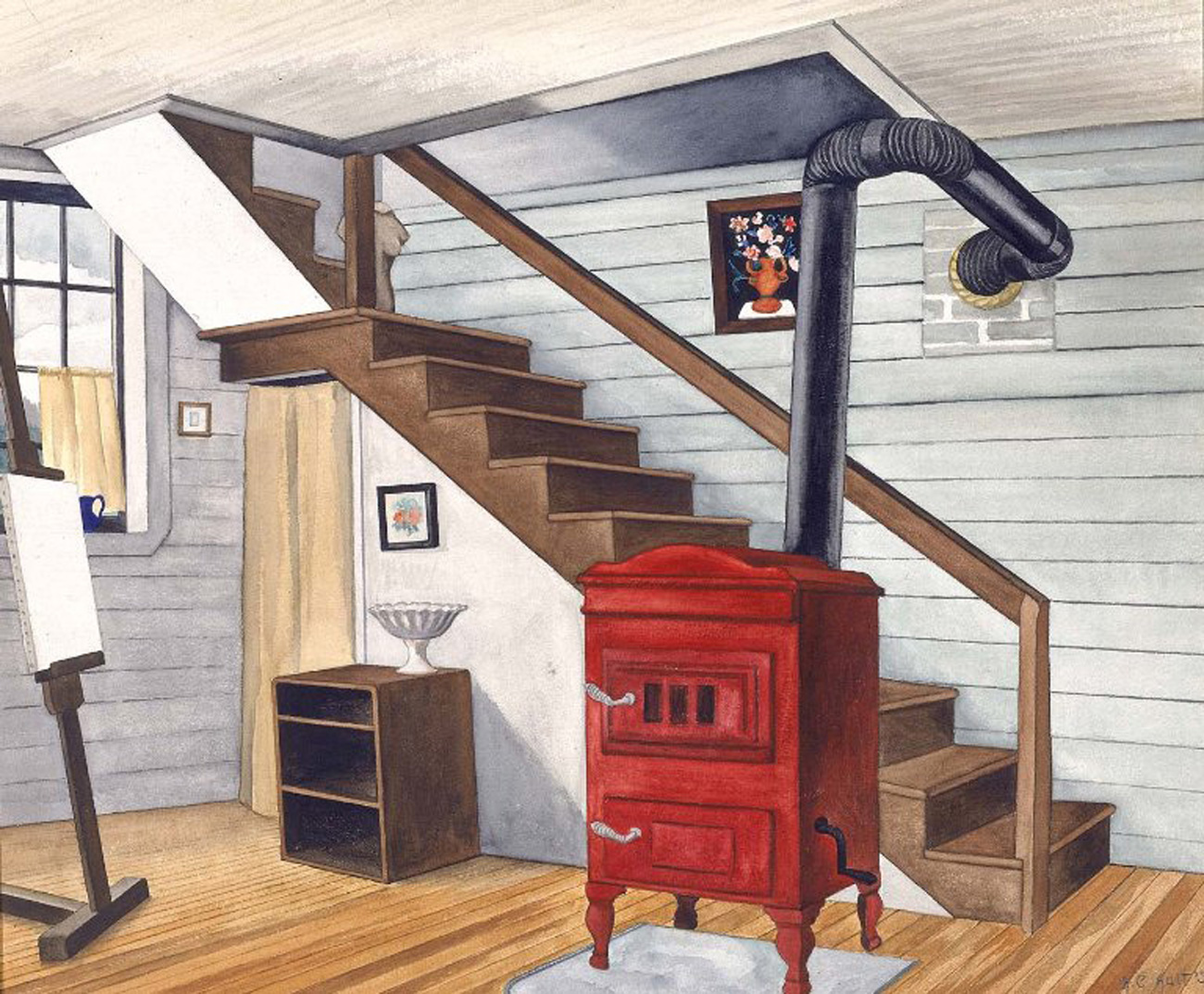

In Ault’s case, the order started where he and Louise lived, not far from Russell’s Corners. Their first house in Woodstock contained the studio he painted in a careful watercolor soon after they moved to the town (Fig. 2). Both studio and house needed to be perfectly clean before he could sit down at his easel. Ault would do the chores himself, Louise recalled, shining the small house each morning to its “permanent brilliance” before starting to paint. Outside, Ault “knelt with grass-shears and trimmed on either side of the path, close and neatly, cutting back the wildness to leave a park-like strip,” Louise wrote, and he “began a project of stone-laying, searching the acreage for flat rock, laying a terrace between back-porch steps and well, a stone path up to the mailbox, another on to where the underbrush ended and opened upon a little glade, and down to the outhouse.”4 Ault’s watercolor of the studio expressed this rage for order twice: once in the actual studio and again in the painting recording it.

