The Magazine ANTIQUES | September 2008

Spotting a few plates from the Vienna porcelain manufactory in an antiques shop in the Camden Passage, London, in 1994 was the beginning of it all. Today, Richard Baron Cohen’s Twinight Collection is the largest assemblage in private hands of early nineteenth-century porcelain from the royal manufactories at Sèvres, Berlin, and Vienna, rivaled only, perhaps, by museum collections like that of the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg. This month an exhibition of a fine selection from this splendid collection opens at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, after traveling for a year in Europe.

Fig. 1. Pair of vases with cameo portraits painted by Jean Marie Degault (1765–1818), Sèvres porcelain manufactory, France, 1814. Signed “JMDeGault” in the cameo medallions. Porcelain with gilt-bronze handles, height of each 21 5⁄8 inches.

What made a successful businessman from New York fall in love with this fragile material, the details of which are often so minutely painted as to be hardly visible except on the closest examination? Cohen describes his passion with one word, “precision.” He is fascinated by the refined painting achieved by the major continental porcelain manufac-tories in a time of transition from highly developed artistry to industrial technology. But then, he also likes to commune with his collection. “I believe that objects have a soul,” he says. Playing with words, he coined the name Twinight for both his house and his collection while enjoying the delicate pink of twilight, his favorite time of day, on a beautiful beach near his house. From the time he wakes each morning to the sight of colorful botanical plates of 1823 to 1832 from Berlin’s Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur (Royal Porcelain Manufactory; KPM), until darkness descends, he takes great joy in the porcelains throughout his house.

Fig. 2. Plate from the Arts Industriels service (beer brewing), painted by Jean Charles Develly (1785–1849), Sèvres, 1827. Initialed “CD” in the image. Porcelain, diameter 9 1⁄8 inches.

Many of the objects in Cohen’s collection have important provenances. Numerous examples bear likenesses of emperors, kings, queens, princesses, and generals that identify them as royal gifts, and their stately splendor is often enhanced by rich neoclassical ornament in raised, incised, or polished gold. But there are also more subtle aspects to the porcelain of this period. Botanical flower painting, for example, is one of the most difficult skills for a porcelain painter to acquire. It requires a deep knowledge of nature and a mastery of color, for the changing “moods” of enamels when being fired have always presented porcelain painters with enormous challenges. In addition, the art of botanically correct yet decorative porcelain painting requires a large palette of colors, and this did not develop until about 1800. The expanding palette developed in Vienna—including the famous deep blue, Leither-Blau, named after the factory´s chemist Joseph Leithner (active 1770–1829), orange, and a bright chrome green—was greatly admired by the other important manufactories in Europe. Chemists and artists began to cooperate with one another and factory directors exchanged samples and recipes, all of this while Europe was dominated by the armies of Napoleon Bonaparte. Indeed, additional stimulus for creativity occurred when the Congress of Vienna met from 1814 to 1815 to lay out a new order on the map of Europe. “Nationality” received a new meaning, and local landscapes and depictions of the latest architectural achievements made perfect subjects for garnitures of vases or breakfast services ordered as diplomatic gifts by and for the many royal courts involved in the negotiations. throughout his house.

Fig. 3. Richard Baron Cohen with a porcelain teapot from the Egyptian déjeuner service made by Sèvres, 1810–1812. The teapot was given to Louise Antoinette Guéheneuc, duchesse de Montebello (1782–1856) by Napoleon I (r. 1804–1815). On the shelf are pieces from the Forestierservice by Sèvres, 1835–1845.

