Samuel Yellin received what would prove perhaps his single most important early commission in 1914, for the Frank Augustus Seiberling estate in Akron, Ohio. The creative challenges and sheer magnitude of this effort set a new standard for Yellin and showed his singular ability to design and create a fully integrated approach to hardware for a devoted architect and client. Born in 1859, Seiberling was an inventor and leading Midwestern industrialist who became famous for co-founding the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company in 1898 and the Seiberling Rubber Company in 1921. The son of a German immigrant entrepreneur, Seiberling was educated at Heidelberg College in Tiffin, Ohio, before joining the J. F. Seiberling Company. He worked as secretary and treasurer of his father’s farm machinery manufacturing business, which produced the first reaping machines. The young Seiberling demonstrated his own knack for invention when he created a twine binder that tied grain bundles with a bowknot.1 In 1887 he married Gertrude Ferguson Penfield.

Amidst the panics of the 1890s, Frank Seiberling found himself jobless in 1898, nearly forty years old and supporting a wife and three children. He learned of an available strawboard factory in East Akron, which he purchased for $13,500, with a down payment of $3,500 provided by a brother-in-law.2 Within just a few days he had decided to set up a rubber business, named it for Charles Goodyear, the man who had discovered vulcanization but died penniless almost forty years earlier, and began selling stock. In 1906 Seiberling became president of the company, a position he held until 1921. He worked tirelessly, playing an essential role in developing the company and the town of Akron, which became known as the “rubber capital of the world.”

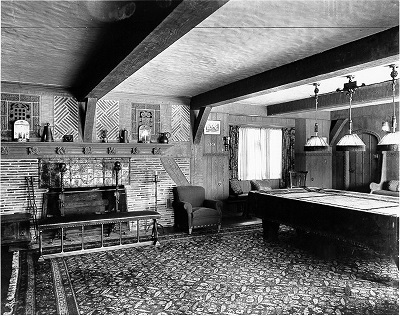

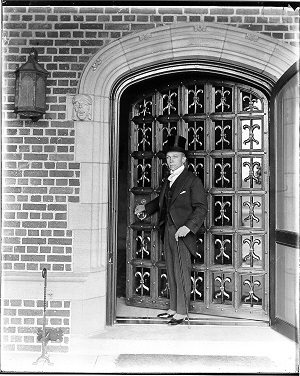

The estate Seiberling and his wife developed on Akron’s northwest side would be known as Stan Hywet (“stone quarry” in Old English) Hall. Built between 1912 and 1915, the English Tudor revival mansion is a masterpiece of the style and served not only as the family seat but also as the location of business meetings and an “international stage for well-known figures in music, the arts and politics.” 3 Charles S. Schneider, the architect, was given a budget of $150,000, and he and the Seiberlings immersed themselves in early English design, traveling to England to visit well-known country estates, including Ockwells Manor in Berkshire, Compton Wynyates in Warwickshire, and Haddon Hall in Derbyshire. In addition, the Seiberlings engaged Boston landscape architect Warren H. Manning and New York interior decorator Hugo F. Huber, the latter of whom forged a close relationship with Gertrude Seiberling, often traveling, dining, and shopping with her. In this context of architecture and interiors steeped in European antiquity, it is unsurprising that Yellin’s modernized medieval designs dovetailed so seamlessly. Because of the significance and creativity of the works created by Samuel Yellin Metalworkers for this commission, careful analysis of his participation in this project reveals much about his artistic methods and business practices.

Initially, bids from four contractors were received for “ornamental iron companies on the work of making and erecting the entrance gates”—William H Jackson Company, W. S. Tyler Company, Winslow Brothers Company, and John Williams, but not Yellin. 4 Williams was clearly the choice of the architect, who enclosed a “sample of iron showing the hand hammered finish.” For some reason, Schneider acknowledged, Seiberling was uncomfortable with making “the investment in the gates at this time” and instead chose to go ahead with the stone piers for the entrance but using temporary wooden gates.

