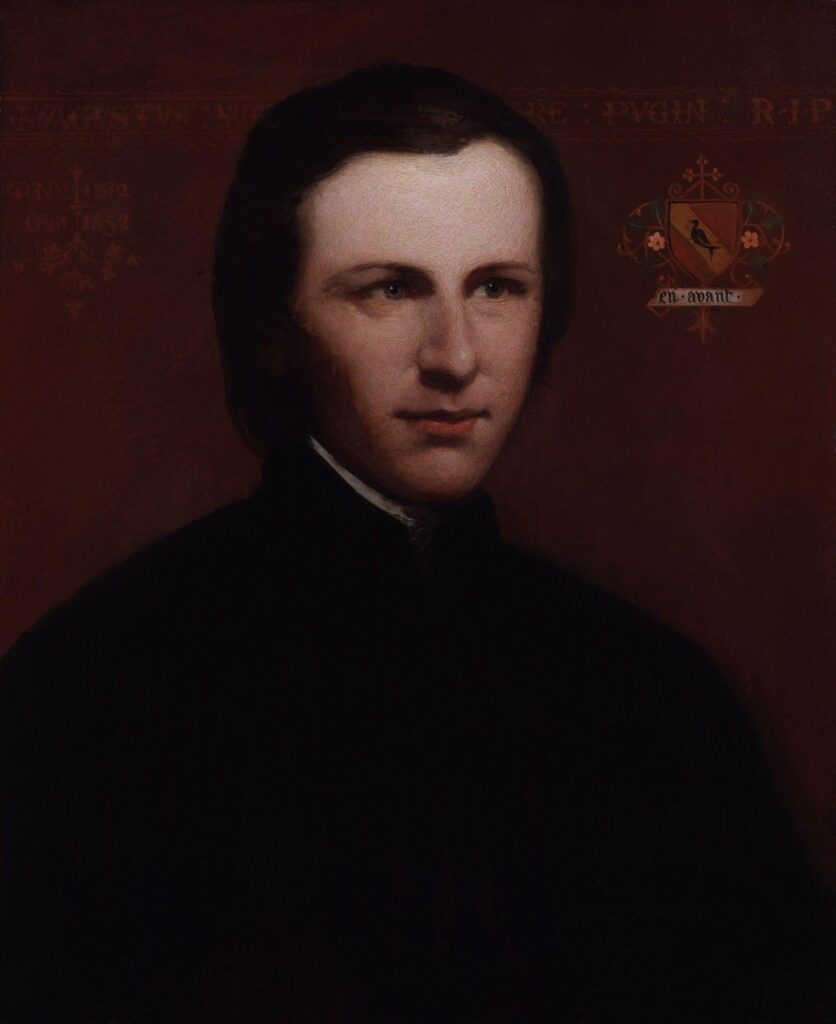

As the boy, suspended from a rope tied around his middle, was lowered through a hole in the roof of the church, past soaring trusses and arches, his eyes slowly grew accustomed to the dimness. Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin’s father held the other end of the rope, gently depositing his son on the floor of an ancient Gothic church near Rouen, France. The church had weathered the storm of the French Revolution—with its sanctioned dechristianization—remarkably well, and the boy could not help but be impressed with the handicraft of the pious men who had built the structure nearly four centuries before. He would spend the rest of his life evangelizing on behalf of what he saw there.

A commercial illustrator who fled the French Revolution for England, the elder Pugin, Auguste Charles (1762–1832), had belayed his son and pupil through the roof of the church so that he might gain a better sense of the splendid engineering and design, down to the minutest details. Pugin was himself a proponent of reviving the long-out-of-fashion Gothic style that characterized Western European architecture from the twelfth to the sixteenth century, and the lessons on that subject that he would give to his son began early. When Pugin was six years old his parents took him to Lincoln Cathedral, one of the finest examples of Gothic architecture in the world. At age nine Pugin produced his first Gothic-inspired sketch of a proposed building, proudly inscribing it “my first design.” Less than a decade into his life, the Gothic style had already sunk its roots deep in his mind.

Born in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars, Pugin grew up in a time of seismic changes. The French Revolution of a generation before had called into question certain foundational ideas and elements of the Western European worldview. It was like gravity had suddenly been switched off and the world turned upside down, leaving no one able to predict what tomorrow would look like. Pugin was raised on a steady diet of family tall tales, one of which had his father crawling out of a heap of corpses thrown in a pit near the Place de la Bastille, swimming across the Seine, and escaping to England. If our bedtime stories shape our worldview, this was one hell of a penny dreadful.

For the majority of his childhood Pugin worked as his father’s assistant, and when he was twelve they traveled together on a sketching trip to northern France. They visited Gothic sites around Rouen, and Pugin strove to come to grips with the rules of engineering behind the buildings he so admired—this is what led to him hanging suspended through a hole in the roof of that ancient church. Young Pugin would take to heart the lessons he learned from that eccentric exercise and others like it. Theory and facade had their place, but how the object—be it a building, a plate, a table, or a clock—felt in the hand, or stood up against gravity in the real world, mattered most of all.

Over the next two decades A. W. N. Pugin developed from a boy spelunking in the manmade caverns of Europe to an energetic proponent of the Gothic revival style. Today, he remains one of the great heroes of the British cultural pantheon.

When some hear the term “Regency Britain” their minds immediately go to the splendor on display in such TV shows as the Netflix hit Bridgerton. But the majority of British citizens in the nineteenth century did not enjoy the London Season—for most it was a time of poverty and squalor. There was a pervasive feel-ing that something precious had been lost, that a golden age had winked out without anyone noticing. As Pugin grew up, he cast around for something that could ground him amid the chaotic changes that his country was experiencing. Returning to the Gothic tradition that had long fascinated him architecturally, he became convinced that a person’s beliefs and behaviors are shaped by the built environment, and that traditions served as an anchor, not a shackle. The Reformation had, he held, not only unmoored contemporary Britons from their collective past but led directly to revolutionary and social upheavals. If Britain could re-forge the links to that old tradition, it might be possible to switch gravity back on.

Pugin’s early training as a draftsman in his father’s firm prepared him perfectly for a design career. At fifteen years old he was handling commissions for designs for the goldsmiths Rundell and Bridge, and for furniture at Windsor Castle. Within five years Pugin was designing theater sets for the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden. This was his first foray into large-scale work, and he learned valuable lessons on how to design for dramatic impact. In 1834 he converted to Catholicism—a risky move, given the long-established antipathy in Britain toward the faith of Rome—and gained access to a new set of patrons. For instance, John Talbot, sixteenth earl of Shrewsbury, had him design alterations and additions to his residence, Alton Towers, which soon led to many more commissions. Around the same time, Pugin built a country seat, a modest Gothic revival house he named St. Marie’s Grange.

In 1836 Pugin published his treatise Contrasts, which espoused his aesthetic theory and argued for the revival of the medieval Gothic style in addition to “a return to the faith and the social structures of the Middle Ages.” Living in a Gothic house, surrounded by Gothic material culture, would, he believed, lead one to better and holier actions.

In the Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851, a pavilion called the Royal Court, decorated by Pugin with medieval-looking artifacts, caused a sensation at the very heart of the avowedly “modern” showcase. Pugin used the opportunity to market a line of Gothic-revival objects, made more affordable by Victorian technological advances, in a non-ecclesiastical context. By selling people on a consciously Gothic lifestyle and mode of expression, he hoped to usher in the more pious age he’d sought for two decades.

Still committed to traditional craft, Pugin employed new technology to speed up production, but stopped short of entirely mechanizing it. This was key to matching the superb quality of the original Gothic pieces against which both Pugin and John Hardman, his metalworker and right-hand man, measured their own work.

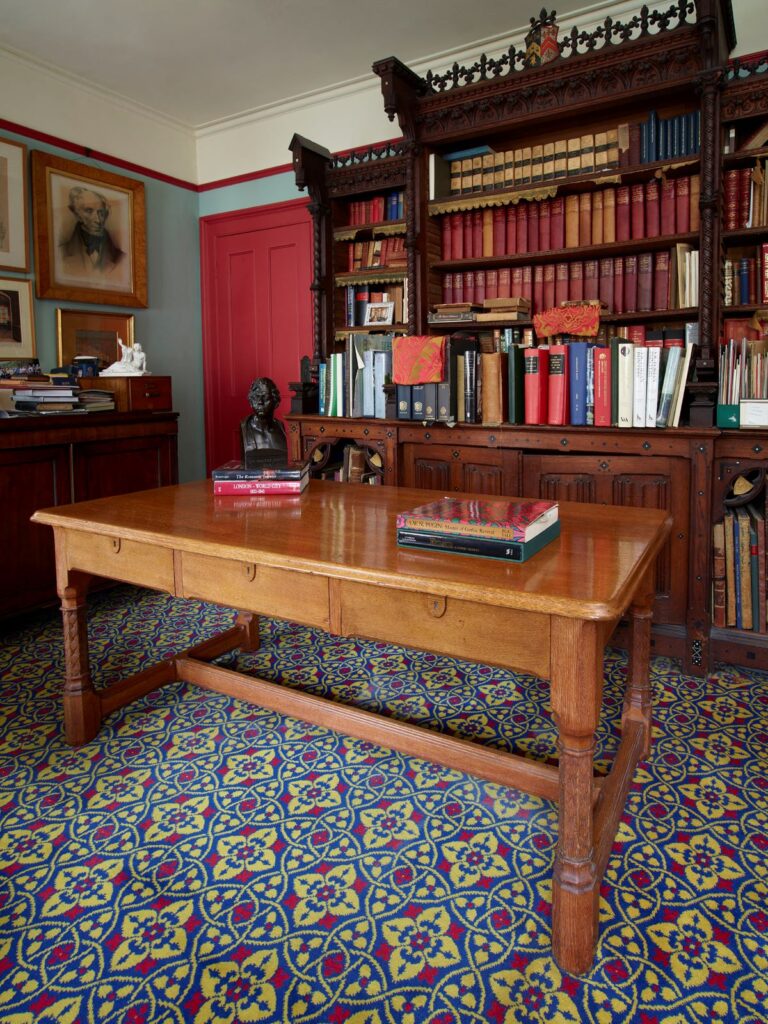

For Pugin, honesty in material and process were critical and interrelated. The direct carving method used by medieval craftsmen made decorative elements appear natural, as if occurring by the will of the stone itself. This practice can be seen in the wonderful simplicity of the drawing table of Pugin’s design that was shown by H. Blairman and Sons of London at the 2024 Winter Show in New York. The piece was Pugin’s own, which accounts for the table’s low height—Pugin was only 5 feet, 2 inches tall, and decorative arts scholar Clive Wainwright surmised that he stood at it to draw.

The table is not minimalist in the manner of our contemporary Scandi-style. Rather it is forthright in the expression of its purpose.Embellishments are executed without excessive affectation. A similar spirit can be found in the oak writing table with iron pulls Pugin designed for the Convent of Our Lady of Mercy (now Sisters of Mercy), Handsworth, Birmingham. There is a quiet confidence in the lines and curves of the piece, leaving one feeling that, although there is much about it that is decorative, none of it is extraneous. It exemplifies how familiar Pugin was with bona fide Gothic originals, as the same type of table appears frequently in illuminated manuscripts and would feel at home among pieces built for Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis in the twelfth century.

Pugin was one of the first to design in a Gothic style that actually drew on Gothic originals, a point of pride that he returned to in critiques of his predecessors and his contemporaries. In The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture, published in 1841, he lampooned undisciplined pastiches of Gothic style: “We find diminutive flying buttresses about an armchair, everything is crocketed with angular projections, innumerable mitres, sharp ornaments, and turreted extremities. A man who remains any length of time in a modern Gothic room, and escapes without being wounded by some of its minutiae, may consider himself extremely fortunate.”

Such acerbic comments infuriated many of his less competent contemporaries. The earlier Georgian Gothic was so much more Georgian than Gothic that, once you notice it, the historical inaccuracy becomes glaring. Pugin does not spare himself from criticism, either, spending a good deal of time pointing out the follies of his own early efforts. His 1827 design for the dining room sideboard and canopy in George IV’s private apartments at Windsor Castle, now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, is garishly encrusted with as many Gothic-esque elements as would fit, to Pugin’s future embarrassment. Pieces from his later career demonstrate the way he slowly developed his “true principles” of Gothic revival, emphasizing structural honesty. By the end of his life he’d found the perfect balance, and even in relatively elaborate designs such as the dining room chair made about 1847 for the Speaker’s House, Palace of Westminster, the decorations manage to harmonize with the structure of the seat. It does not require a mass of superfluous ornament to attest to its Gothic character. This simplicity and straightforwardness are what made Pugin’s work so influential to later designers. His ideas proved an inspiration to the arts and crafts of William Morris and William Price, and to the modernism of the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier.

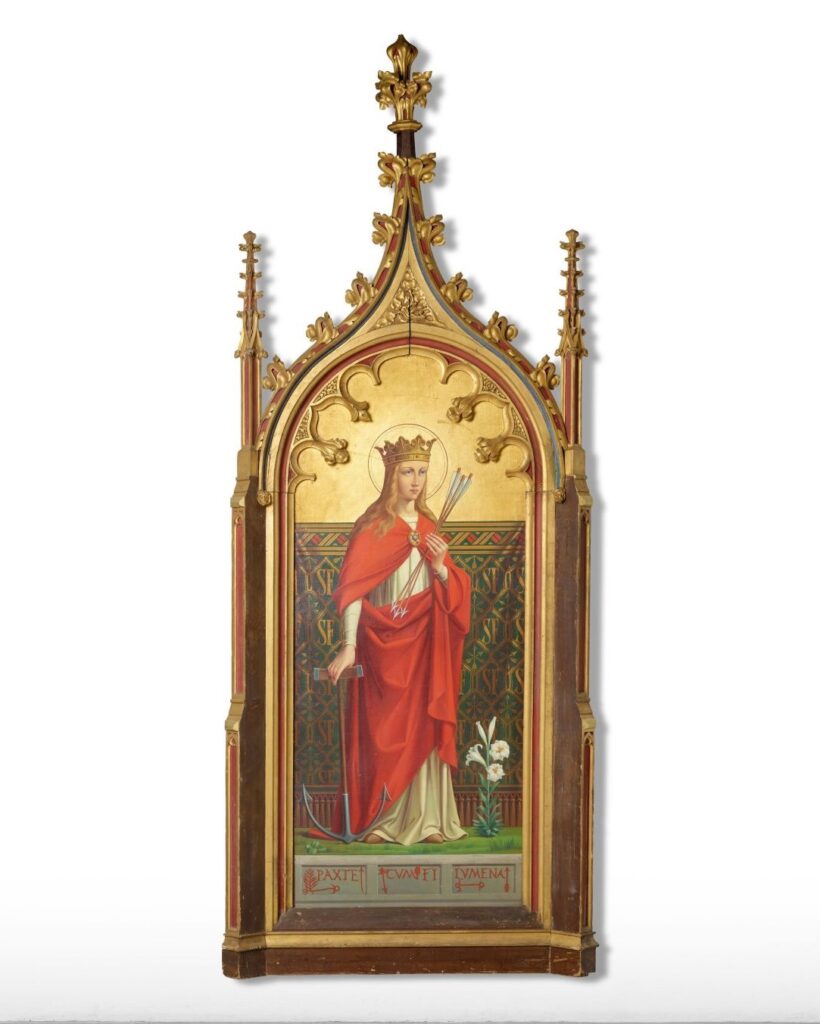

When a piece designed by Pugin comes on the market, his fame pushes the price up. While a chair or table “in the style of Pugin” can quite easily be found for $100 to $500, a center table attributed to Pugin sold at Bonham’s London in 2013 for £5,000. In 2023 a Pugin-designed painted panel depicting St. Philomena sold for $6,400 at Bonhams, and at Bamfords auction in Derby the same year a Pugin chandelier for St. Giles Roman Catholic Church in Cheadle went for £12,500, double the low-range estimate.

Shortly before dying, purportedly from overwork, at the age of forty, Pugin reflected on his career with disappointment. “I have passed my life in thinking of fine things, studying fine things, designing fine things, and realizing very poor ones.” Perhaps the ideal was unattainable, but as he wrote to Hardman in about 1851, “my writings, much more than what I have been able to do, have revolutionized the taste of England.” About this Pugin was entirely correct, part of why he remains among the most important designers and thinkers of the nineteenth century.