Fig. 1. Young Woman with Peonies by Frédéric Bazille (1841–1870), 1870. Signed and dated “F.Bazille./ 1870.” at upper right. Oil on canvas, 23 5/8 by 29 5/8 inches. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon.

The photograph, by Albert Brichaut, depicts a Parisian brothel at 2 rue de Londres in the year 1900. It would seem to be one of the better brothels of the capital, elegantly appointed to welcome men of standing, and decorated with the sort of velvet upholstery, fringed curtains, and ormolu candelabras that might suggest to its exalted clientele that they had just stepped into their own hôtels particuliers. Four women present themselves to the camera in a state of evident availability. Three of them, as pale as lilies, are dressed in white linens. But the fourth is a dark-skinned woman of African descent who is dressed—to the extent to which one can judge from the black-and-white image—in a shimmering blue satin robe. What is so striking about her is that she seems almost like a time traveler: her hair, posture, and sleeveless dress make perfect sense in our world, but little sense in the context of the Belle Époque.

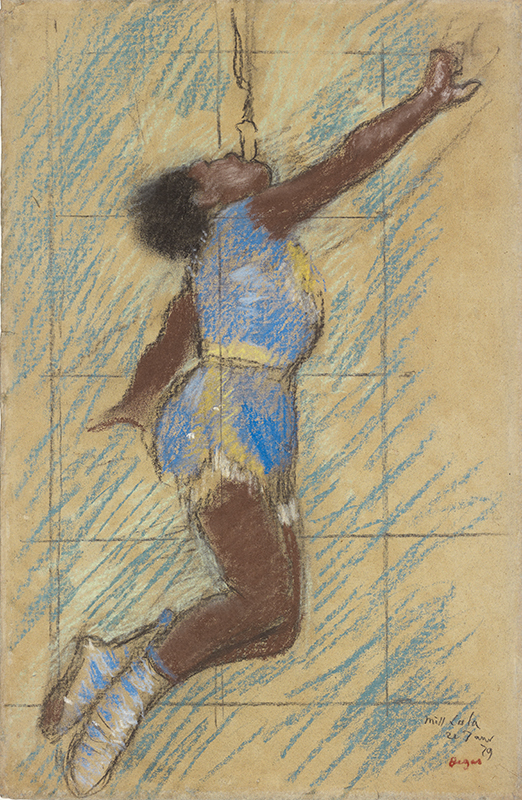

Fig. 2. Miss Lala at the Cirque Fernando by Edgar Degas (1834–1917), 1879. Inscribed “Mill [sic] Lala/ 21 Janv/ 79/ Degas” at lower right. Pastel on paper, 18 1/4 by 11 3/4 inches. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California.

Fig. 3. La négresse (Portrait of Laure) by Édouard Manet (1832–1883), 1863. Oil on canvas, 24 by 19 3/4 inches. Giovanni and Marella Agnelli Picture Gallery, Turin, Italy; photograph by Andrea Guerman, © Pinacoteca Giovanni e Marella Agnelli.

Black men, far more than black women, have appeared in Western art since antiquity, and they were a fairly regular presence, especially north of the Rhine, in old master depictions of the Three Magi and Saint Maurice. Starting in the seventeenth century, however, in Holland and elsewhere, they began to appear in the supporting role of manservants, and on several memorable occasions they sat for their own portraits: in Velázquez’s depiction of Juan de Pareja at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Rubens’s studies of the head of a black man, in the Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts in Brussels.

Fig. 4. Olympia by Manet, 1863. Signed and dated “ėd. Manet, 1863” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 51 1/8 by 74 3/4 inches. Musée d’Orsay, Paris; © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/ Patrice Schmidt.

But at the beginning of the nineteenth century, a pivotal change occurred in the depiction of black subjects, especially, and crucially, black women. In an age in which the fledgling disciplines of ethnology and anthropology were introducing Europeans to new worlds, black Africans were no longer simply odd aberrations from whiteness, but subjects of cultural interest in their own right. At the same time, with the promulgation of the droits de l’homme and the emancipation of slaves throughout the colonies of France and England, black Africans assumed—from the perspective of the West—full membership in the family of man.

Yet it was not black men so much as black women, who, for most of the nineteenth century, represented the point of contact with white painters. The interest that romantic artists like Géricault and Delacroix had in the black male figure was not generally shared by realist painters and impressionists. In black women, however, the erotic and exotic converged. Charles Baudelaire, whose black mistress and muse, Jeanne Duval, is the subject of a Manet portrait in the Wallach show (Fig. 7), expressed this sentiment in his poem “À une Malabaraise” (To a Woman of Malabar):

Ta hanche

Est large à faire envie à la plus belle blanche . . . .

…………………………………………………..

Tes grands yeux de velours sont plus noirs que ta chair.

Aux pays chauds et bleus où ton Dieu t’a fait naître…

Your broad haunch

would inspire envy in the most beautiful white woman . . . .

………………………………………………….

Your large velvet eyes are blacker than your flesh.

In those hot and blue lands where your god gave you birth…

As early as 1800, Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait d’une négresse had depicted a young woman in a white headscarf against a light backdrop, her pale robe falling away to reveal a bared breast. Half a century later, the academic sculptor Charles Cordier invested that eroticism with a startling ethnographic realism in Venus Africaine, a portrait bust of a young woman. But it was the impressionists most of all who heralded a shift in the depiction of black women.