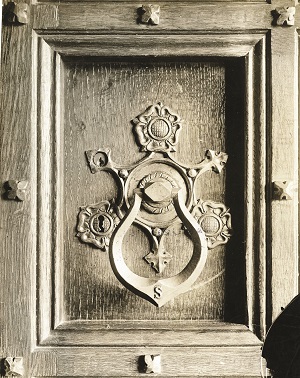

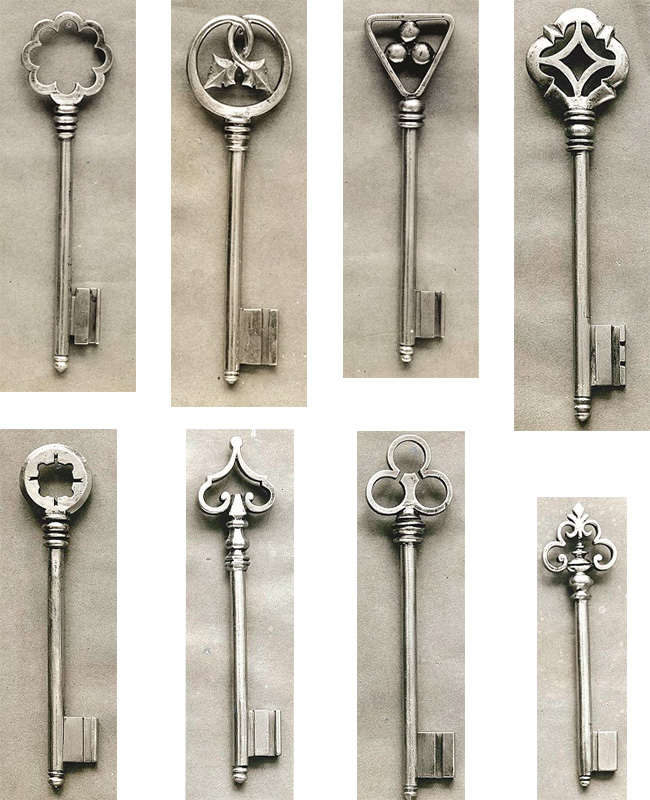

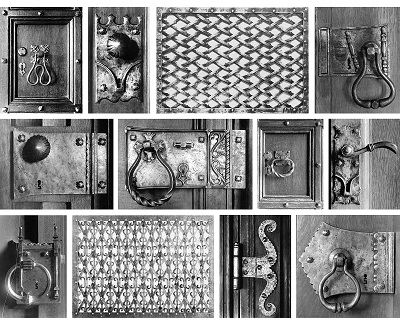

By the middle of 1913, Schneider had requested a “bid on this work from Samuel Yellin,” 5 and by May of the following year Yellin seems to have been the choice for all the decorative hardware under discussion here. Schneider reported to Seiberling on May 27, 1914, that “special Yellin work has been figured for the entire first floor, including the copper hood of Billiard Room, the grilles in the panels of the front door, iron straps on some of the beams of the Billiard Room etc.” In addition, Yellin was to supply “work in the upper stories where hardware of that type is desirable, such as Bed room ‘A,’ the boys’ rooms and the lower Guest room” and special hardware for all the exterior and interior metal casement windows and French doors. In the same letter Schneider notes that Yellin had also been solicited for estimates for thermostat fronts and electrical push-button and receptacle plates, to take the place of the “cheap stamped variety gotten out by the Johnson Company,” and had been encouraged to “make them a work of art.”

Yellin was scheduled to meet with Schneider and Seiberling during the second week of November 1914, to “report on quantities, costs and designs of special hardware,” 6 but for some reason this meeting did not occur and Yellin complained that he had gone to “a considerable amount of trouble and expense, with the aim of securing this work.”7 One of Seiberling’s objections to Yellin’s proposed involvement had nothing to do with the artistic merit of his work. Instead his concerns stemmed from Yellin having suggested that he would need a local installer and manager of ironwork for Stan Hywet.8 Schneider suggested that they meet with Yellin in New York or Philadelphia: “It might be preferable to see him right in Philadelphia so we could go to his shop. I am keenly interested in this man and his work and would like to see how the work is done. There is no doubt in my mind but that he can do this work better than anybody else in this country and perhaps if we have such a conference with him we may be able to come to some kind of an agreement which will be more satisfactory to you.”9

Seiberling replied on November 21 that he would be “glad” to meet Yellin in New York, and “after we are ready to determine how much we will do with him you can determine whether it is advisable to stop off and see his work.” The letter indicates that Seiberling had decided that he wanted to give Yellin “some of the work in lower rooms,” but could not “stand such a cost as he outlined in his tentative proposal.” By December H. F. Huber and Company’s work on the interior was moving forward quickly. Expenses were mounting quickly too: Huber billed $2,350 on December 18 for “installation of the antique woodwork for Bedroom A” and for the “new base, cornice, change in the mantel and window treatment.”10