Many of the objects in Cohen’s collection have important provenances. Numerous examples bear likenesses of emperors, kings, queens, princesses, and generals that identify them as royal gifts, and their stately splendor is often enhanced by rich neoclassical ornament in raised, incised, or polished gold. But there are also more subtle aspects to the porcelain of this period. Botanical flower painting, for example, is one of the most difficult skills for a porcelain painter to acquire. It requires a deep knowledge of nature and a mastery of color, for the changing “moods” of enamels when being fired have always presented porcelain painters with enormous challenges. In addition, the art of botanically correct yet decorative porcelain painting requires a large palette of colors, and this did not develop until about 1800. The expanding palette developed in Vienna—including the famous deep blue, Leither-Blau, named after the factory´s chemist Joseph Leithner (active 1770–1829), orange, and a bright chrome green—was greatly admired by the other important manufactories in Europe. Chemists and artists began to cooperate with one another and factory directors exchanged samples and recipes, all of this while Europe was dominated by the armies of Napoleon Bonaparte. Indeed, additional stimulus for creativity occurred when the Congress of Vienna met from 1814 to 1815 to lay out a new order on the map of Europe. “Nationality” received a new meaning, and local landscapes and depictions of the latest architectural achievements made perfect subjects for garnitures of vases or breakfast services ordered as diplomatic gifts by and for the many royal courts involved in the negotiations.

Fig. 4. Plate with lilacs made by the Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur (Royal Porcelain Manufactory; KPM), Berlin, 1820. Porcelain, diameter 9 7⁄8 inches.

Apart from their serious historical background, Cohen’s porcelains offer great visual pleasure. In addition to their delicious colors and irresistible gilding, wit and surprise in the form of flower riddles, hidden figures, and amusing scenes enhance the almost monumental simplicity of the forms themselves.

Admiration of antiquity was a main impetus for the arts of this period, reflected not only in the shape of porcelain objects but also in their decoration. An example is the pair of slender amphora vases with fine gilt-bronze handles in Figure 1, painted with cameos of Augustus and Julius Caesar against an immaculate beau bleu (dark blue) ground. Napoleon ordered these vases from Sèvres for his residence in Rome in 1809, but before they were completed he had to give up Rome, and the vases remained on a shelf at Sèvres until 1825. At that time the new French king, Charles X (r. 1824–1830), presented them to the composer Gioachino Rossini (1792–1868) in appreciation for the opera Il viaggio a Reims, which he had composed for the coronation. Here the illusion of the vitreous quality of ancient cameos is captured perfectly. In other instances, objects were painted to imitate ancient Roman micromosaic decoration (see Figs. 5, 6), a technique invented at KPM following a fashion begun by Josephine (1763–1814), empress of France, and also taken up by the Prussian queen Louise (1776–1810), who ordered micromosaic jewelry from the Vatican workshops.

Fig. 5. Cup and saucer with trompe l’oeil micromosaic decoration and lapis lazuli ground, KPM, c. 1805. Porcelain; height of cup 2 5⁄8, diameter of saucer 5 5⁄8 inches.

The competition among the royal porcelain factories is especially evident in the vases they created. Cohen owns a pair of the second largest ones ever made at KPM (see Fig. 12). Produced to impress the visitors at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1855, they were painted by Hermann Looschen and Wilhelm Escher with biblical scenes after murals by Wilhelm von Kaulbach at the newly opened Neues Museum in Berlin. Eventually Frederick William IV (r. 1840–1861) of Prussia gave the vases to Friedrich I (1826–1907), grand duke of Baden, and Cohen purchased them from an estate of the house of Baden. How does one live in the company of such monumental vases? Or with a service given to a hero? “Great objects are like great people, you respect them,” says Cohen; as an example he had specially designed niches built in his house to hold the Baden vases.

Fig. 6. Plate with trompe l’oeil micromosaic decoration by Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm Maywald (1766–1842), KPM, c. 1803. Signed “Maywald” on the back. Porcelain, diameter 9 ¾ inches.

