Notes on Photographs by Larry Silver, 1949–1955 at the New-York Historical Society.

Precisely because photography is thought to be the most objective of all mediums, it acquires over the course of years, and seemingly in spite of itself, a haunted quality that no other product of visual culture can claim to the same degree.

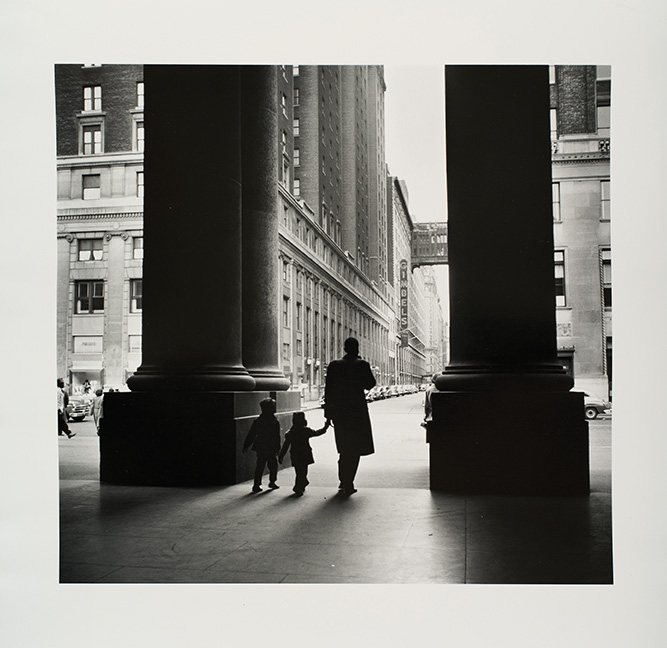

Fig. 9. Leaving Penn Station, 1952. Gelatin silver print 12 by 12 3/4 inches.

The forty-five photographs by Larry Silver that are now on view at the New-York Historical Society are a case in point. When Silver made these images between 1949 and 1955 he was a teenager. The last thing on his mind, one imagines, was to capture the mood or spirit or atmosphere of New York City in the immediate aftermath of World War II. Though beautiful, precocious, and often self-conscious works of art, these photographs seem to aspire to a no-nonsense objectivity fully in keeping with the spirit of the age, with its bullying virility, its pervasive slang, and its working-class mystique. We are in the age of Sinatra here rather than of Rudy Vallee.

Born in the Bronx in 1934, Larry Silver was mentored, while still in high school, by Lou Bernstein and other members of the so-called Photo League who frequented the Peerless Camera Store on East 44th Street. He won a scholarship to the Art Center School in Los Angeles, where he shot a distinguished series of photographs of the body builders along Santa Monica’s Muscle Beach. In 1959 he moved back to New York and established himself as a highly successful advertising photographer, whose clients have included American Express, IBM, and Procter & Gamble.

In the present exhibition, Silver documents New York City at a crucial instant in its evolution; it stood at the summit of its postwar triumph. In all but the most literal sense, New York was the capital of the United States at the moment when it became the most powerful nation in human history. To a greater degree than ever before or after, New York was the undisputed center of art and literature and music, of industry and leisure, of modernity itself. In one photograph children play beside a construction site that is on its way to becoming the United Nations (Fig. 1), the very embodiment of the postwar world. In another, we experience the quieter charms of New York, as two women rest beside the sparkling waters of the lake in Central Park. An image of Times Square, whose barrage of signage includes a multistory poster of Bette Davis in Dark Victory, beautifully depicts New York in its role as a center of popular culture (Fig. 4).

And yet, Silver also captures the moment when an influx of new and generally poorer immigrants fills the void left as the middle class begins its flight to suburbia. The sense of fraying around the edges, which would become unmistakable in the 1960s and 1970s, is already starting to appear in Silver’s photographs, even though the documentation of that process was never their ostensible point. As evidence of it we see, in one photograph, the trunk of a snazzy postwar convertible beside a row of tenement houses, with a long clothesline strung between them (Fig. 5). In another, a slumped-over wino hides his face from the sun, within sight of the Empire State Building. Elsewhere, a group of men-but no women-sit in a waiting room at Grand Central Terminal (Fig. 3), in their homburgs and the garrison hats of a nation still largely deployed (the compulsory draft continued until 1973).

A number of children populate the photographs of Larry Silver, who, at the time he took these pictures, was scarcely more than a child himself. We find them playing in the snow or standing amid the rushing waters of the Bronx River (Fig. 6). In one wintry street scene, a boy eats a treat (Fig. 8), while in another a baby in a carriage reaches out to pet a dog. But it is interesting and odd that few of these children seem to be having fun, or even to be having a happy childhood. Once again, that does not appear to be the intended point of these images: they reveal none of that subversive dismantling of childhood that Diane Arbus would make her dominant theme a few years later. Still, these children exhibit little of the joy that defines the children of André Kertész or Eugène Atget.

In part, that sense of heaviness and foreboding is attributable to the fact that all of Silver’s photographs are shot in rich, heavy black and white: color photography, although it existed at the time, was still considered an extraneous, even inartistic option for serious photographers. But even if color had been more prevalent, it would be hard to divorce these images, or the cultural moment they embody, from the largely binary equation of black and white that informs Silver’s artistic view of the world. The darkened pillars of the old Penn Station, opening eastward onto 32nd Street, are an especially masterful example of this (Fig. 9). Silver’s photographs recall film noir, which was a prominent part of the cinema of the day. When, early in her career, Cindy Sherman ironically reproduced film noir stills, she was implicitly commenting, from the safe distance of one human generation later, on the entire aesthetic project of Larry Silver and his contemporaries.

But today we see these images differently from their original viewers more than half a century ago and differently from the young Cindy Sherman, working twenty-five years later. An indefinable beauty and moodiness, which were rarely if ever intended by Silver, have taken over his photographs. Objectively, there is little that invites us to enter or inhabit them. Rather they almost seem determined to deflect any such ambition. But through a reflex of our natures, we humans cannot resist importing into these old photographs an almost mystical element that few viewers would have found in them only a generation ago. The mysterious alchemy of time and sentiment has finally transformed the dreary world that Larry Silver so skillfully photographed into a place of improbable enchantment.

Photographs by Larry Silver, 1949–1955 is on view at the New-York Historical Society until December 4.

Fig. 1. Children on United Nations Construction Pile by Larry Silver (1934–), 1951. Gelatin silver print, 14 3/8 by 13 5/8 inches. The photographs illustrated are in the New-York Historical Society, gift of William and Jeryl Silverstein.

Fig. 1. Children on United Nations Construction Pile by Larry Silver (1934–), 1951. Gelatin silver print, 14 3/8 by 13 5/8 inches. The photographs illustrated are in the New-York Historical Society, gift of William and Jeryl Silverstein. Fig. 2. Boy on Rooftop, 1951. Gelatin silver print, 12 1/8 by 13 3/4 inches.

Fig. 2. Boy on Rooftop, 1951. Gelatin silver print, 12 1/8 by 13 3/4 inches. Fig. 4. Times Square, 1952. Gelatin silver print, 16 5/8 by 13 5/8 inches.

Fig. 4. Times Square, 1952. Gelatin silver print, 16 5/8 by 13 5/8 inches. Fig. 3. Grand Central Terminal, 1952. Gelatin silver print, 13 1/4 by 13 inches.

Fig. 3. Grand Central Terminal, 1952. Gelatin silver print, 13 1/4 by 13 inches. Fig. 6. Raft, New York Botanical Garden, 1950. Gelatin silver print, 12 3/8 by 17 3/8 inches.

Fig. 6. Raft, New York Botanical Garden, 1950. Gelatin silver print, 12 3/8 by 17 3/8 inches. Fig. 7. Macy’s Parade, 1951. Gelatin silver print, 13 1/8 by 16 3/4 inches.

Fig. 7. Macy’s Parade, 1951. Gelatin silver print, 13 1/8 by 16 3/4 inches. Fig. 5. Manhattan Backyard, 1952. Gelatin silver print, 11 3/4 by 12 inches.

Fig. 5. Manhattan Backyard, 1952. Gelatin silver print, 11 3/4 by 12 inches. Fig. 8. Nearby Eggs, 1952. Gelatin silver print, 11 1/8 by 10 7/8 inches.

Fig. 8. Nearby Eggs, 1952. Gelatin silver print, 11 1/8 by 10 7/8 inches.