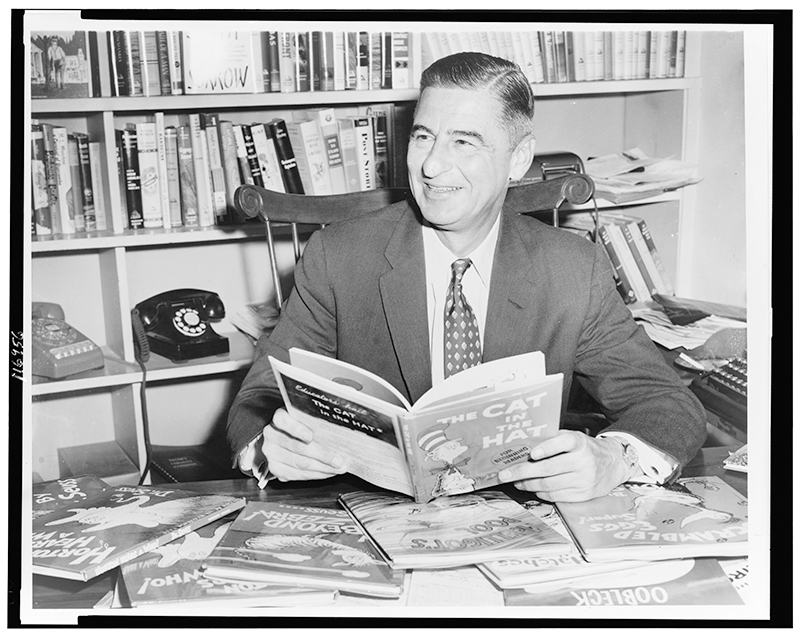

If Dr. Seuss did not exist, we would have a hard time inventing him, since we would have a hard time even imagining him. For the good doctor—who, of course, was never really a doctor of anything—seemed to emerge, a glorious aberration, out of nowhere. True, it is possible to find the roots of his work in the early twentieth-century funny pages, in the humorists of the then nascent New Yorker magazine, even in Dada and surrealism, which created a context and receptivity for his transcendent nonsense. But none of those elements, alone or in combination, accounts for Theodor Seuss Geisel’s art or for the mystic way in which, several generations on, it has almost become a self-evident extension of our shared universe.

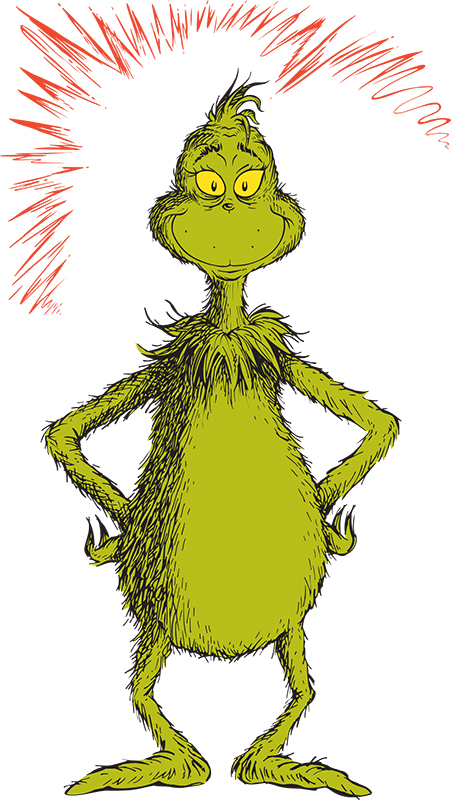

The Grinch from How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, 1957. Courtesy Random House Children’s Books.

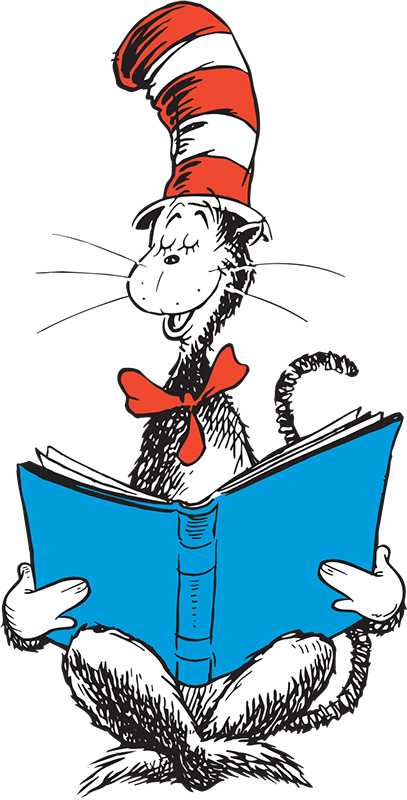

The cat from The Cat in the Hat, 1957. Courtesy Random House Children’s Books.

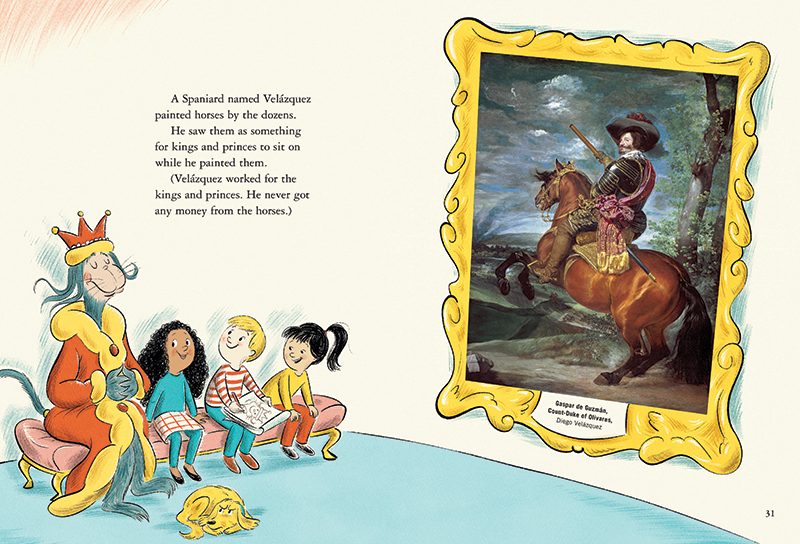

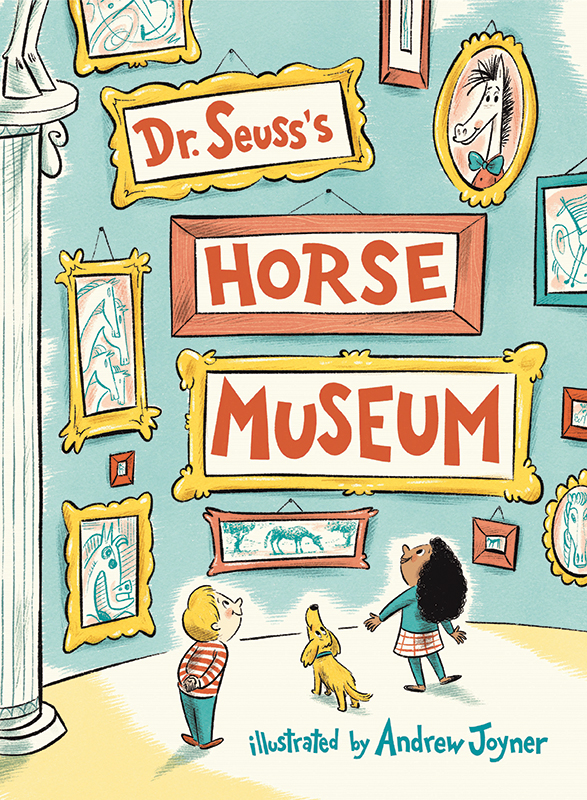

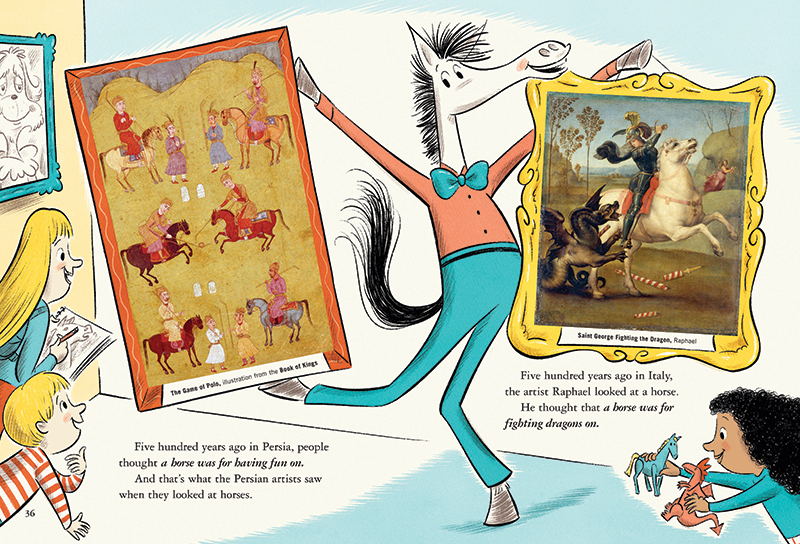

Nearly thirty years after he died in 1991 at the age of eighty-seven, Dr. Seuss remains as admired as ever. In addition to being the inspiration for the well-received Seussical the Musical, he is more prolific in death, perhaps, than he was even in life. With greater enthusiasm than prudence, publishers have rifled through his posthumous effects for any scrap of rhyme or any sequence of images that could be turned into a saleable book. A good example of this is the newly published Dr. Seuss’s Horse Museum. It is indeed based on an idea he had for a book, as well as on the script for a now lost television program, in which he initiated children into the world of visual culture. The original germ of the idea, which survives in the new publication, is to insert reproductions of famous images of horses by Velázquez, Picasso, and others into a frame and context conceived by Dr. Seuss. “Five hundred years ago in Italy,” the author informs us beside a famous depiction of Saint George, Raphael “thought that a horse was for fighting dragons on.” Several pages later, we are informed that “abstract art can have a subject—but it doesn’t NEED one!” and here a horse holds up, for the inspection of a boy and his dog, Jacob Lawrence’s The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture #34 and Wassily Kandinsky’s Lyrical.

The result is a book so earnest and well-intentioned, so eager to inform without offending, that one wishes one could speak more highly of it. Only a few rough sketches were executed by Geisel himself, and so the published illustrations and much of the text have been created by the Australian Andrew Joyner in a vaguely Seussian vein. Joyner’s serviceable images were composed on an iPad—as he explains in a postscript—and I am afraid that it shows: gone is that indefinable spark of genius, that sap that flows through each line, that perfection in imperfection that defines the graphic brilliance of Dr. Seuss.

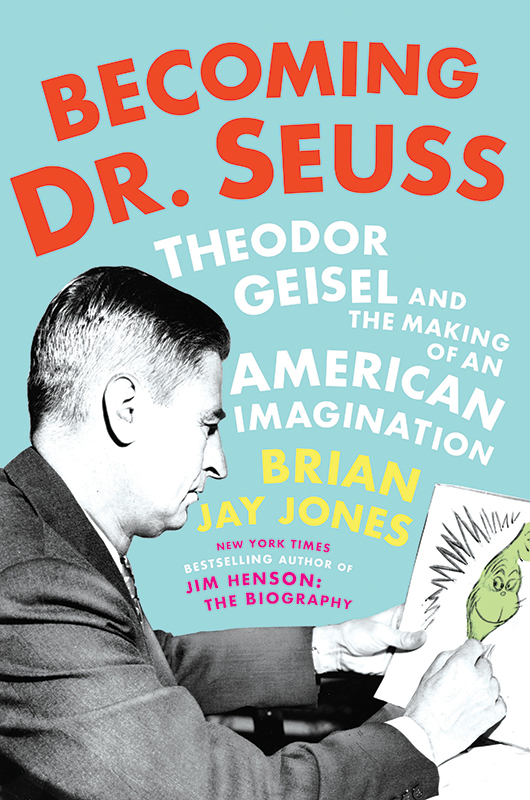

Becoming Dr. Seuss: Theodor Geisel and the Making of an American Imagination by Brian Jay Jones (New York: Dutton, 2019). 483 pp., color and b/w illus.

Dr. Seuss’s Horse Museum by Dr. Seuss, illustrated by Andrew Joyner (New York: Random House, 2019). 80 pp., color illus.

At the same time, Dr. Seuss has been the subject of several biographies, of which the newest is Brian Jay Jones’s Becoming Dr. Seuss: Theodor Geisel and the Making of an American Imagination. Although the author claims no access to any correspondence or archival material that was not available to earlier biographers, he dutifully and engagingly gives us the facts of Geisel’s life and career—from his relatively privileged childhood in Springfield, Massachusetts, to his studies at Dartmouth and Oxford, and his highly lucrative work in advertising: before writing a single book, he became rich with the immortal catchphrase “Quick Henry! The Flit!” for a bug repellent of that name. We learn of the fortuities that attended the publication in 1937 of his first children’s book, And to Think that I Saw It on Mulberry Street, after it had been rejected by numerous publishers, to his eventual creation of nearly sixty works with editor Bennett Cerf of Random House. But the title of Jones’s biography, that business about the “Making of an American Imagination,” promises more than its author cares to deliver. Jones, in short, does not seem especially interested in defining what makes Dr. Seuss the cultural icon that he is, or in illuminating the genesis, or specialness of Geisel’s art.

It seems fitting that this master of children’s literature should have remained, at least in Jones’s telling, an overgrown man-child to the end of his days. And it is doubtful whether Wordsworth’s great line—”The Child is father of the Man”—could ever be applied more accurately to anyone else. It takes absolutely no effort to find the roots of Theodor Geisel, that wealthy and successful adult, in the lazy practical joker and class clown from Springfield, who, even at Dartmouth and Oxford, by his own admission learned absolutely nothing.

But the one element of childhood that inspired Dr. Seuss more than anything was a kind of animism whereby every living creature and every object, from a teapot to a roller skate, inhabits a common and sympathetic universe. Each of these created things participates in a world of joys and privations, which—in spite of all the phoniness and pomposity that Dr. Seuss habitually skewers—is, at least in potential, a happy place. In the snow-covered houses that the Grinch invades as he seeks to abrogate and annul Christmas itself—in the model boats and Yule logs and tilting Christmas trees that he carries off, in the tiny mouse and two-year-old child he encounters along the way—there is a seamless and unshakeable fellowship of feeling.

The guiding ethos of Dr. Seuss’s universe is that of Roosevelt’s near-contemporaneous New Deal, where, in the end, everyone is protected, and the powerful—even the Grinch stealing Christmas—is ultimately redeemed in the name of communitarianism. This sentiment is conveyed graphically in the hatchings of the heavily inked lines, no less than in the bold colors that dominate each page, with all that they owe to such earlier cartoonists as Winsor McCay and Rube Goldberg. Everything is slightly off kilter in Dr. Seuss’s universe: no symmetry or forced order informs his landscapes or his interiors. Floors and walls curve at will, just as the laws of physics are held in perilous suspension during the virtuosic juggling of the Cat in the Hat.

Out of such formal and affective convictions Dr. Seuss fashioned an alternate universe, a fallen and imperfect world awash in human frailty and ultimately redeemed by that frailty. There is beauty everywhere in his world, but it is not the beauty of refinement or perfection, but of fellowship and human sentiment. It would be foolhardy to assess this achievement within the ordinary terms of artistic formalism, even though the perfect matching of Dr. Seuss’s means to his ends compels our admiration. Beyond that, however, very few artists, in the broadest sense of that term, have received the gift that Dr. Seuss possessed in a supreme degree: to be an inventor of worlds, to body forth alternative universes into which readers of all ages can retreat and find therein peace and beauty and shelter from an often pernicious present.