What explains the order of Ault’s work? Since the 1920s he had composed his scenes geometrically, mixing modernist abstraction with recognizable places (often in Manhattan, where he lived for many years), but the Woodstock pictures seem especially precise, as if he felt much depended on his ability to align every angle, to make every slope of roof and roadside edge just so, as if each element carried the immense burden of staving off chaos. Maybe the reason was Woodstock itself. A remote location even with Byrdcliffe, its artists’ colony, the town required a hardy person to shape a life’s work there, and some of the Aults’ friends there, the sculptor Alfeo Faggi (1885–1966) and the painter Georgina Klitgaard (1893–1976), for example, attested to the fact.5 But to believe that Woodstock alone explains the order of his work is to shortchange the obsessiveness of Ault’s clarity.

Maybe the order arose from a deeply personal cause. Few other artists suffered so much personal misfortune as Ault. In 1915 his younger brother Harold killed himself in a suicide pact with his wife. In 1920 his mother died of anemia in a mental hospital. In 1929 his father died of cancer, the year the family’s savings were lost in the stock market crash. In 1930 and 1931 Ault’s two remaining brothers Donald and Charles killed themselves, one with gas, the other with strychnine.6 By the time he moved to Woodstock with Louise in 1937, Ault was a depressed, irritable alcoholic who had lost his gallery representation and alienated many of his artist friends and acquaintances. Perhaps his family’s suffering was the chaos he made order from in impeccably controlled pictures such as Black Night: Russell’s Corners.

Yet what if that order came about for more than personal reasons? Ault felt that an art based on individual experience was limited. He praised an article published in 1940 in Partisan Review that noted the “shallowness” of expression based on “private interests.”7 There had to be a sense of the wide world channeling through one’s work. Accordingly, what if an infinite black night, World War II, lurks as the universal abyss that Ault’s rural junction would stand up to and somehow, symbolically, try to control? If that worldwide chaos could stop—if the universal emptiness could be suspended, if only for a time, in a perfect structure of balance and compass—then one might achieve, in the devastating uncertainty of 1943, a measure of peace.

Keeping to himself in Woodstock, Ault was deeply affected by the war. The day after France fell in 1940, Louise saw him get up abruptly from the easel and go out the back door: “I saw him sitting on the porch steps, face buried in his hands; I found him sobbing.” She also remembered that “as Hitler’s armies spread out in victorious marches, he scanned the headlines of the New York Times, his hands trembling from the agitation they caused him, then put the newspaper aside for calm perusal in the evening and sat down at his easel to paint.” Having vacationed in France as a boy, back when the Aults lived in England from 1899 to 1910 when his father ran the family business there, Ault could not believe it: “Paris in the hands of Germans!”8 In 1944 he would make pictures recalling his boyhood experiences at Cap Gris-Nez on the Pas-de-Calais—the French beaches now sadly and sinisterly transformed—such as Memories of the Coast of France and The Cable Station.

Maybe even Ault’s painting of a junction in his small town, so remote and unrelated to international headlines, was a response to the world’s chaos. Ault painted Russell’s Corners five times, the subsequent versions coming in 1944 (his only daytime treatment of the scene), 1946 (twice, see Fig. 4), and 1948 (Fig. 6), but it is significant that he made his first picture of the subject in 1943, as if wartime were the impetus. What then if the steady hand were responding to the trembling hand, and in such a way that both the calm and the chaos, the clarity and the black night itself, were evoked in his brooding picture?

In 1938 Thornton Wilder (1897–1975) had described the cosmic place of another corners—the mythical town of Grover’s Corners, setting for his celebrated play Our Town, where Rebecca Gibbs tells her brother George about the address on a letter his friend Jane Crofut received: “Jane Crofut; the Crofut Farm; Grover’s Corners; Sutton County; New Hampshire; United States of America…. Continent of North America; Western Hemisphere; the Earth; the Solar System; the Universe; the Mind of God.”9 The only difference between Grover’s Corners and Russell’s Corners was Ault’s blacker night. The country crossroads made a small and delicate order, a fragile array of sharp forms, but the universe pressed down. The little buildings “shoulder the sky,” to cite a phrase of Housman’s that Ault loved.10 Impossible burdens afflicted the wartime imagination.

