“It is believed that the most effectual means of preventing [tyranny] would be, to illuminate . . . the minds of the people at large,” wrote Jefferson in 1779. It was a message that the Greenbush Group certainly took to heart. A syndicate of engravers, printers, and publishers active in rural Vermont in the first half of the nineteenth century, the group’s maps, globes, prints, and Masonic miscellany is the subject of an exhibition closing this weekend at the Bennington Museum in Vermont.

James Wilson, the group’s leader, was the first globe maker in the New World. The story goes that Wilson saw an economic opportunity for making globes during a trip to Dartmouth College in 1796, and after teaching himself the tools of the trade, opened a globe-making factory in Albany in 1810. The 1831 New American Celestial Globe on view at the Bennington, which is replete with hand-colored engravings and a turned wood base and was intended for use by maritime navigators, was produced in that city with the assistance of Wilson’s sons. It was probably sold as one of a pair, the other likely being a terrestrial globe that would have drawn on Wilson’s prodigious knowledge of geography, a subject in a state of flux, as, with every mile the settlers advanced into North America, new features of the landscape would be discovered.

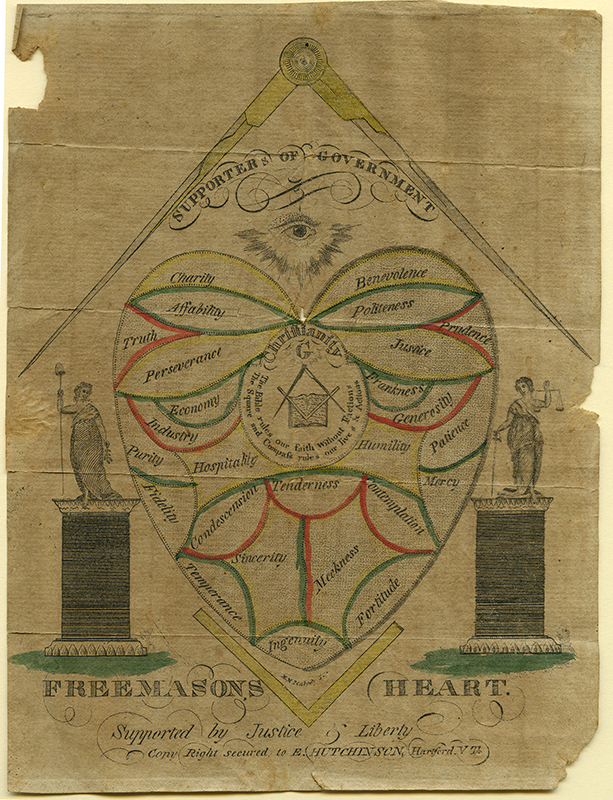

A number of maps engraved by Moody Morse Peabody of Hartford are on view as well, the product of a fruitful collaboration with the publisher Ebenezer Hutchinson. Both, likely, were Masons, a powerful sect in New England and the subject of much ire and suspicion. A silk apron and a paper “Freemason’s Heart” (a heart surrounded by Masonic symbols and slogans) with engravings by Peabody, produced by Hutchinson, testify to their dedication to the lodge, while a chapbook detailing a popular Mason conspiracy theory of about 1832, with engravings by Benjamin Tuel, illustrates opposition.