In early 1915 the Seiberlings were off to England for further research and to shop for art and antiques.11 On their return, by April, the art and decoration schemes for Stan Hywet were running along quickly, with Huber leading the charge. He advised Mrs. Seiberling that “there would take place at the American Art Galleries this week

the sale of paintings belonging to the late Theron J. Blakeslee, probably the most famous English picture dealer.”12 He encouraged her to alert her husband and encouraged them to participate in the sale. The couple did so, acquiring works by Sir Thomas Lawrence, Sir Joshua Reynolds, George Romney, John Hoppner, and Sir Henry Raeburn, totaling over $22,000.13 In May Huber proposed the purchase of tapestries totaling more than $42,000 through French and Company in New York, and several of these, too, were acquired.14

Apparently soon after finally contracting Yellin for the work at Stan Hywet, by June 1915, Seiberling became impatient to receive the completed order. He wrote to Yellin on June 18 that he was “naturally getting somewhat anxious as to the progress of the work, since we are approaching the time when it must be installed.” Yellin replied quickly on June 21 that “the work for your new residence is progressing nicely….I am working on the Hardware, designs of which had been approved by Mr. Schneider, and I am continuously sending to Mr. Schneider other designs for his approval.” As to the all-important front gates, Yellin wrote that the “working drawings for same will be forwarded to Mr. Schneider some time this week for his criticism.” To speed things along Yellin promised that “the actual work will be started immediately upon the return of these drawings.” Still, attempting to avoid unrealistic expectations, he wrote, “I am trying very hard to execute real iron work, and my intention is far from sacrificing the artistic quality in order to gain in time.”

Things certainly seem not to have raced forward over the summer, as on September 21 Yellin wrote to Seiberling that “in about two months I will be able to have these gates done….I am not simply following the drawing,” he wrote, “but constantly playing around and experimenting with all the work I am doing for you in order to obtain real artistic results.” While the hardware shipments had commenced by this point, Yellin again begged indulgence for delays, calling attention to his “characteristic touches in every piece of hardware,” which made it impossible “that many men can be kept busy on it, and for that reason the execution of the same takes considerable time.”

Seiberling continued to indulge Yellin’s artistic pursuits as the work continued to get later and later for delivery, stating that he regretted to learn that the gates would “not be finished until December, though I do not want them a day sooner than you are satisfied that they can come to me with the best art that you are able to put into them.”15 The remainder of the order was more urgent, he continued, as he was seeking to “move in not later than the first of December.” Yellin immediately reassured his client that “I am using all my efforts to get out the work for your residence as fast as possibly can be done without injuring the quality of the work” and explaining that “there are hundreds of small details which cannot be simply made like the drawing; there are many improvements to be made which can be neither shown on paper nor explained in writing.”16

Confidence in Yellin’s work, despite the delays, was apparent in Seiberling’s approval of further work for Bedroom C—“ornamental iron grilles for door #215… at an additional cost” of $210.17 Yellin received his first payment of $1,250, against the original contract amount of $10,245 on October 13, 1915.18 Schneider visited Yellin in mid-November and reassured Seiberling that he had “practically his entire force of men working on the contract.”19 Strap hardware and hinges were to be shipped within “a week’s time,” with the architect and Yellin working out a schedule of priorities. Schneider visited Yellin again in early December and was disappointed to find that “there was not much…that was actually completed and ready for shipment.”20 Seiberling complained that Schneider’s report was “decidedly unsatisfactory, as it is not in any sense specific and leaves me up in the air as to when he will come through.”21 Even so, at this point Seiberling and the architect approved adding work for the “Hospital” room to Yellin’s contract.

Yellin reassured his client in a letter of December 6 that he had shipped “to your residence hardware for sixteen doors, such as locks, latches, bolts, etc.,” with “the same amount of hardware if not more,” to follow. Still, delays for other aspects of the ironwork continued. As Schneider wrote to Seiberling on December 15, “I would judge that Mr. Yellin will not have any of his wrought iron grilles and register faces at the building by Christmas time.” Meanwhile, Mrs. Seiberling’s decoration of the interiors continued in early 1916, including an order for various pieces of walnut and cane furniture from Thonet Brothers in New York and payments for another tapestry and “two cantonnieres and two needlework arm chairs” acknowledged by French and Company on February 19.22 On the same date billing was submitted to Huber by Schmitt Brothers of New York for an “Antique oak Jacobean bed stead, set of original Jacobean bed hangings, Queen Anne trivets and Sussex iron grate” for the Seiberling estate.23

In mid-February 1916 Schneider was feeling “more and more discouraged about the progress” Yellin was making, deeming it “quite necessary to take another trip to Philadelphia to brace him up.”24 Shortly afterwards, Yellin traveled to Akron and told Seiberling that he was “deeply impressed with all the charming details” he saw at Stan Hywet and his “great pleasure” in seeing his own “beautiful work incorporated” in this “extraordinary house.”25 He assured Seiberling that “all of the remaining work is now under way.” The gates remained the outlying schedule date. As Schneider described to Seiberling on April 24, “The last information about the progress on these gates reached me this morning and is to the effect that he does not believe he can have them in place before June 1st.” Seiberling’s response to this matter a day later was quite simple: “As to Yellin I have given up on him and am resigned to the view that the gates will come whenever he is ready to furnish them.”

Despite Seiberling’s resignation, the architect remained passionate about getting the work completed, writing on May 24 that “Mr. Yellin reports that the gates are nearing completion and will probably be ready for shipment in a week or so.” His anticipation turned to excitement after visiting Philadelphia, where he gave “final inspection to the gates” and reported to Seiberling on May 27, “I am very enthusiastic about them; they are going to be very beautiful and Yellin is doing a splendid piece of work.” As the hardware was being completed and installed along with work on the gates, the interior of the house continued to be outfitted with the finest furnishings courtesy of Huber and Company. An accounting dated May 1, 1916, and totaling more than $275,000 included American paintings, “Indian” and “Oriental” rugs, English and American furniture, tapestries, lighting fixtures and andirons by Caldwell, Sterling Bronze, and Black and Boyd, painting and decorating services, and much more.26

Yellin’s gates were finally installed in late May or early June, and Yellin did not wait long to ask Seiberling about his satisfaction with the work. He suggested in a letter of June 20 that he had exerted himself “in the utmost to obtain the best results possible” and “considered it a great honor to have the opportunity of doing this work,” but he was also so bold as to ask “whether it would be possible and convenient for [Seiberling] to speak in [Yellin’s] behalf to Mr. S. G. Carkhuff of the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company,” who was apparently also building a residence in Akron. Truly a study in Yellin’s early aptitude and challenges in working with clients and architects, his commission for Stan Hywet stands as magnificent testimony to his creativity and talent.

1 New York Times, June 12, 1911, p. 1. 2 Information from tireindustry.org/ hall-fame and goodyear.com. 3 Many details about the history of the house are from the website stanhywet.org. 4 Charles Schneider to Frank A. Seiberling, June 27, 1913. Unless otherwise noted, all letters quoted in this article are in the archives at Stan Hywet Hall. 5 List of Matters to be taken up with Mr. and Mrs. Seiberling, copy in Stan Hywet Hall archives. 6 Schneider to Seiberling, November 5, 1914. 7 Yellin to Schneider, November 18, 1914. 8 Schneider to Seiberling, November 19, 1914.9 Ibid. 10 Invoice from H.F. Huber and Company to Mrs. F. A. Seiberling, December 18, 1914, copy in Stan Hywet Hall archives. 11 Schneider to Seiberling, January 15, 1915. 12 H.F. Huber and Company to Mrs. F. A. Seiberling, April 19, 1915. 13 Receipt for purchases by F. A. Seiberling from American Art Association, New York, April 1915, copy in Stan Hywet Hall archives. 14 Huber and Company to F. A. Seiberling, May 27, 1915, ibid. 15 Seiberling to Yellin, September 23, 1915. 16 Yellin to Seiberling, September 25, 1915. 17 Schneider to Seiberling, September 29, 1915. 18 Yellin to Seiberling, dictated but signed in his absence by Joseph Winthrop, October 15, 1915; see also Certificate No. I, Charles Schneider to F. A. Seiberling, Stan Hywet Hall archives. 19 Schneider to Seiberling, November 13, 1915. 20 Ibid., December 3, 1915. 21 Seiberling to Schneider, December 4, 1915. 22 Invoice, Thonet Brothers, Bent Wood Furniture, through Mr. Huber, January 22, 1916; and P.W. French and Company, to H. F. Huber, Esq., February 19, 1916, both Stan Hywet Hall archives. 23 Schmitt Brothers invoice, February 19, 1916, ibid. 24 Schneider to Seiberling, February 17, 1916. 25 Yellin to Seiberling, March 15, 1916. 26 Report and inventory of purchases sold to F. A. Seiberling, H.F. Huber and Company, May 1, 1916, Stan Hywet Hall archives.

JOSEPH CUNNINGHAM is the curatorial director of the Leeds Art Foundation and the author of a forthcoming monograph on Samuel Yellin.