Cohen finds that one of the great pleasures of porcelain collecting is reuniting pieces that have been separated by history. To return a teapot or a tray to its original déjeuner service is wonderfully satisfying. Even separated couples find each other again with his help, as was the case with Frederick William III (r. 1797–1840) and Queen Louise, whose portraits on KPM porcelain plaques of 1815 were apart for 150 years, until Cohen discovered them, respectively, on the art markets in New York and London within a year of each other. “Such happy reunions do not happen too often among real people,” he remarks with a smile.

Fig. 7. Krater vase with flower-painting by Joseph Nigg (1782–1863), Vienna porcelain factory, c. 1828. Porcelain, height 13 ¼ inches.

Cohen has never bought art as an investment. It has always been love at first sight: “The moment you buy for investment reasons, you cease to be a collector and you become a speculator,” he observes. He has been known to fly across the Atlantic once a week if necessary in pursuit of coveted pieces. As a self-described “control freak,” he prefers to buy at auction himself, even though he dreads the uncertainty of the situation. His calm, compassionate, and highly sensitive personality is rare and impressive. When a small KPM plaque with a painting of the Charlottenhof Palace in Potsdam, a neoclassical jewel designed by Karl Friedrich Schinkel, came up at auction in 2005 and exceeded the budget of the Stiftung Preussische Schlösser und Garten (Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation; SPSG), Cohen spontaneously bought it for them. And he has continued to acquire for himself even while his collection is traveling. Most recently he purchased a large Sèvres vase with gilded dolphin handles, a chrome green ground, and an exquisite portrait of Louis Antoine d’Artois, duc d’Angoulême (1775–1844), the dauphin of France, a military officer, and the consort of Marie-Thérèse Charlotte (1778–1851), the only surviving child of Marie Antoinette (1755–1793). It was once a gift from Charles X to his grandson, Henri d’Artois, comte de Chambord (1820–1883).

Fig. 8. Plate, Vienna porcelain manufactory, c. 1791. Inscribed with the painter’s number “76” on the back. Porcelain with raised gold ornament and bronze luster ground, diameter 9 ½ inches.

As the current exhibition demonstrates, Cohen feels a strong obligation to share his collection. The idea of celebrating his fiftieth birthday with a European showing of some four hundred pieces from the twenty-five hundred he owns arose when he met Samuel Wittwer, the curator of ceramics at the SPSG in Berlin-Brandenburg. At first the show was scheduled to be seen only at the Charlottenburg Palace in Berlin, but soon after the enormous crates arrived in Europe, it seemed natural to present it in the other cities where the porcelain was “born.” Soon the Liechtenstein Museum in Vienna joined as a partner, followed by the Musée national de Céramique-Sèvres. The finale at the Metropolitan Museum (where some ninety-five pieces will be on view) seems like the perfect ending of a long story: “I often went to the Metropolitan Museum as a child,” Cohen recalls, “and I never anticipated having my collection exhibited there. This is the best thing that could have happened, finally my vindication. For many years, no one at home understood my passion for porcelain, but now it all makes sense.” As a happy continuation, he has now found a companion in his love of porcelain in his eldest son, Adam.

Fig. 9. Tray from the Art de la porcelaine service painted by Develly, Sèvres, 1816. Signed “C. Develly” and dated “1816” in the picture, and inscribed “le magasin de sèvres le 25 Juin 1816” on the picture frame. Porcelain, length 17 1⁄8 inches. The scene depicts the visit of Louis XVIII (r. 1814–1824) to the Sèvres salesroom on June 25, 1816.

While Cohen has not missed his porcelain while it has been traveling, he has found that visiting it in different exhibition venues is a great experience. Moreover, he enjoys the fresh perspective provided by its absence at home, although even without this part of his collection, his house is filled with porcelain and other beautiful objects. Since 1998, for example, his eye has been drawn to miniature portraits, his favorites being by the English miniaturist John Smart (see Fig. 11), whose accuracy and subtle style of painting on ivory speak to Cohen in a way similar to miniature painting on porcelain, which launched this new love.