But would the message get out? “Only Walt Whitman and I cry straight from the heart,” Ault told Louise, but could the cry be heard?11 Consider Bright Light at Russell’s Corners (Fig. 4), Ault’s next nighttime version of the scene, painted in 1946, which positions us on the lower Glasco Turnpike, looking back to the intersection past the white barn.

Consider especially the geometry of telephone lines, which imply Ault’s views about communication. Appearing and disappearing in the night, the lines suggest voices framed against those black nights Ault loved to paint, where they stand out as cat scratches on the darkness.

Without great faith in the world, Ault painted pictures he thought would go into the void of space and time. When a Pittsburgh couple, Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Lawrence, wrote to him to express their admiration of Bright Light at Russell’s Corners (they had seen the painting at the Carnegie annual exhibition in 1947, purchased it, and later gave it to the National Collection of Fine Arts [now the Smithsonian American Art Museum]), Ault expressed his sincere thanks and, really, his surprise. “It is not often that an artist gets such heartfelt response from those who have acquired a work of his. It is usually just, ‘we like your picture very much’ or ‘it’s awfully nice,’ and that’s all one hears and the picture disappears into the void,” he wrote. “I’ve sold many pictures during the past twenty-five years and I haven’t the faintest idea of what has become of them, or most of them.”12

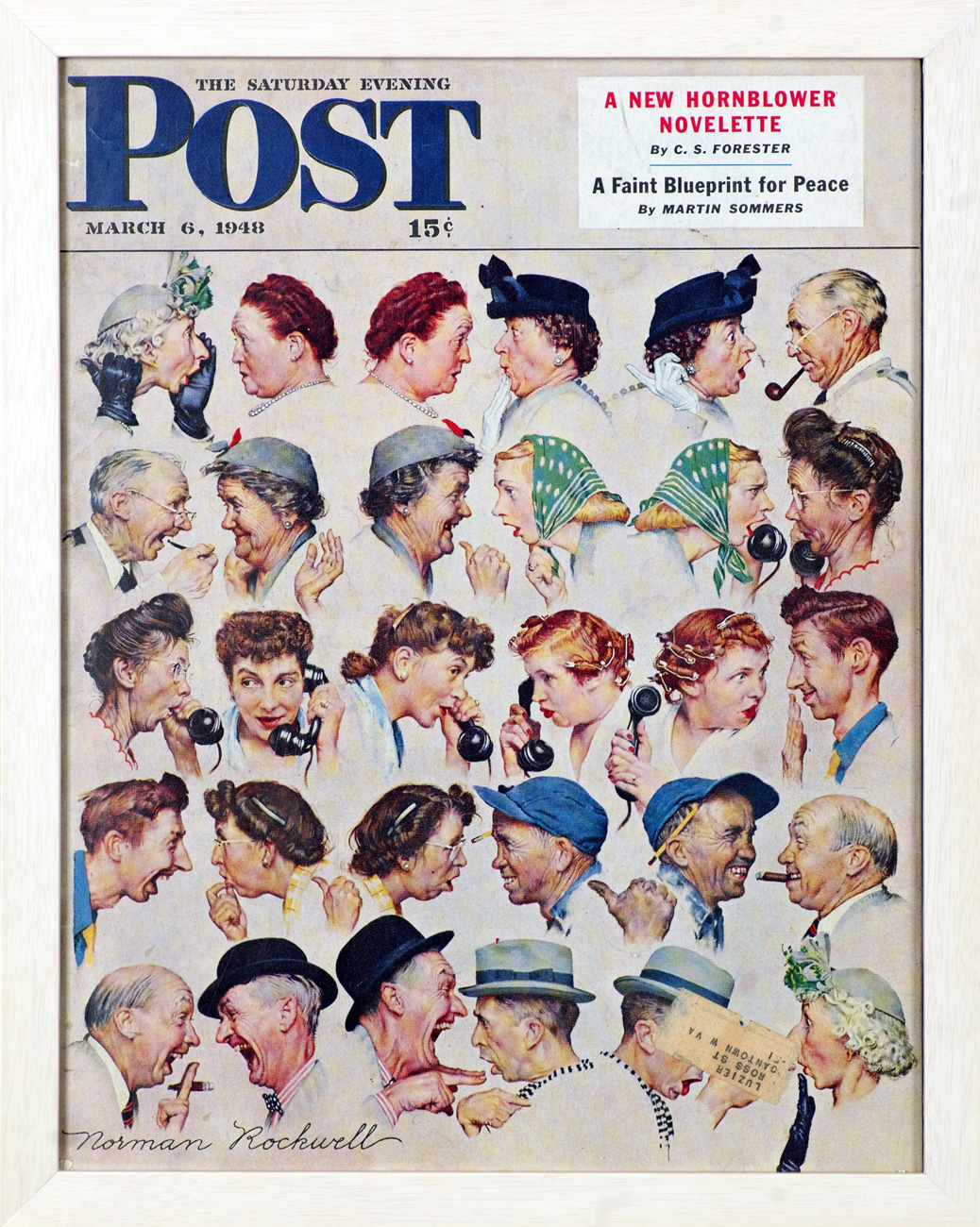

The void is twofold. It is not just the oblivion of sending one’s work to unknown parties and subsequently losing track of it. It is the equal oblivion of having even the known parties fail to comprehend the art in more than general terms. The contrast to other artists’ belief in a power of perfectly clear communication could not be starker. In 1948 in Arlington, Vermont, about a hundred miles from Woodstock, Norman Rockwell painted The Gossips (see Fig. 3)—a painting showing the transmission of a story from upper left to bottom right with absolutely no signal drift, no loss of message. The perfect circuit is an apt sign of Rockwell’s own powers of communication: his message is always loud and clear, and he can string together communities with what he says. But in Bright Light at Russell’s Corners, as in Ault’s other nighttime paintings of the solitary junction, the wires fade in and out.

Why did Ault portray this difficulty of communication? He felt that clear messages are vulgar and avoided them on those grounds. But there is something still more reserved about his paintings than that. Avoiding explicit messages, they risk—and seem to know they risk—an absolute quietness, so reserved, so withdrawn, that they all but invite a viewer to walk past them with hardly a look. When seen in the same gallery as the larger, bolder works of Edward Hopper (1882–1967), for example, Ault’s paintings retire. “I recalled how uningratiating his paintings looked, and austere, when hanging among others,” Louise remembered.13

