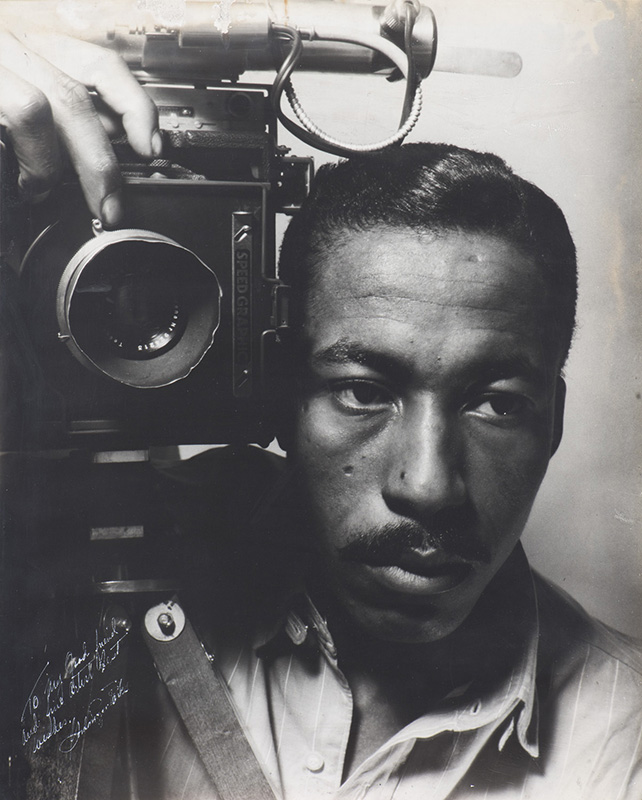

In the early part of his career, photographer Gordon Parks (1912–2006) honed his craft the way freelancers do: by taking any job he could get. He worked for a newspaper in St. Paul, Minnesota; did PR for Standard Oil; shot fashion for Ebony, Circuit’s Smart Woman, and Glamour—“everything that came along,” as he explained in a 1977 interview for Cinéaste magazine. “I knew that as a black photographer . . . I’d have to do more than just black subjects.”

Gordon Parks: The New Tide, Early Work 1940–1950, a traveling exhibition organized by the National Gallery of Art and the Gordon Parks Foundation, and currently at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas—the third stop on its tour—brings Parks’s formative years to life through some 150 photographs, as well as rare copies of magazines, newspapers, pamphlets, and books.

Parks was born in Kansas, where he grew up impoverished, one of fifteen children. By the time he was twenty he found himself in Minnesota, employed variously as a waiter, rail worker, bartender, and semi-professional basketball and football player. It wasn’t until 1938 that he discovered his calling, when he saw newsman Norman Alley’s photos of the Sino-Japanese War. “Suddenly this new medium seemed like a possibility to me . . . whereby I might be able to express myself,” he recalls in an interview recorded for the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art. He bought a 35mm Voigtländer and started shooting, training his lens on scenes of destitution and desperation surrounding him in St. Paul and Chicago during the Great Depression. After chancing upon the sharply-focused documentary photo work of Dorothea Lange and Arthur Rothstein, whose goals seemed similar to his own, Parks embarked for Washington, DC, where he apprenticed himself to Roy Emerson Stryker, head of the Historical Section at the Farm Security Administration.

It was the first time young Parks had been to the American South, and to get him up to speed Stryker sent him out into the city with orders to “try to get into this restaurant” or “go to this store,” anticipating Parks would be turned away. “When I came to Washington, I practically hated every white face that I saw because of what happened to me,” Parks admitted. Rather than rage, Parks channeled his frustration into pictures that spoke, such as his portraits of janitor Ella Watson standing in front of a flag in her place of employment, the US Capitol building; and of an anonymous middle-aged black woman, hands folded and eyes lowered, sitting quietly underneath a photo of FDR, which watches over the scene like a religious ikon.

Stryker made sure it wasn’t only distrust and animosity that Parks was encountering, and the photographer would take white subjects as well, usually workers: fishermen, stevedores, fire fighters, and their families. His Grain Boat taking on a load of wheat, Port Arthur, Ontario, Canada captures a decisive moment to make Cartier-Bresson proud. “Anyone who was, I thought, more or less getting a bad shake. I . . . had the instinct toward championing the cause,” he explained to the AAA, and it was by looking through the prism of labor and struggle that Parks was able to see—and, through his pictures, communicate—the existential kinship to be found between working-class people.

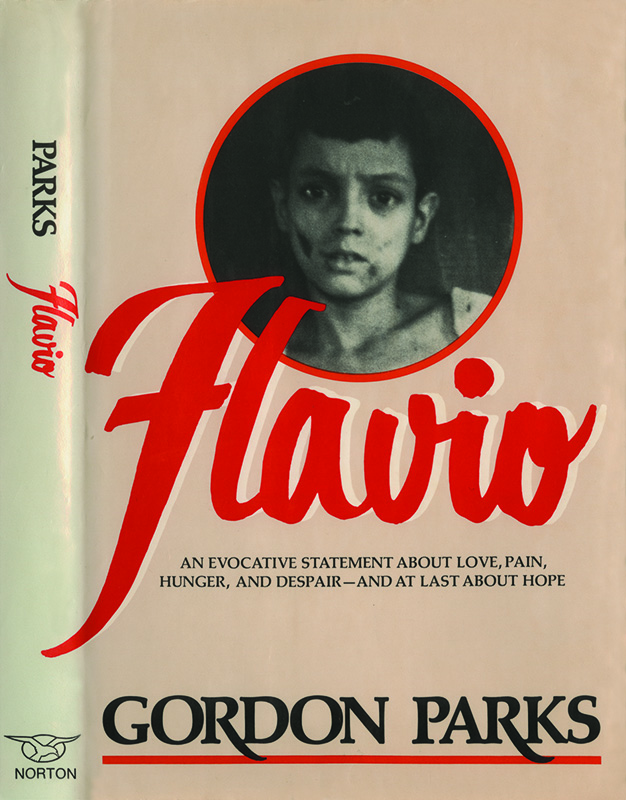

Parks’s compassionate bent and his brand of immediately-legible photo work was in demand by national publications such as Life, which hired him as its first black staff photographer in 1949, and for whom he would continue to document poverty in the US (as well as making forays into the beau monde, where he’d photograph figures like Duke Ellington and Muhammad Ali). On assignment in South America in the early sixties, Parks encountered a destitute and dirt-begrimed youth living in the slums of São Paolo named Flávio, who would become his most famous subject. Published as “Poverty: Freedom’s Fearful Foe” in Life’s June 1961 number, Parks’ affecting photos of the boy sparked an outpouring of sympathy from readers, and Flávio was whisked to the States to receive two years’ treatment for asthma. Brazilians, however, didn’t take kindly to Life’s exposé: the magazine O Cruzeiro sent its own photographer to New York City to document the less exotic poverty surrounding the magazine’s offices in Midtown Manhattan. Parks would make several return trips to Brazil to photograph Flávio as he grew up before the pair eventually fell out in the early nineties. The saga was chronicled in The Flávio Story, a book published last year by Steidl and the Parks Foundation, and is currently the subject of an exhibition at the Getty Center: Gordon Parks: The Flávio Story, which includes more than one hundred photos by Parks, Hikaru Iwasaki, and O Cruzeiro photographer Henri Ballot.