Fig. 10. Breakfast service painted with views of the gardens of the Château de Saint Ouen, Sèvres, 1822. Porcelain, length of tray 17 ¼ inches. The service was given to Zoë Victoire Talon (1785–1852), comtesse du Cayla, by Louis XVIII.

In Cohen’s eyes one of the other responsibilities of being a collector is being a patron too. To this end he has commissioned the Royal Copenhagen porcelain manufactory to produce a large dinner service decorated by the Danish porcelain artist Jørgen Steensen with portraits of hundreds of different members of the species Hippopotamus amphibius, of which he is exceedingly fond. Sarah Louise Galbraith, Cohen’s former assistant, traveled the world to photograph these large, dangerous, but family-loving animals in all possible zoos on all continents for the service. The shapes of the pieces are taken from the famous Flora Danica service, first produced by Royal Copenhagen in the late eighteenth century and one of Cohen’s favorites. Indeed, he has also commissioned Royal Copenhagen to produce three thousand pieces of Flora Danica decorated after original drawings of plants, such as grasses, seaweeds, or fungi, that were not translated onto porcelain in the past. It will take six years to complete, and special exhibition space will be created for its display in Denmark.

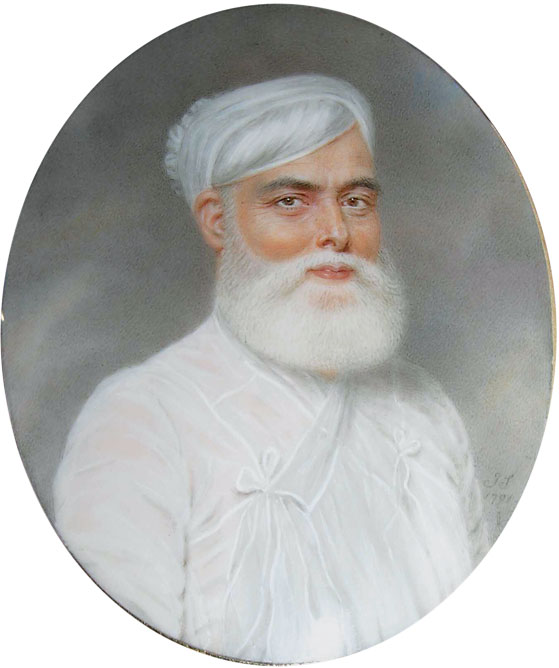

Fig. 11. Portrait of Muhammad Ali Khan, Umdat-al-Mulk Anwar al-Din (1717/18–1795), Nawab of Arcot,by John Smart (1741–1811), 1791. Initialed and dated “JS/1791” at right. Watercolor on ivory, 2 7⁄8 by 2 1/4 inches. Photograph by courtesy of the Twinight Collection.

A man with a twinkle in his eye, who has discovered great joy in porcelain, Richard Baron Cohen is a true collector—he follows in the tradition of his royal predecessors, who took both great risks and great pleasure in making their visions come true. His porcelain collection reveals not only the refinement of an era, but also the human interests, worries, and victories in a crucial time of European history.

Fig. 12. Vase, one of a pair, painted by Hermann Looschen (1807–1873) and Wilhelm Escher (1814–1871) with scenes from the Old Testament after works (destroyed 1945) by Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1804–1874), KPM, 1853–1855. Porcelain, height 54 inches.

Royal Porcelain from the Twinight Collection, 1800–1850, a collaboration between the Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation, Berlin and Brandenburg, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is on view at the Metropolitan Museum from September 16 to August 9, 2009. It is accompanied by a comprehensive catalogue by Samuel Wittwer and others, including Claudia Lehner-Jobst, published by Hirmer Verlag, Munich.

CLAUDIA LEHNER-JOBST, a freelance art historian specializing in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Vienna porcelain, is a guest curator at the Liechtenstein Museum in Vienna, where she was a co-curator of the showing of the Twinight Collection in 2007.