The reticence, however, is far from a petulant withholding of moods and insights. It has rather the quality of a gift requiring some effort to find—some saving secret just off the beaten track. The paintings are like the waterfall Louise remembered she and her husband “had discovered unexpectedly on a walk, after we left the road to follow an old quarry trail and descended a ledge to wander below.” Like this waterfall, “actually close by the road but unsuspected, hidden from passersby,” Ault’s paintings would be “solitary and sublime,” unknown except to those who knew where to look.14 Ault conceived his paintings as secrets hidden in cool quiet, kept away from those who did not know or care how to look—the “wrong ones,” Robert Frost called them in those years15—but suggesting a meeting place, a convergence, where some saving wisdom would be revealed. Disdainful of showcasing their wonders, they offer quieter revelations.

And what are these revelations? What stands out in Bright Light at Russell’s Corners is the electric light. In one sense it is a Christian light, sign of private devotion, strange as this may seem to say about an artist who changed his middle name from Christian to Copeland and who professed to hate religion. Louise wrote of how her husband framed and hung a color reproduction of Sassetta’s Journey of the Magi in his studio (see Fig. 5), with “its dazzling star hovering close to earth, illuminating the earth” at lower right. Ault almost certainly saw the actual painting, given in 1943 to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where the small panel would have been among the “lovingly painted” Renaissance pictures with their “landscape backgrounds” that Louise recalled her husband pointed out to her.16 Sassetta’s star is an apt model for the large and eponymous street light in Bright Light, making the lonely crossroads a place of religious reverence and holy guidance. The light in Ault’s painting, a flower of grace illuminating no procession and no parade, lights a solitary path, a glowing compass that designs the dirt of the road no less than the planes of the barn, showing the way.

But the light is also that of someone who believes God is dead. Louise chose a quotation from Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) to epitomize her husband: “Unless there be chaos within, no dancing star is born.”17 The Russell’s Corners light is such a Nietzschean glow. Nietzsche’s light, in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, is autonomous and lonely, the sign of a person living by his own laws, “a star thrown out into the void and into the icy breath of solitude.” Nietzsche’s light, too, is hostile to an afterworld, a life after life, since “God is dead” but the light is a life-affirming power to those who have it, a lightning bolt of creative pleasure and passion. And it is a gift the passionate artist gives to others. “Goldlike gleam the eyes of the giver,” Zarathustra tells the townspeople at a crossroads before taking his leave.18

The giving comes at a personal cost, yes. The gift giver, made of light, envies the darkness, wishing that he too could be the night and receive “gifts of light” instead of only bestowing them. He rues his self-immolation, regretting that he lives only in his own light, “drink[ing] back into myself the flames that break out of me.” And he envies and hates those to whom he gives. “I should like to hurt those for whom I shine.”19 But his fierce and joyful independence was meant to be a path to those who find it.

