Many readers of this magazine will recall with admiration the interpretive work of curator Morrison Heckscher in the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. For almost fifty years he enabled the meticulous reexamination of otherwise long-accepted conclusions about the origins of American decorative traditions. Perhaps this is why, among conservators and craftsmen specializing in early American furniture, Heckscher’s word is gospel.

Indeed, in the New Hampshire workshop of master cabinetmaker Allan (Al) Breed, the onebook that sits atop the worktable, like a Bible, is Heckscher’s American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Late Colonial Period: The Queen Anne and Chippendale Styles. “If you only have one book, this is it,” Breed advises others in the trade. Breed, who has been crafting fine reproductions of early American furniture since the late 1970s, owes a debt to Heckscher and rare curators like him. “When he was curator of American decorative arts at the Met,” Breed recalls, “he took pieces right off the wall for me to measure.” Breed’s work would be impossible without access to reference pieces, but with strict access regulations at museums, this is not always possible. It is curators like Heckscher who make it so.

Breed’s career began with another such museum professional when, in 1974, he appeared on the doorstep of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, asking for a job. He was a young man with an affinity for antiques markets and was hooked on the idea of restoring furniture. “They said no,” he recalls cheekily. “But, ‘you can volunteer.’ So I did.” Breed apprenticed for several months with the MFA’s restorer, Italian-trained cabinetmaker Vincent Cerbone. “It was from Vinnie that I learned the rudiments of hide glue, carving theory, and furniture construction while we took apart and reassembled pieces from the museum’s collection.” When Cerbone passed away, Breed purchased many of his tools, especially a sophisticated collection of wood- carving tools. Two years later, he and a group of fellow students from the North Bennet Street trade school in Boston opened their own shop in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

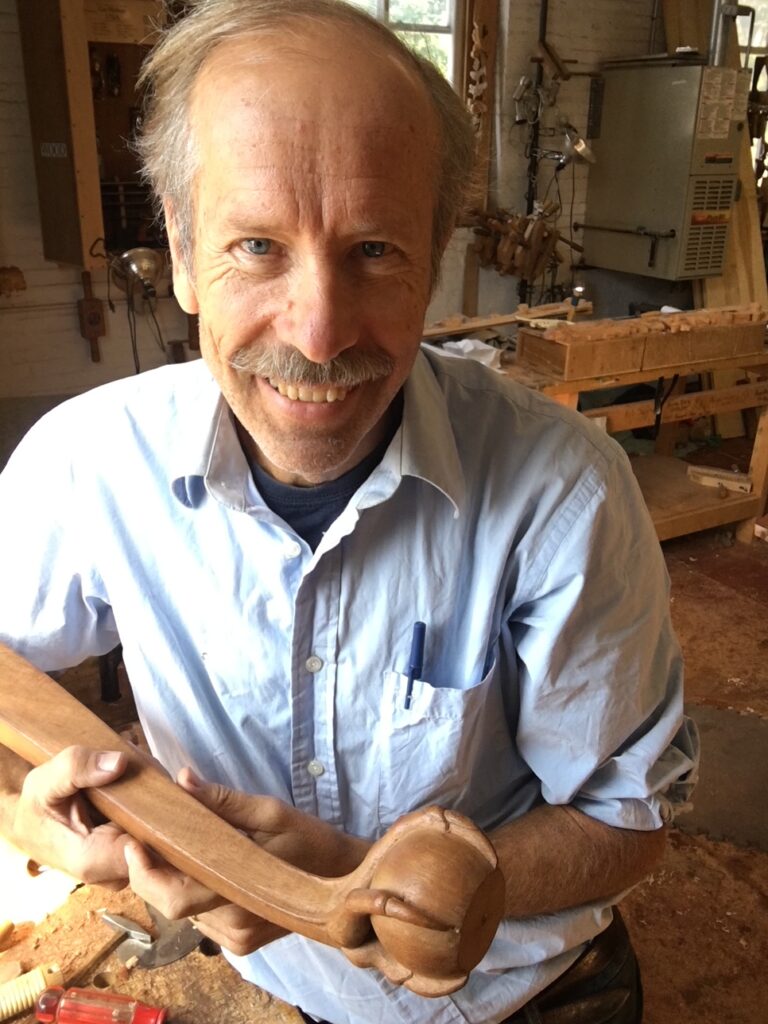

The years since have taken Breed all over the country in pursuit of more challenging work. He has made reproductions for museums and private collectors, doing restoration work in addition—everything from claw-and-ball feet to clock cases to elaborate rococo mirrors. “I love challenging work,” he says, pointing to a Philadelphia rococo mirror he is currently carving (Figs 1a–c.). “It humbles you.”