Fig. 5. Female Model by Thomas Eakins (1844– 1916), c. 1867–1869. Oil on canvas, 23 by 19 3/4 inches. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Mildred Anna Williams collection.

Through a curious fortuity, these two marginal subsets of nineteenth-century French society, avantgarde painters and the growing African and Antillais populations, came to inhabit the same newly developed neighborhoods near the periphery of Paris: the Quartier de l’Europe in the 8th arrondissement and the Plaine Monceau in the 17th. The interest the impressionists found in the black female body was thus tied to the steady growth in the number of black Parisians in their vicinity, after the abolition of slavery throughout the French colonies. In what is perhaps his best-known work, Olympia of 1863 (Fig. 4), Manet appears to depict a courtesan, whose strikingly white figure almost dissolves into the whiteness of the sheets on which she lies. Far less conspicuous is her black serving woman: as she delivers a bouquet of flowers from one of Olympia’s admirers, she, too, almost disappears into the dark wooden tones behind her. This painting is not in the Wallach Gallery, but the show includes a nearly contemporaneous unfinished portrait of the same model, Laure, whom the exhibition catalogue quotes Manet describing as a “très belle négresse”(Fig. 3). In a similar spirit, one of Manet’s most gifted disciples, Frédéric Bazille, painted a sensitive portrait of another black woman bearing flowers, Young Woman with Peonies (Fig. 1). Here, the sitter stretches out her hand to offer a flower to the viewer, into whose eyes she seems to look directly. A rare American painting that partakes of this realism is Thomas Eakins’s 1869 Female Model, included in the present show, which depicts a young black woman, naked except for the bandanna on her head (Fig. 5).

Fig. 6. Why born a slave! or La négresse: Pourquoi! Naître esclave! by the workshop of Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827–1875), 1872. Inscribed “pourquoi!naitre esclave!” on front of base and “j.b. carpeaux 1872” on proper left side of base. Cast terracotta, height 24 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of James S. Deely in memory of Patricia Johnson Deely.

In such images, Manet and Bazille appear to be responding to Baudelaire’s injunction to contemporary artists to paint modern life, an injunction that in practice resulted in a somewhat dispassionate record of daily life in the most modern city in the world. But as we saw in Baudelaire’s poem “À une Malabaraise,” the erotic, symbolist resonance of the black woman is every bit as important as the almost journalistic view that Manet and Bazille adopted. It is worth noting, however, that not all the impressionists shared Manet and Bazille’s interest in the black female figure. Renoir, despite the thousands of female forms he painted, drew, and sculpted in the course of his long career, rarely, if ever, depicted a black woman (or man). Degas depicted the black aerialist Miss La La of the Cirque Fernando (see Fig. 2) in 1879, but never seems to have returned to the theme. The postimpressionists and symbolists, as well, exhibited at best a sporadic interest in the subject.

Fig. 7. Baudelaire’s Mistress (Portrait of Jeanne Duval) by Manet, 1862. Signed “Manet” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 35 1/2 by 44 ó inches. Museum of Fine Arts (Szépművészeti Múzeum), Budapest; photograph by Csanád Szesztay, © The Museum of Fine Arts Budapest/ Scala/Art Resource, New York.

Rather, it was the Fauvists at the beginning of the twentieth century who reintroduced the theme and placed it in the mainstream of Western art, through such classic works as Matisse’s 1908 sculpture Deux négresses and his painting La petite Mulâtresse (The Young Mulatto Woman) of four years later. In a series of lithographs, including Haitian Woman with Hoop Earrings (1945) in the present show, Matisse records with nothing more than a few wiry lines the women of the Antilles, as he reasserts the exotic rather than the journalistic part of Baudelaire’s influence.

Fig. 8. Dame à la robe blanche (Woman in white) by Henri Matisse (1869– 1954), 1946. Signed and dated “H Matisse/ 46” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 35 5/8 by 23 . inches. Des Moines Art Center, Iowa, gift of John and Elizabeth Bates Cowles, © 2018 Succession H. Matisse/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; photograph by Rich Sanders.

The next phase in Western artists’ engagement with the black female subject occurs in America, among black artists, male and female, who were associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Even as they invoke certain formal tropes inspired by Fauvism, the paintings of Charles Alston, Norman Lewis, and William H. Johnson obviously avoid any sense of Matisse’s exoticism: they engage their subjects all the same with a commitment that was alien to the journalistic aloofness of Manet and Bazille. This engagement is even more pronounced in Laura Wheeler Waring’s touching 1927 portrait of Anna Washington Derry, an elderly black woman who sits with arms folded across her chest.

Fig. 9. Portrait of a Woman in a Blue Turban by Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), c. 1827. Signed “EugDelacroix.” at center right. Oil on canvas, 23 3/4 by 19 3/8 inches. Dallas Museum of Art, the Eugene and Margaret McDermott Art Fund, in honor of Patricia McBride.

In the past generation, black women artists have revisited the theme of the black female figure, this time with a palpably political angle. Faith Ringgold’s chromatically audacious painting Matisse’s Model (1991) reimagines the circumstances of the French master’s depiction of black women, as does Ellen Gallagher’s photographic collage Odalisque (Self-Portrait with Freud as Matisse) of 2013, in which the American artist reenacts a famous photograph of Matisse at work. At this point, where the Wallach exhibition ends, one feels as though the circle had closed, with the outsider, incarnated in the black female, having come to occupy the vibrant center of contemporary artistic practice in the West.

Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today is on view at Columbia University’s Wallach Art Gallery until February 10.