Did Ault imagine his work would outlive him? When Ault fell into the flooded, swollen stream near their house as he walked home alone on the stormy night of December 30, 1948—they did not recover his body until five days later—“he must have felt helpless, an utter victim,” Louise thought. He had told her once that when birds die, that was all there was to it—“ping!”—and they were gone, and so it was for him the night he died, Louise thought: “He went ‘ping!’… hurtling into a universe that he knew well.” She thought too of how he would say “Here today and gone tomorrow” with a “would-be flippant smile.”20

Certainly Ault’s last painting of Russell’s Corners, August Night at Russell’s Corners, is literally his darkest and emptiest (Fig. 6). Painted a few months before his death and showing the vantage looking up the Rock City Road toward the vantage of Black Night, the first Russell’s Corners painting from five years earlier, the painting “seemed blacker than the others,” Louise wrote; “its black center deep, a void.”21 Proportionately, Ault devoted much more of the canvas to the empty sky, and it is the emptiest of all the Russell’s Corners paintings. Compared to it, the night sky in Black Night, for all its somber quiet, seems positively busy with designs—telephone poles, wires, barns, and the tree. In August Night there is instead a void as of outer space, “the universe that he knew well.” The lone street light appears as a sun beheld from the curved surface of a remote planet.

Yet all that night holds this sun as though for special keeping. The light is the most insistent thing in the painting, the part that looks directly out at us, amid all the reticence, the retreating and withdrawing. The sun counters the rapid rush of diminution along the Rock City Road, the feeling of dust and vanishing points. If the sun should stand out even in this darkest picture, then the same is true in all the Russell’s Corners paintings. And though these pictures are not illustrations of Nietzschean philosophy any more than they are of Christianity, and though the philosophy itself may seem overwrought to a more cynical and clinical temperament, there is nevertheless the fact that Ault’s cry of pain, as a gift, should glow with a splendor sufficient to make it an affirmation, a dancing star born from chaos. So do his scenes radiate with the perpetual order of these small suns.

To Make a World: George Ault and 1940s America is on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D. C., March 11 to September 5; the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, October 8 to December 31; and the Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia, Athens, February 18, 2012 to April 16, 2012

1 John Ruggles, “Ault of Woodstock,” Art News, vol. 48 (September 1949), p. 46. Housman’s words are from Poem XII (“The laws of God, the laws of man”) in Last Poems (1922; Mayflower Press, Plymouth, England, 1937), p. 18.

2 Louise Ault, “Remember a Thistle: A Novel (Factual),” p. 113 (collection of Maurice and Suzanne Vanderwoude). Louise wrote three separate but overlapping accounts of her life with her husband. “Remember a Thistle” and “George Ault: A Biography” (George Ault Papers, Archives of American Art) are unpublished. The third is Artist in Woodstock, George Ault: The Independent Years (Dorrance, Philadelphia., 1978). “Remember a Thistle,” though subtitled “A Novel,” contains hardly any information differing substantially from that contained in the two non-fiction accounts.

3 Louise Jonas, “Henry Mattson’s Philosophy: ‘I’ve Been Able to Paint—I’m Darn Lucky,’” Poughkeepsie Sunday New Yorker, December 20, 1942, p. 4A. Louise used her maiden name, Jonas, in her byline.

4 “Remember a Thistle,” pp. 164, 109–110.

5 Louise Jonas, “Spirit of Gothic Artists Alive Today in Alfeo Faggi, Sculptor,” Poughkeepsie Sunday New Yorker, June 13, 1943, p. 3A; and “Her Light Came to be Symbol of Courage,” ibid., November 21, 1943, p. 2A.

6 “Brief Chronology” and Susan Lubowsky Talbott, “George Ault’s Disquieting Vision,” in Eila M. Kokkinen, George Ault: The Woodstock Years (Woodstock Artists Association, Woodstock, N.Y., 2001), pp. 44, 18. For the specifics of Donald’s and Charles’s suicides in 1930 and 1931, see “George Ault: A Biography,” p. 17.