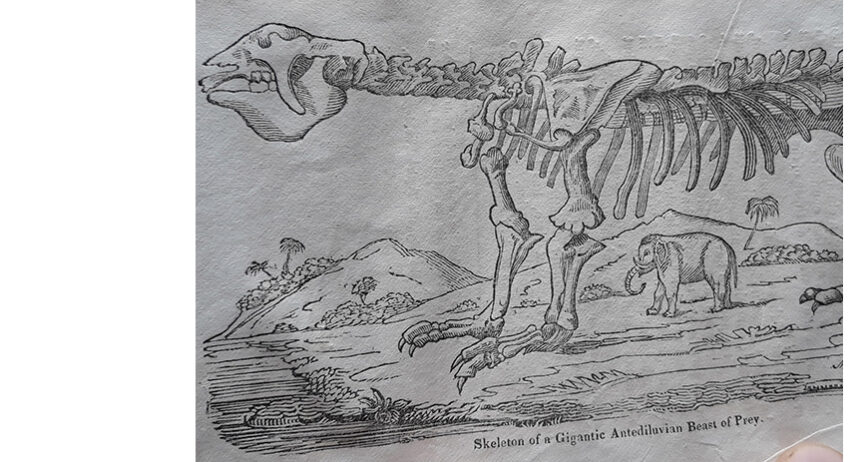

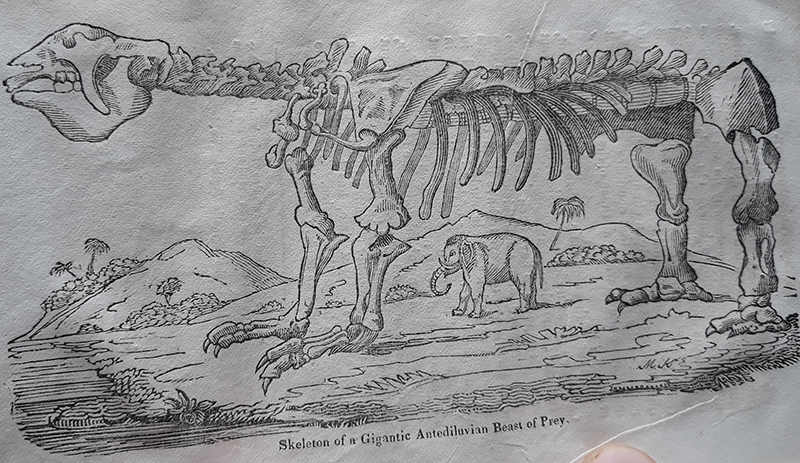

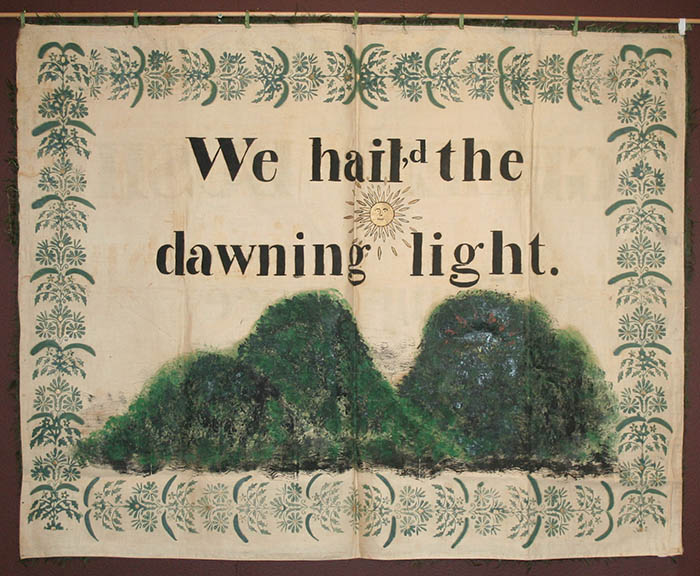

Plates from the first Vermont Bible by Isaac Eddy, believed to have possessed the first printing press in the Americas, are also on view, as is a print from the War of 1812 and another that depicts an early fossil find from the days when ancient mammals, not dinosaurs, fired the American imagination.

In the end, the conditions that gave rise to what scholar David Jaffee called “Village Enlightenment” were relatively brief, plowed under by the professionalization of scientific inquiry, as well as by the consolidation of media interests in the young republic’s urban centers, which latter development would do much to shape the intellectual conversation during the Civil War and in the succeeding century and a half since.

Village Enlightenment: Print Culture in Rural Vermont, 1810–1860 • Bennington Museum, Bennington, Vermont • to September 15 • benningtonmuseum.org