Breed’s work feels like a lost art. “All this stuff can be made by machines,” he says. “But there are people who still prefer something made by a person.” With this philosophy in mind, he is passing on his craft. He has spent much of his career teaching others, whether at the Sotheby’s Institute of Art, or in his studio. He typically hosts around six classes per year, for a week or even just a weekend, teaching skills like carving and veneering, giving students the opportunity that the MFA gave him.

Fig. 3. Photo-composite plan for a Philadelphia rococo-style looking glass. Photograph by Michael Turner.

Fig. 4. Looking-glass frame by Breed, 2013, based on a c. 1769–1775 Philadelphia example in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Painted white pine; height 48, width 26 inches. Truslow photograph.

Fig. 5. Template by Breed for a cartouche to decorate the mantelpiece of a house in New Hampshire, c. 2013. White pine, height 48, width 26 inches. Bilotta photograph.

Don’t be fooled. It’s complicated work that takes years to master. “When you’re looking at a piece, you have to kind of figure out what process was used and what [the maker] did first.” It requires cunning investigation and a strong understanding of historical methods of furniture construction. Tacked onto a bulletin board in a corner of his studio is a curious X-ray of a chair back (Fig. 2). It was part of Breed’s early furniture restoration detective work, back in 1977. It’s the first chair he ever reproduced for a customer. “I was curious what the joint looked like,” Breed says. So, he handed the country Chippendale chair of about 1790 over to a radiologist friend who took it to work and X-rayed it. “It’s pretty poorly made,” he chuckles. “Look at the gap in the mortise-and-tenon joint.”

To do this work, Breed notes, you also have to be good at drawing. In practice, you outline shapes and motifs in pencil directly on the wood, but then you cut them off. So, if you need to go back to the original template, you have to be able to draw it again. Breed and his son, who worked with him until five years ago, have also used photography in the studio, to make full-size composites that are then used to make a pattern. On a table in the center of the studio is the composite for the rococo mirror he is currently carving (Fig. 3). He is making two of them for a client. They are based on a white pine Philadelphia looking glass of about 1775. This is the second time in his career he’s undertaken a reproduction of this exact piece. Previously, in 2013, he completed a reproduction that, to the specifications of his client, was painted in gleaming white (Fig. 4). A photograph of the finished product hangs on a clothesline over his workbench.

On a table beside the workbench is a display piece that catches my eye. It is an elaborate carved shell motif, made as a template for a mantelpiece in a home in New Hampshire (Fig. 5). Breed worked in collaboration with an architect to design the piece, which was then sent to Italy in 2013 to be reproduced in marble. Set beside the shell cartouche is a section of a gilded frame, a copy of an eighteenth-century John Welch frame made for a John Singleton Copley portrait in the MFA, Boston. Breed produced another copy for an art collector in 2015. Across the expansive studio stands another workbench, where I spot some of the most elegant veneering I’ve ever seen—made for a Federal-style chest of drawers (Figs. 8, 8a). The original is from about 1800 and was made in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, by the prosperous cabinetmaker Langley Boardman.

I am in awe to be this close to so many precise reproductions of early American furniture. It is as close as I might get any time soon to the real thing. But, Breed’s studio is not just a gallery of historic cabinetry styles. It is a working shop, floor strewn with wood shavings, that familiar smell wafting across the space. And, it’s full of tools, each with a purpose. Breed maintains an entire wall of hand planes of different sizes and a cabinet of carving tools in different shapes and dimensions (Fig. 10). They remind me that everything in his studio was made without machinery.

The studio is set high up above the Salmon Falls River, in early nineteenth-century mill buildings in Rollinsford, New Hampshire, that have been converted into artist studios (Fig. 9). Periodically, a train rolls by mere feet from the window. Breed has been in this space since 2003. He is surrounded by other craftspeople, young and old, who work from their spacious studios. However, he is most certainly the only one in the entire complex who is actively producing “eighteenth-century” furniture. It brings to mind the question of whether this work, this style of furniture in general, is going out of fashion.

“I think the trade and the antique furniture market will have a generation before they come back,” Breed says. “My kids don’t want a house full of brown furniture.” But, it wasn’t long ago that Scandinavian-inspired blocky modern furniture was in the same position. These things come and go. In the meantime, Breed is as busy as ever, perhaps an indication that the brown furniture market is not as dead as it is perceived to be. Breed anticipates that it will only get busier, which is why he continues to pass on his skills to eager students. His career demonstrates how museums and craftspeople can, and do, collaborate to tell the history of American furniture design. It is a humbling reminder of how crucial both are to sustaining collections of historic American furniture for the future.