7 Philip Rahv, “The Cult of Experience in American Writing,” Partisan Review, vol. 7 (November–December 1940), p. 423. For Ault’s praise of Rahv, see George C. Ault, “Letters,” ibid., vol. 8 (March–April 1941), p. 159. Ault called Rahv’s essay and another one by Meyer Schapiro “top-hole.”

8 “Remember a Thistle,” pp. 127–128; “George Ault: A Biography,” p. 54.

9 Thornton Wilder, Our Town: A Play in Three Acts (Perennial, New York, 2003), p. 46.

10 Housman, Poem IX (“The chestnut casts his flambeaux, and the flowers”), in Last Poems, p. 15; Ault’s appreciation of the poem is in “Remember a Thistle,” p. 92.

11 “George Ault: A Biography,” p. 42.

12 George Ault to Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Lawrence, May 18, 1948, George Ault Papers, Archives of American Art, Washington, D.C.

13 “Remember a Thistle,” p. 163.

14 Artist in Woodstock, p. 150.

15 Robert Frost, “Directive,” in Steeple Bush (Henry Holt, New York, 1947), pp. 7–9. The poem first appeared in Virginia Quarterly Review, vol. 22 (Winter 1946), pp. 1–3.

16 “George Ault: A Biography,” p. 54; Artist in Woodstock, p. 14; “Remember a Thistle,” p. 123.

17 Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for All and None, trans. Walter Kaufmann (Modern Library, New York, 1995), p. 17 (where it is rendered as “One must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star”). The variant translation of this sentence, “Unless there be chaos within, no dancing star is born,” is the epigraph for “Remember a Thistle” and “George Ault: A Biography.”

18 Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, pp. 63, 74.

19 Ibid., p. 106.

20 “George Ault: A Biography,” p. 59; “Remember a Thistle,” p. 245.

21 “George Ault: A Biography,” p. 72.

Alexander Nemerov is Vincent Scully Professor and chair of the History of Art Department at Yale University. He is the curator of To Make a World: George Ault and 1940s America and the author of the accompanying catalogue. His most recent book is Acting in the Night: Macbeth and the Places of the Civil War.

Fig. 1. Black Night: Russell’s Corners by George Ault (1891–1948), 1943. Signed and dated

Fig. 1. Black Night: Russell’s Corners by George Ault (1891–1948), 1943. Signed and dated Fig. 2. Studio Interior by Ault, 1938. Signed and dated “G.C. Ault ’38” at lower right. Watercolor and graphite on paper, 20 by 23 ½ inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D. C., transfer from the Museum of Modern Art.

Fig. 2. Studio Interior by Ault, 1938. Signed and dated “G.C. Ault ’38” at lower right. Watercolor and graphite on paper, 20 by 23 ½ inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D. C., transfer from the Museum of Modern Art. Fig. 3 The Gossips by Norman Rockwell (1893–1978), tear sheet of the cover of the Saturday Evening Post for March 6, 1948. 13 ⅝ by 10 ⅝ inches. Norman Rockwell Museum Archival Collections ©1948SEPS: Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis; on view at the Brooklyn Museum of Art.

Fig. 3 The Gossips by Norman Rockwell (1893–1978), tear sheet of the cover of the Saturday Evening Post for March 6, 1948. 13 ⅝ by 10 ⅝ inches. Norman Rockwell Museum Archival Collections ©1948SEPS: Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis; on view at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. Fig. 4. Bright Light at Russell’s Corners by Ault, 1946. Signed and dated “g.c. ault ’46” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 19 ⅝ by 25 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Lawrence.

Fig. 4. Bright Light at Russell’s Corners by Ault, 1946. Signed and dated “g.c. ault ’46” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 19 ⅝ by 25 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Lawrence. Fig. 5. The Journey of the Magi by Sassetta (Stefano di Giovanni; active 1423–1450), c. 1433–1435. Tempera and gold on wood, 8 ½ by 11 ¾ inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Maitland F. Griggs Collection, bequest of Maitland F. Griggs; Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Fig. 5. The Journey of the Magi by Sassetta (Stefano di Giovanni; active 1423–1450), c. 1433–1435. Tempera and gold on wood, 8 ½ by 11 ¾ inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Maitland F. Griggs Collection, bequest of Maitland F. Griggs; Metropolitan Museum of Art. Fig. 6. August Night at Russell’s Corners by Ault, 1948. Signed “G.C. Ault” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 18 by 24 inches. Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha.

Fig. 6. August Night at Russell’s Corners by Ault, 1948. Signed “G.C. Ault” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 18 by 24 inches. Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha.