Work serves as a foundation for the philosophy of self-improvement and social mobility that undergirds this country’s value system. It influences how Americans measure their lives and how they assess their contributions to society. Yet work can be something imposed upon people: it can be exploitative, painful, and hard.

The Sweat of Their Face: Portraying American Workers, a new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, presents a powerful visual history that aims to reinscribe the important roles that laborers have had in shaping the United States since the colonial era. Historic images of newsboys on city streets, mill girls in factories, and builders in midair represent a mere sampling of the extraordinarily diverse depictions that compose the exhibition. The approaches and circumstances of the portrayers vary as much as the subjects they chose to—or were instructed to—portray. Nevertheless, when seen together, the selected representations illuminate the tendency in American art to modify the European portrait tradition. In the United States, artists and fellow laborers have consistently stood behind cameras and in front of easels to promote the legacies of under-recognized workers. It is these specific individuals who continue to inspire progress and innovation with the sweat of their face.

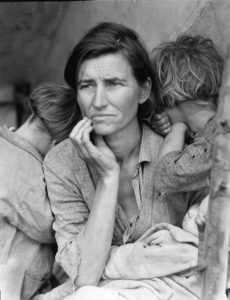

The women workers in the exhibition include an enslaved woman called Miss Breme Jones, a seamstress named Alma, a migrant worker named Florence Owens Thompson (the face of Dorothea Lange’s iconic Migrant Mother), a custodial worker named Ella Watson, and a coal miner named Linda Norberg. Despite the risk of invisibility brought upon them by the challenging working conditions these women faced, they are honored by the artists in portrayals that evoke strength as well as empathy. Along with other representations of women workers on view in the exhibition, they reveal a deep connection between artist and subject as workers, while pushing the genre of portraiture in new directions. In contrast to the more formal, commissioned portraits that comprise the National Portrait Gallery’s permanent collections, the representations of working women and men in Sweat of Their Face in many ways push portraiture into the mode of activism, making visible the overlooked and often unseen faces who built this country.

Child Labor, c. 1908 by Lewis Hine (1874 – 1940), 1908. Gelatin silver print, 14 by 15 inches. Bank of America Collection.

In Child Labor, c. 1908, sociological photographer Lewis Hine used his camera to make his audience “so sick and tired of the whole business that when the time for action comes, child labor pictures will be records of the past.” As a member of the National Child Labor Committee devoted to abolishing child work, Hine traveled across the United States to document a practice that was beginning to trouble and outrage many. Through his poignant documentary photographs, he brought the terrible truths of child labor to the attention of the American people. Hine carefully recorded information about the children he photographed on the back of each print. On the reverse of this photo, he wrote: “Sadie Pfeifer, 48 inches high, has worked half a year. One of the many small children at work in Lancaster Cotton Mills. Nov. 30, 1908. Location: Lancaster, South Carolina.”

Alma Sewing by Francis Hyman Criss (1901–1973), c. 1935. Oil on canvas, 33 by 45 inches. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia, purchase with funds from the Fine Arts Collectors, Mr. and Mrs. Henry Schwob, the Director’s Circle, Mr. and Mrs. John L. Huber, High Museum of Art Enhancement Fund, Stephen and Linda Sessler, the J. J. Haverty Fund, and through prior acquisitions.

Francis Hyman Criss was one of many artists commissioned by the Federal Art Project during the Great Depression. Under President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, laborers, including artists, received government support to alleviate the devastation caused by the stock market crash of 1929. As the victims most affected by the economic crisis, middle and lower-class workers were a subject of interest for Criss and many of his contemporaries. In this painting, an African-American seamstress diligently engages in her trade. Criss chose to insert himself into the painting by including his reflection on the lamp in the scene. With this gesture, he declared himself and other artists—like the seamstress—important yet under-appreciated members of the workforce.

Young Jewess Arriving at Ellis Island by Hine, 1905. Gelatin silver print, 10 by 8 inches. Courtesy Alan Klotz Gallery / Photocollect, Inc., New York.

Frank Manny, an important education reformer in the Progressive Era, hired Lewis Hine to teach at the Ethical Culture School in Manhattan. Manny provided Hine with a five-by-seven-inch view camera, a tripod, glass negatives, and flash powder, and encouraged him to use the camera as an educational tool. Together, they went to Ellis Island to capture images of immigrants arriving in the United States. Manny told Hine that he wanted his students to have the same regard for Ellis Island that they had for Plymouth Rock. The caption Hine published with this portrait of a young Jewish woman was taken from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass: “Inquiring, tireless, seeking what is yet unfound /. . . . /(But where is what I started for so long ago? / And why is it unfound?).” By photographing his subject at eye level as she gazes directly into his lens, Hine emphasizes his subject’s individuality rather than her type. In its haunting beauty and fragility, the image conjures a vision of what would assuredly be a difficult life ahead as the woman joined the workforce. There is, Hine wrote to Manny, “a crying need for photographers with even a slight degree of appreciation & sympathy.”

Woman Cleaning Shower in Beverly Hills (after David Hockney’s Man in Shower in Beverly Hills, 1964) by Ramiro Gomez (1986–), 2013. Acrylic on canvas, 36 inches square. Private collection.

Ramiro Gomez frequently obscures the faces of his subjects to draw attention to the working-class Latinos in his Los Angeles community, who are too often marginalized and ignored. At the same time, his obscuring of facial features lends his subjects an everyman or everywoman quality. In this painting, a housekeeper is shown scrubbing the tiled walls of her wealthy employer’s shower, a composition based on a painting by David Hockney. She is turned away from the viewer, with her back bent and her head slightly bowed, stripping her of her individuality. The woman’s posture conjures the act of praying or even weeping. Recent data compiled by the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that the average house cleaner earns around $20,000 annually, which is less than half the national average income for individuals. Gomez, who has worked as a nanny to support his art practice, has said, “I’m painting my own mother. I’m painting about my dad. I’m painting about myself.” As autobiographical work, Gomez’s appropriations carry an urgent, activist message, a call to make the invisible visible and in the process highlight the stories of immigrant workers whose voices have been excluded from dominant narratives of history or who have been ignored by current politicians.

Washington, D.C., Government Charwoman (American Gothic) by Gordon Parks (1912–2006), 1942. Gelatin silver print, 43 ⅝ by 31 ⅞ inches. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Corcoran Collection (The Gordon Parks Collection).

Gordon Parks, the first African-American staff photographer for Life magazine, captured this image after joining the Farm Security Administration’s (FSA) photographic team. His work with the FSA (1942–1943), combined with his subsequent employment with the Office of War Information (1943–1945), allowed him close access to workers. As a government worker himself, and as someone who had taken on odd jobs throughout his life, Parks could identify with his subjects and viewed them through an empathetic lens. Parks met the woman in this photograph, Ella Watson (life dates unknown), in a government building. Holding a mop and standing before an American flag, her pose recalls Grant Wood’s iconic painting American Gothic (1930). For Parks, this visual echo was an expression of the inequality experienced by African-American workers. His own experience of discrimination in Washington, DC, and his desire to expose the prejudice that pervaded the nation’s capital motivated him to create a series of eighty-five portraits of Watson that charted her daily life.

The Jolly Washerwoman by Lilly Martin Spencer (1822–1902), 1851. Oil on canvas, 24 ½ by 17 ½ inches. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, purchased through a gift from Florence B. Moore in memory of her husband, Lansing P. Moore, class of 1937.

Artist Lilly Martin Spencer studied under John Insco Williams in Ohio. After training with him, she moved to New York City, where she supported her husband and thirteen children by painting. Spencer made a specialty of painting household scenes, including servants. An admirer of mid-nineteenth-century German genre painting, she channeled a similar realism in The Jolly Washerwoman, a portrait of a jovial domestic worker. Here, Spencer illustrates her servant doing laundry with both effort and delight, as evidenced by the thin film of sweat on her skin and her sensationally wide grin. Spencer’s domestic subjects usually appear strong and in command of their tasks, and are often shown engaging the viewer with a clear gaze and, sometimes, a startling directness.

Old Mill (The Morning Bell) by Winslow Homer (1836–1910), 1871. Oil on canvas, 24 by 38 ⅛ inches. Yale University Art Gallery, bequest of Stephen Carlton Clark.

In Old Mill (The Morning Bell), Winslow Homer, who had been an artist correspondent for Harper’s Weekly during the Civil War, chose to overlook the harsh realities of millwork when he made this painting. The artist offered relief to those feeling apprehensive about the country’s new industrial landscape by creating an idyllic, pastoral scene that evokes nostalgia for the antebellum period. Walking away from the somberly dressed rural women on the right, a lady in colorful, fashionable “town” attire ascends to her job in the mill. She symbolically departs from an agrarian past and enters an industrialized present, perhaps taking the path toward heightened social and economic status for women. The mill’s chiming bell indicates the start of a workday and the beginning of a new, commercial America. Critics often focused on Homer’s choice of subject matter, and Old Mill was received harshly for what was perceived to be its unclear purpose. The figures were said to lack gracefulness, and Homer was accused of using the scene as an excuse to paint a landscape. While the artist’s choice to make work the subject of the painting was not a focus of contemporary critical discourse, it is the theme he expanded upon in a later engraving based on this painting; in that print, male and female mill workers are included to emphasize the lifelong toil brought on by industrialization.

Miss Breme Jones by John Rose (1752/3–1820), c. 1785–1787. Watercolor and ink on wove paper, 7 ½ by 6 ⅛ inches. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, Williamsburg, Virginia, museum purchase, the Friends of Colonial Williamsburg Collections Fund.

This delicate watercolor pictures Breme Jones, midstride and in profile, clad in an apron and a blue-striped dress. In the top left section of the sketch, a faded inscription reads, “Grave in her steps / Heaven in her eye’s / And all her movement / Dignity and Love.” These four phrases are based on a passage from John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost (1667) referencing Adam’s adoration of Eve. It is worth noting that Milton’s word “Grace” has been changed to “Grave” in this interpretation. John Rose, a South Carolina plantation owner, appropriated Milton’s affectionate words for this portrait of Jones, a slave who may have helped him raise his children after his first wife died. Miss Breme Jones evidences one of the many tragedies of the period in that the denial of an enslaved person’s very humanity was contradicted in reality by its obvious existence.

Lathe Operator Machining Parts for Transport Planes at the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation Plant, Fort Worth, Texas by Howard R. Hollem (d. 1949), 1942. Digital inkjet print from original 4-by-5-inch color transparency. Library of Congress, Washington, DC, Prints and Photographs Division.

Following the US entrance into World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Office of War Information, an agency that promoted patriotic activities while documenting and releasing news of the war. Staff photographer Howard R. Hollem contributed to this effort with images of men and women involved in wartime industries that emphasize their good work and evoke a sense of military preparedness and heroism. The subject of this photograph is one of the many women who took on jobs during the war, when the labor force grew by 6.5 million women as men left to join the military. After the war, most women left their factory jobs, and men returned to their former positions, but some women continued working in the booming postwar economy, often entering traditional female professions such as secretarial work and nursing.

Cutting Squash (Leah Chase) by Gustave Blache III (1977–), 2010. Oil on panel, 8 ½ by 10 inches. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, gift of the artist in honor of Richard C. Colton Jr.

Leah Chase (1923–) is reverentially referred to as the “Queen of Creole Cuisine.” In 1945 she married jazz musician Edgar “Dooky” Chase Jr. and joined the family restaurant business in New Orleans. By the 1960s Dooky Chase’s Restaurant was famous for Leah’s recipes and also as a gathering spot for prominent civil rights activists, including Martin Luther King Jr., who would join local leaders for strategy sessions over meals upstairs. Native New Orleans artist Gustave Blache III made a series of small portraits documenting Chase in the kitchen. His intimate genre scenes convey an immediacy that captures Chase’s tireless work ethic from a variety of perspectives and angles.

Destitute Pea Pickers in California. Mother of Seven Children. Age 32. (“Migrant Mother”) by Dorothea Lange (1895–1965), 1936. Gelatin silver print, 13 ¼ by 10 ⅜ inches. Library of Congress, Prints and

Photographs Division, gift of the photographer.

Destitute Pea Pickers in California. Mother of Seven Children. Age 32. (“Migrant Mother”) by Dorothea Lange is one of the most famous photographs of the twentieth century. While on assignment for the Farm Security Administration, a government program formed during the Great Depression to raise awareness of rural American poverty, Lange visited a pea-picking camp in Nipomo, California, and captured this image of Florence Owens Thompson (1903–1983), a widowed mother and itinerant farmer. Though reluctant to have her picture taken for fear of being showcased as a specimen of poverty, Thompson eventually relented, believing the image might benefit those in similar situations. After capturing five exposures of the woman with her clinging children, Lange showed the photographs to her supervisor, which in turn led authorities to send aid to the pea-pickers’ campsite. This image, widely distributed in newspapers and magazines, reminds us of the economic turmoil and resilience of American workers during the Great Depression.

Brightness All Around by Janet Biggs (1959–), 2011. Still image from a single-channel, high definition video with audio. Courtesy of Connersmith, Washington, DC.

Brightness All Around is part of feminist artist Janet Biggs’s Arctic Trilogy, a series of videos filmed in the Arctic between Norway and the North Pole. Biggs describes her larger body of work as exploring identity with a focus on how we navigate the limits imposed by society while “trying to push past those limits.” In this video she tracks Linda Norberg (life dates unknown), a coal miner and machine operator who dons protective gear as she plummets into the earth in one of the coldest parts of the world. The intense physical and psychological strain of this work presents a perfect subject for Biggs, whose videos often chronicle extreme activities. In juxtaposing Norberg’s dangerous, even life-threatening job with the glamorous performance of underground singer Bill Coleman, whose lyrics address near-death situations, Biggs accentuates Norberg’s determination, fearlessness, and inner strength.

Parts of this article were taken from the author’s contributions to the exhibition catalogue for The Sweat of Their Face: Portraying American Workers, on view at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery to September 3, 2018. npg.si.edu

DOROTHY MOSS is curator of painting and sculpture at the National Portrait Gallery.